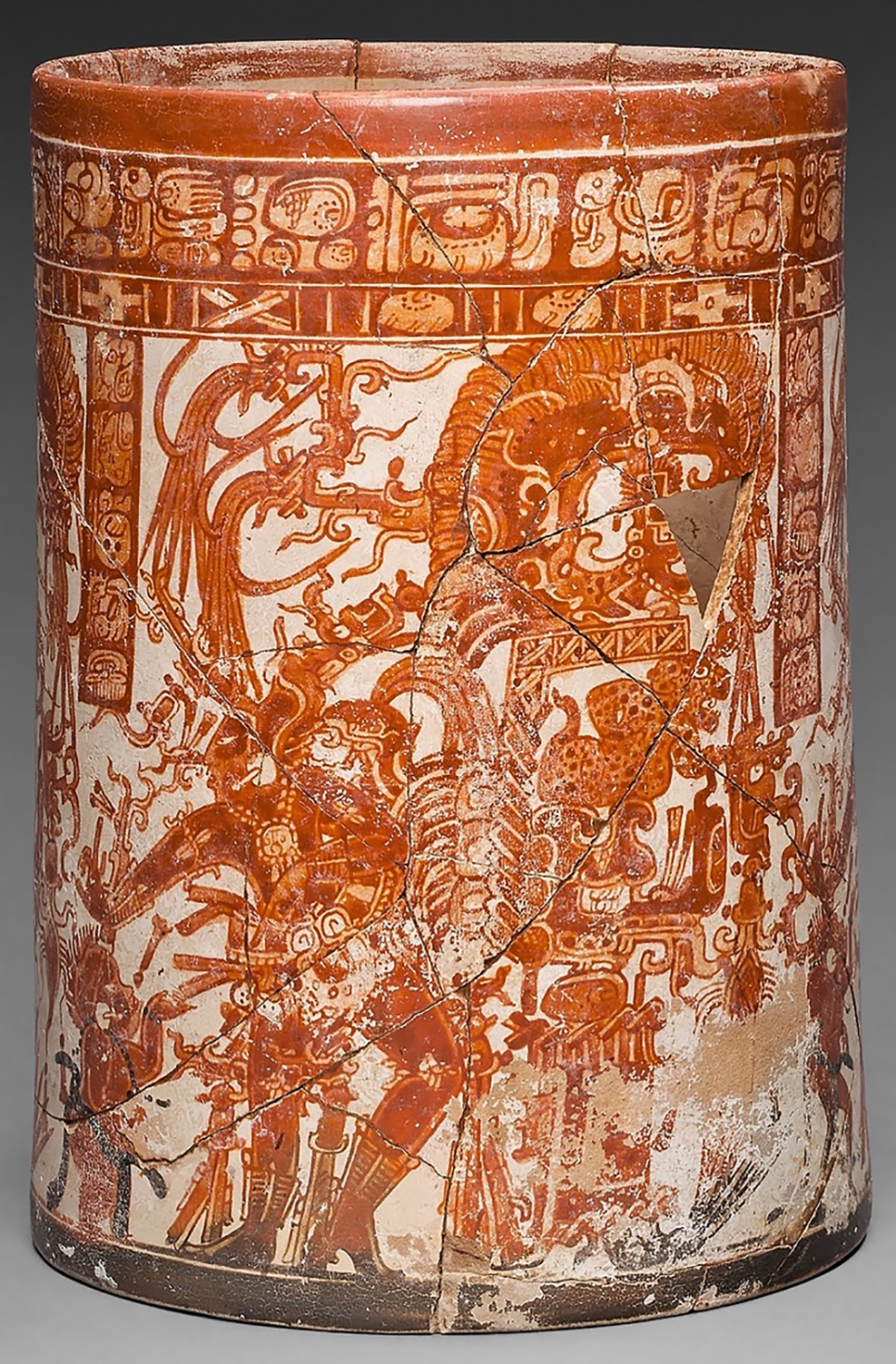

The Dancing Maize God

Vessel of the Dancing Lords (A.D. 750/800)

Photo courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago. Maya Image Archive

This vessel was produced in the Naranjo, Guatemala workshop for Lord K’ahk’ Ukalaw Chan Chaahk. At the top, above a band of symbols indicating the sky (a “sky band”), the hieroglyphs read: “His painting, (artist’s name?), artist sage, Lord Maxam, child of woman, Holy Lady Water-Venus, Lady Lord of Yaxhá (title?)(title?), child of man, Three Katun (60 year) Sacrificer, Lord Flint Face, Holy Lord of Naranjo, pure artisan.”

The Classic Period name of the youthful maize god depicted with a tonsure is not known for certain, but because it includes the number “One,” scholars have referred to him variously as Hunal’-Ye, “One Maize Revealed,” Hun Ixim “One Maize,” the creator deity, Hun Ajaw “One Lord” and “First Father.” Some scholars have suggested that he is the father of the Hero Twins, “One-Hunahpu,” in the Popol Vuh—the mythic story of the Quiché Maya. In the inscriptions, Nal is the hieroglyphic word for “maize.”

Frequently, as shown above, the tonsured maize god dances his descent into the underworld and subsequent resurrection that mimic the life cycle of the maize seed which is buried in the ground. Then, due to the action of his “sons” (all farmers) he rises from the dead and is revealed as a sprout.

Our word “mimic” does not convey what was going on in the minds of the ancient kings; we can only imagine. But it has been suggested that the kings who reenacted the dance of the maize god, likely under the influence of a hallucinogen, allowed their bodies to be inhabited by the ch’ulel “spirit” or “soul” of the deity. The depictions in Maya art are of the actual maize deity dancing, not the king. (This is what happens in Jaguar Sun. See the segment from my novel below).

As noted in the “Significance Of The Ancient Maya” link on the home page of this site, every detail of the ancient Maya world, at least for the elites, had cosmic associations. The above vase provides an excellent example of what the king looked like, what he wore and the elaborate regalia involved. Maya iconographers have deciphered the meaning of every element.

- The maize god’s tapered head and tonsure represent the form of a maize husk (precious sustenance) and tassel.

- Although the precise meaning of hand-gestures is not known, their frequent and consistent repetition in Maya art is a demonstration of their significance. Here, they are very specific. “Today’s Maya, who sign, use the same gesture for corn as did the ancients.” (Justin Kerr)

- The king is decked out in jade (“breath” “spirit”) jewels—beaded necklace, ear flares, bands on his upper arms and knees and beaded ankle and wrist bands.

- His headdress consists of iridescent quetzal feathers, the blue-green color symbolizing water, life and sky.

- His uplifted heel and the long outward ends of his loincloth indicate vigorous motion, replicating the stars that “dance” circles around the North Star—sometimes referred to as “Heart of Heaven.”

- The belt assembly consists of a large Spondylus (spiny oyster) shell with three stars on it indicating the constellation Orion, which marks the three cosmic hearthstones and the split (birthing) place in the mythic turtle shell from which the maize god arose, reborn from the underworld. The shape of the shell is a reference to Xoc, possibly the name of a kind of fish in the underworld. Shells were used to collect sacrificial blood, another allusion to rebirth.

- What looks to our modern eyes like a jumble of elements behind the dancer, are items of significance situated in a tall, very elaborate “backrack” attached to a waist-armature composed of interlacing elements. It’s worn to show that the dancer is actually the maize god, not just an impersonator. Each element of the backrack—faces, symbols, feathers, animal figures—reference cosmic events associated with the god after he was resurrected. Considering the weight and intricacy of the total costume, it’s likely that these elements were made of paper, palm fibers, light wood and fabrics painted with a thin plaster slip.

- The head of the long-nosed figure toward the bottom-right is a “Witz Monster,” the personification of a hill or mountain deity, identified as such by the cleft in his forehead and circular features that symbolize “stone.”

- The jaguar figure sitting atop the Witz Monster is a reference to “Waterlily Jaguar,” a transformer, indicating that the dancer has been transformed from a human being into the maize god.

- Above the horizontal band of five X’s in a frame indicating the “sky,” is a highly abstracted representation of a figure referred to by scholars as the “Principle Bird Deity.” On this vase, we’re looking at him from the back, indicated by the massive bundle of feathers at the top. His head, with a long, upward curling snout, is to the left. The feathers and scroll elements issuing from it represent the life force. In another post, I’ll talk about this vein mythic bird who proclaimed himself higher than the sun god because he dispensed the life force from Heart Of Heaven.

At the bottom of the vessel far left, there’s a figure of a dwarf. Often depicted on Maya vases, particularly alongside kings and the maize god, they were trusted companions. It has been suggested that they represent the stubby ear of corn that formed on the same stalk as the dominant ear. They are also seen as attendants to the king similar to pages, individuals chosen by the gods to manifest supernatural powers, leftovers from a previous creation and counselors. The line above his nose indicates speech. Dwarfs appear to have held high status at court.

The Dance Of The Maize God

Excerpt From Jaguar Sun (p. 284)

THE WIND THAT HAD RUSTLED THE FEATHERS ON headdresses throughout the day had calmed by nightfall. As we entered the Court Of Sacred Directions, Venerable Amaté pointed out that the twenty men standing with torches around the courtyard were the sons of ministers. I judged there to be another thirty people already seated on the steps. My host made it very clear—“Lord Yellow Fire Macaw K’awiil will not be imitating the dance of the maize god. He will be surrendering his body, allowing him to dance again his rising from the Underworld.”

The story preceding the maize god’s resurrection was well known. As Eyes told it, before the sun was, he lifted the sky off the water at a place called, “Raised Up Sky.” To bring order to the upper world once it was raised, he set three bright stones in the sky and connected them to the earth by establishing a great tree of stars. When this was done, he realized that he had weaknesses. To overcome them, he sacrificed himself and descended into Xibalba, the “Place of Fright.” Then, to defeat death, he ascended from the Underworld and released maize seeds—new life—from Sustenance Mountain. From the maize, which grew in great abundance, First Mother fashioned a dough and with it made the first human beings. It was why foreigners spoke of us as “maize people.”

While we were waiting for the dance to begin, Venerable Amaté told me about the shrines that encompassed the courtyard, saying they were built in accordance with the ordering of the world directions—a red-painted House of the Sun on the eastern side where the sun is born, a black House of the Ancestors on the western side where the sun goes to die, a yellow House of the Underworld on the southern side and the tallest, a white-painted House of Raised Up Sky on the northern side to our left.

He explained that about forty paces in front of us, the long platform made of lashed bamboo was, for the dance, the Underworld place called Seven Water. A blue covering with white-painted waves, waterlilies and fish made it clear that this was a watery world. Painted in the center of the great cloth, I recognized Xoc, the monstrous fish-serpent who, according to the story, aided the maize god’s rebirth.

I wasn’t the only one growing impatient. “They cannot begin until the maize god fully enters Our Bounty,” my host said. “His wife offers him the sacred brew and watches until his eyes are no longer his own.”

“What brew? Do you know what it is?”

“Chih, but with the sap of the sacred buffo stirred in. Different frogs are more or less potent, so she has to keep giving it until his ch’ulel has gone wandering. Only then can the ch’ulel of Juun Ixim enter.”

“Where does his ch’ulel go?”

“Some say it treads the path of the Upperworld. No one knows. When Our Bounty returns, he has no memory of the dance or where he went during it. He describes it as a shimmering place with brightly colored serpents and other animals.”

A DEEP-VOICED DRUM ANNOUNCED THE APPEARANCE OF a dwarf who, according to Eyes In The Sky, stood for the stunted ear of maize on many plants. This man wore a black hip cloth painted with yellow maize kernels, a yellow K’uhuuntak headdress pointed back and a shell pendant.

The Hero Twins followed behind him, walking toe first, with blowguns leaning against their shoulders. I recognized One Lord because he had black spots on his red-painted body. First Jaguar wore patches of jaguar pelt on his arms and legs. Next, I expected to see Yellow Fire come out dressed as the maize god. Instead, to the sound of a somber flute and a slow drum beat, the god himself entered just twenty paces from where we sat. “Ayaahh!” I whispered. He bore so little resemblance to my friend, the sight of him startled me.

His head was drastically tapered, elongated and bald except for a yellow tassel tied high and hanging down the back. His skin color was lighter, painted, and he was naked except for a roll of twisted green cloth between his loins and drawn up to his waist. He even walked differently—more erect, also toes first. When he stopped, the drumming and flute playing stopped.

Suddenly, one drum pounded again, hard and fast. Chaak, the bulbous-nosed, serpent-legged lightning and rain god, came bounding into the courtyard, leaping and pounding his feet. Brandishing a long-handled axe and bent forward, he danced on his toes with alternating knee lifts. His bead-and-shell necklace clanked as he performed his well known swinging and chopping movements. I recognized the long black bag strung across his shoulder as containing rain.

The dwarf came to the front and gestured for us to sit. Avoiding the rain god’s swinging axe, First Jaguar approached, the drum went silent and he called out. “To atone for his weaknesses, Juun Ixim offers his body and blood.”

One Lord came and stood beside his brother. “By sacrificing himself, he chooses to overcome three weaknesses. First, he is all good; there is only good in his being. To be a complete god there must be evil as well. Second, he believes he will live forever. Finally, there is fear in him—he is afraid of death.”

The twin gods parted and the maize god came forward. His wide eyes stared straight ahead as if he were looking through us. Chaak came and stood in front of him, not breaking his gaze. The maize god bowed low and stayed bent at the waist, while Chaak rose, spun around and swung the huge shiny axe high, bringing it down on the maize god’s neck. Somehow, as the twins danced in front of them, the bloody head of the maize god fell and rolled across the pavement. And now the black water bag was on the fallen body, covering the place where the head had been.

Four men wearing black paint head-to-toe brought out a litter with a covering on it painted to look like a canoe. When they set it down, One Lord and First Jaguar lifted the lifeless body onto it. The painted men lifted it, and to the pounding of the drum, went forward with the twin gods paddling. Slowly, the bow of the “boat” tilted down to make its descent. With solemn footsteps, the canoe bearing the body of the maize god circled the courtyard and set the litter down in front of the watery Underworld. Behind it, was the face of the Xoc serpent.

With the dwarf swinging a ceramic censer over the body, the twins lifted it onto the platform and covered it with a black cloth. One Lord came before us again, to say the maize god’s body was being re-established by Xoc and the other fish. As he told about the fish-serpent, his brother danced the reconstitution rites in front of the altar with his arms upraised, hips swaying and toe-heel steps matched to heartbeats on the drum. Lub-dum, lub-dum. Behind him, the black cloth began to move. Slowly, the maize god pulled the cloth aside and sat up. I whispered to Venerable Amaté that, at Calakmul, the tellers said it was the twins, not Xoc, who restored his body.

With the dwarf guiding him, the maize god moved to the front of the watery Underworld. There, he was met by three young women, goddesses, naked except for red-painted arms and shoulders, pearl wristlets, jade ear ornaments and green waterlily headdresses. Two of the goddesses held out regalia items for the dwarf to cense. The third presented the items one at a time for the maize god’s appreciation and acceptance—by holding them up to his eyes, while averting hers. Pink anklets of thin shell-tubes came first. Then, attesting to his rebirth, they tied on the belt that had sky signs around it. And from it, a thick twisted cord hung over a white shell bearing the painted face of the Xoc fish.

Jewels came next—jade earflares and a necklace of jade beads surrounding a god-face medallion. Pearls sewn onto white sacrificial cloths were tied around his upper arms and then he bowed to receive a tall headdress of white flowers in front, with twisted and oversized maize leaves in back.

Fully gowned, and gloriously adorned, the maize god expressed gratitude to the goddesses by facing the palm of one hand to them, while receiving the blessings from above with the other.

I wondered, What about the skirt? In other places the story had him wearing a skirt made of jade tubes and beads in the form of an open net—like those on turtle’s carapace. Even the lords on monuments were shown wearing the beaded skirt.

The dwarf escorted the maize god to the canoe again. Now, the twins turned and paddled with the bow rising. The dwarf followed, beating a turtle shell with an antler to call back the god of lightning and rain. While we were watching, another man painted black ran out, pulled the Underworld cloth off the platform and ran back. Six others clad in black paint with green leaves, twigs and vine carried out an enormous turtle shell, taller than a man and three times as long with the net pattern painted on its back. While they took it up the steps and set it on the platform, four more men painted black brought out torches and took positions alongside and in front of Great Turtle—the world.

The tellers at Naachtun said the world was a bony skull. At Cancuen they said it was a crocodile.

The tree drum pounded. Boom!—Boom! Another joined it. Boom!!—Boom!! Boom!! And then a third: BOOM!—BOOM! BOOM! Faster and pounding hard, the drums brought back Chaak who spun and swung his axe, dancing toes-first with knee lifts. I was so intent on the dance I didn’t notice that the canoe had disappeared into the darkness.

The twin gods came before us again, now with seed bags strung across their shoulders. When the drumming stopped, they raised their arms in a gesture that invited us to stand and recite the words we’d learned as sprouts and flowers.

All is still, silent and calm. Hushed and empty is the womb of the sky. There is not yet one person, one animal, bird, fish, tree, rock or forest. All alone is the sky. The face of the earth has not yet appeared. Alone lies the expanse of the sea, along with the womb of the sky. There is not yet anything gathered together. All is at rest. Nothing stirs. All is calm, at rest in the sky. There is not yet anything standing erect. Only the expanse of the water, only the quiet sea. There is not yet anything that might exist. All lies calm and silent in the darkness of the night.

After a moment of silence, there came a sound of knocking on wood. Chaak tilted his head and put a hand to his ear. The sound came again, louder. With the dwarf marking his steps on the carapace drum, the lightning lord approached the platform and went up the steps. Standing behind Great Turtle, he listened again. And then he spoke. “How shall it be sown? Who will be the Provider? Who will be the Sustainer? Let it be so. Let it be known. Let it be seen.”

To a flurry of drumming, Chaak gripped the handle of his axe with both hands, swung the head forward making it look heavy. Swinging it back and high, he brought it down with a single hard pounding of all the drums. After that, except for the fluttering of torches, silence.

The sacred moment had arrived. I held my breath. And then it came—the sound of a crack. Then another, louder. The bearers in black leaned their torches toward Great Turtle. Another loud crack and the shell broke open. Chaak stood back with his palms facing the turtle, the sign of wonder and glory. First to rise out of the split shell were green maize leaves, then feathers and a headdress with yellow tassels. Beneath it, was the face of the maize god. Again, he seemed to be looking through us rather than at us. One Lord offered the seed bag to him, and he took a handful of seeds. Standing up to his knees in the crack, he turned and scattered the seeds to the four directions.

At Waka’, the tellers said he rose from a split in a mountain. At Xultun they said it was the back of a peccary. So many differences.

The twins helped the maize god step out of the carapace. When he came down and his feet touched the floor a flute sounded and he began a joyful toe-heel dance with graceful arm movements, turning, taking more seeds from the bag, casting them to the four directions.

With the dance completed and the dwarf drumming on his carapace shell, the dancers followed the maize god across the courtyard to House of Raised Up Sky. There, inside the shrine, according to Venerable Amaté, Yellow Fire’s wife would present him with the offering bowl containing the sacred bloodletter. Venerable Amaté said he preferred a stingray spine.

WALKING BACK TO THE LODGE WITH MY BROTHERS, I mentioned some of the differences in The Dance of The Maize god story as it was told from place to place. “Just like us,” Venerable Amaté said, “the gods reveal themselves in different ways at different times and in different places.”

“Are you saying the stories can all be true?”

Venerable Toucan dropped back so he could see my face by the light of his torch. “It is the truth of the story that matters, what it says beyond what the tellers say about the gods—how they look and what they wear.”

“Even if I was authorized,” I said. “I would not tell god stories. I cannot know which of them is true.”

Venerable Amaté’s face flickered in the orange light. “Our Bounty is not a member of the brotherhood, but he took the vow of truth. Had he not believed the story of the maize god as it is told and danced here, he could not have surrendered his body to him.”

“If I were on your path,” Venerable Toucan said, “I would not want to be authorized. The gods are spirits. No one can say what they are like. Like rain falling on the hand, we cannot hold their descriptions. But we can and should grasp the truth of their stories—the lessons they provide.”

“I have heard so many different voices on this, I do not know what to believe,” I said.

“What do your ancestors say?” Venerable Amaté asked.

“They were warriors, they have not guided me very well. I do not trust them.”

“Trust your ch’ulel, Wakah. That is where pure truth resides.”

____________________________________________________________________________

For a brief description of The Path Of The Jaguar novels: Go to the Home Page—Novels

Links To Amazon.com for paperback books and Kindle Editions

Jaguar Rising: A novel of the Preclassic Maya