Ancient Maya Ancestor Veneration

The continuation of wisdom and support

The old men used to say that when men died, they didn’t perish, they once again began to live. . . They turned into spirits or gods. — Alfred Tozzer, American anthropologist

This is likely a noble ancestor depicted on the frieze of a council house at Copan, Honduras.

Among the ancient Maya, evidence of ancestor veneration shows up around the first century B.C. At that time, decisions were being made about the inheritance of land use. Land was not owned, but the right to use it was handed down. The principle of first occupancy gave preferential access to a man’s descendants because his house was built over his deceased ancestors who came to be regarded as guardians of the house and proximate fields and forests. When the ancestor was the founder of a lineage and a pyramid-temple was of raised on the site, it would be called his nah “house.” And the entire site would be considered “the home of…”

Ancestor veneration ultimately is not about the dead, but about how the living make use of the dead; it’s a type of active discourse with the past and future, embodying the centrality of Maya understanding of death and rebirth.

Mark Wright, Anthropologist

While ancestor veneration provided the rules of inheritance, it often created conflict between household heads and their heirs. Maya anthropologists observe that ancestor veneration promotes and perpetuates inequality and alienation from resources within the household as well as the polity. In times of hostility, the tombs of royal ancestors were plundered. Naranjo Stela 23 (Guatemala) records the desecration of the tomb of a Yaxha Lord.

Kings often venerated their ancestors by having their heads float above them on monuments, facing down at the top of the composition. Piedras Negras Stela 5 shows the king’s ancestor beneath the Principal Bird Deity at the top. The Maya regarded the human head as the place from which breath, the vital force, emanates. A Maya text confirms this —

Each ancestor guards the boundaries of his land. When the spirit leaves (the body), the head goes with the spirit, just down to his shoulders. His strength and his head and his heart go wherever they want to. The head and face confer honor as well as being honored.

In the Classic Period, ancestor veneration was politicized, used to sanction elite power and authority. Kings would enter their ancestor’s burial vault and perform ceremonies involving fire and the sprinkling of blood and incense. This is depicted on Piedras Negras Stela 40 and Tikal Alter 5.

In some places the kings deified their ancestors. This, of course, meant they inherited divine blood. And it put them on a trajectory toward becoming deified after death. Further, a king could make the case to his royal household that his ancestors—and later themselves—would protect them and guard them against usurpers when “they took the dark road.” Died. When several generations of ancestors were buried in the same location, a pyramid-shrine could be built over it, and continuously expanded. This made the place sacred, in some cases a pilgrimage destination.

Idols of the apotheosized ancestors were often the recipients of sacrificial offerings. Made of wood and painted blue, these figures were heirlooms that were passed down through the generations. Spanish chronicles indicate that these idols were carved during the Maya month of Mol’ and the preferred wood was cedar.

They made wooden statues and left the back of the head hollow, then burned part of the ancestor’s body and placed the ashes in it and plugged it up… kept in their houses… great veneration… made offerings to them so they’d have food in the other life.

Frey Diego de Landa, Spanish priest

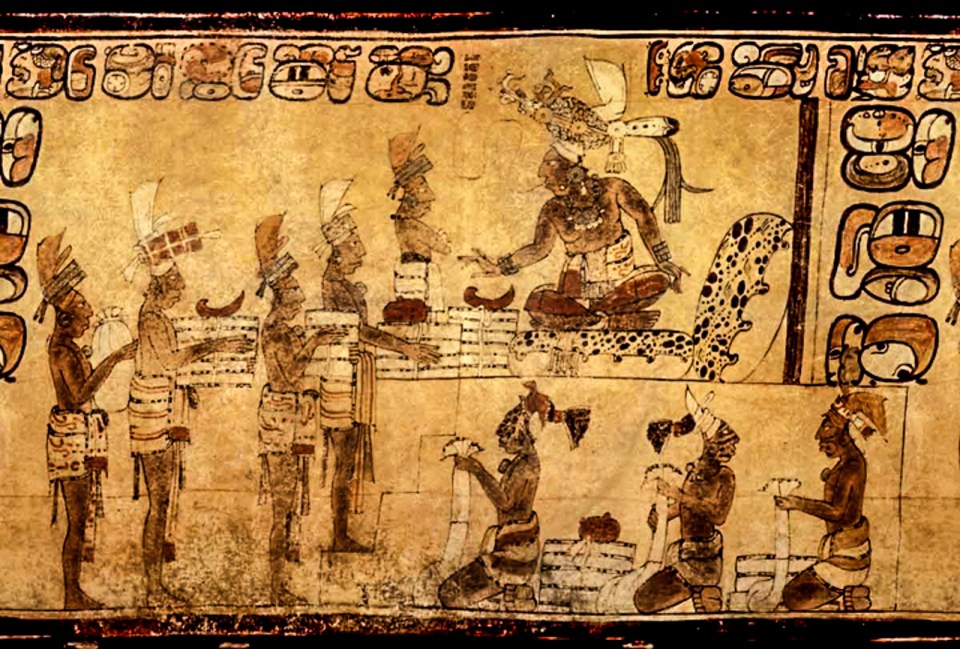

Not all dead relatives were venerated, only lineage heads and people of position. Their remains were treated preferentially. Both men and women were candidates for ancestor status. Because the bones of deified ancestors were sacred, they were kept in bundles with other sacred objects. Considered relics that contained power, these objects frequently appear beside kings seated on thrones depicted on painted vases.

Vase rollout photo courtesy of Justin Kerr

Here, the bundle containing ancestor relics sits on the throne behind the king, under the feathers being presented to him. Below the throne is a vase containing tamales dripping with sauce, perhaps chocolate.

Maya iconographer Carl Taube observed that “Only kings or other high nobles could look forward to resurrection and a return to this diurnal paradise and dwelling place of the gods and euhemerized ancestors, called Flower World or Flower Mountain. Flower Mountain is depicted in Maya art not only as the desired destination after a ruler‘s death, where he would be deified as the Sun God, but also as the paradisiacal place of creation and origin. Evidence for the belief in Flower Mountain dates to the Middle Formative Olmec (900-400 B.C.) and is also attested to among the Late Preclassic and Classic Maya as well, from about 300 B.C. – A.D. 900.”

Maya communities today maintain lineage shrines that go back many generations.

The source for much of this information is A Study of Classic Maya Rulership by anthropologist Mark Wright’s 2011 Dissertation.

A Healer’s Advice: Gather Your Ancestors Around You

Excerpt From Jaguar Wind and Waves (p. 141-142)

Whenever your husband—or anyone else—says or does something that ruffles your leaves, stand tall and watch. Let it blow past you. The amaté neither blames nor scolds the wind. It thinks not of lashing back. It knows it has deep roots. It trust that it will hold.”

“By roots you mean my ancestors?”

She nodded. “Call out to them by name. Ask them for strength when the winds blow strong, when the waves threated to drown the real you. You were brought up trusting and revering your ancestors, were you not?”

“I was. But I was also taught to speak up, not let a man treat me like a dog.”

“The greater part of standing and watching is knowing who you are and what you stand for. The warrior has his shield, the turtle has its shell, the house has its roof. Human beings hold to the truth of who they are in order not to be crushed.”

“I have become so busy with the household, my children, and my husband’s torments, I have lost the truth of who I am. That is what I want back. So whatever he says or does, you want me to just stand and watch? Say nothing? Do nothing?”

Lady White Gourd nodded. “For now, until your flower is whole again. When he sings a song or dances a dance that offends you, stay steady inside yourself. Allow it and listen. You do not have to be offended or hurt by anyone. Choose not to be hurt. Let the winds blow past. Offer no resistance. Just stand firm. Remember your roots and say to yourself: ‘stop, drop and endure.’ No resistance, not even in thought. Put away the part of you that wants to resist. And let the wind and wave pass. Then, as quickly as possible, remove yourself to a quiet place where you can be alone. Gather your ancestors around you like a blanket, and offer words of gratitude for what they have given you. Name it—what you received from them. And ask them to calm the storm.”

____________________________________________________________________________

For a brief description of The Path Of The Jaguar novels: Go to the Home Page—Novels

Links To Amazon.com for paperback novels and Kindle Editions

Jaguar Rising: A novel of the Preclassic Maya

Jaguar Wind And Waves: A novel of the Early Classic Maya

Jaguar Sun: The Journey of an Ancient Maya Storyteller

___________________________________________________________________________

My other sites—

Love And Light greetings.com: A twice-weekly blog featuring wisdom quotes and perspectives in science and spirituality intended to inspire and empower

David L. Smith Photography Portfolio.com: Black and white and color photography

Contemplative Photography: A weekly blog where a fine-art photograph evokes a contemplation

Ancient Maya Water Management Systems

The rise and fall of intensive agriculture in the Maya area

In this model of central Tikal, Guatemala the dark-colored basins indicate the location of large, very deep reservoirs. The entire city was built with slopes so the runoff would fill them during the rainy season, and these sustained the city all year long.

Around 2000 BCE, much of the Central Lowlands of the Yucatan peninsula consisted of year-round wetlands (bajos or swamps). The rainy season usually insured the swamps would be inundated, but during the dry season they dried up and solidified like concrete. Agriculture was only possible January through February and again May through June when enough rain fell to soften the clays without completely flooding them. Year after year, a major challenge for the kings and calendar priests was to manage the alternating lack of water and its abundance within the same area by appealing to chaak, the god rain and thunder.

To the north there were cenotés, large collapsed limestone depressions or sinkholes that contained ground water. There were no rivers or lakes in the central lowlands because the limestone bedrock completely absorbed the rainfall. East to Belize and to the south, there were some rivers and shallow lakes fringed with waterlilies, cattails and grasslands.

In the lowland heartland, the Maya planted two crops during the rainy season on elevated ridges. In the dry season they cut canals through them to speed the drainage of the rainy season’s floods, allowing for earlier planting at the beginning of the dry season and extending it long enough to harvest two dry season crops.

Beginning around 100 CE, most of the surface water in the swamps disappeared. Several feet below them is a layer of what was once moist wetland peat, rich with pollen from trees, aquatic plants and maize. At the end of the Preclassic (around 300 CE) and for the next 500 years, the soil was buried in successive layers of waterborne limestone clay. As the population grew, slash & burn farming—burning trees to make fields for crops—decimated the forest. With the trees gone, the rain washed away the soil, and the limestone beneath it eroded to powder which ran downhill filling the swamps with fine-grained clay.

By 250 CE (Late Preclassic), the bajos silted up and the surrounding wetlands were gone. For five months of the year, water was scarce. Nakbe and El Mirador, two of the earliest and largest cities the Maya ever built were abandoned. Water collection became paramount. Pyramid temples, shrines, palaces, platforms, plazas, stairways and roads were constructed so runoff from the rains would empty into to reservoirs. At Tikal they dug 10 reservoirs with a 40-million-gallon capacity and sealed them with black clays from a swamp east of the site.

The making of plaster, mortar and stucco to pave plazas and coat buildings—to make them smooth and gleaming white in the sunlight—required the felling of trees to burn limestone. To create a lime kiln, they stacked logs about 5 ft. high in a circle, leaving a 1 ft. wide hole in the center. On top, they heaped a layer of crushed limestone about 30 inches high. Then they dropped leaves and rotten wood into the center hole and set it on fire. The kilms burned for about 36 hours, from the bottom up and inside out. What remained was a pile of powdered quicklime.

When the builders were ready to plaster, the powder was mixed with water and thickened. As it dried on a surface, it became calcium carbonate, which made a hard, smooth, bright white and long-lasting plaster. In places, paved steps, courtyards and plazas were 3 1/2 ft. thick. Esteemed Maya scholar, Michael Coe, cites the production of plaster as a primary reason why the lowland forests were depleted by Late Classic times.

The Maya farmed the remaining shallow swamps by cutting irrigation ditches into the limestone clay and building up mounds beside them for planting. Many of the lowland cities were built on islands in these swamps. A variety of hydraulic systems were employed, different at different places and times. These included—

- Mucking. Nutrient rich muck from the swamps was hauled out in back-baskets and dumped on fields to create topsoil.

- Agua Culture. Ponds in Belize and shallow reservoirs in other places were dug to cultivate lily pads. These provided an ideal habitat for fish, and the pads were used for mulch.

- Hillslope Terracing. Rock walls were built horizontally and stacked vertically to contain crops and take advantage of natural watering. In the highlands entire hills and mountains were terraced.

- Canals. These were cut to create irrigation features and raised fields that could be farmed seasonally or year-round. Evidence of the earliest canal (between 200 BCE and 50 CE) encircles Cerros in Belize like a necklace. It was 20 ft. wide and more than 7 ft. deep, ideal for canoe traffic. At Edzna, on the coastal plain of Campeche, Mexico, among her 21 canals, one of them is 10 miles long, with a moat 300 ft. across. The soil and limestone taken from the moat were used to build the ceremonial complex. It’s estimated that the canal and moat took 1.7 million worker days.

- Chultuns. In outlying communities, caverns were dug into the limestone and lined with clay to hold large amounts of water. They served as wells during the dry season. In the large cities, chultuns were also used for dry storage.

- Springs, Wells and Waterholes. These occurred in the Guatemalan highlands. They were considered sacred, so ceremonies and rituals were held there, and ancestral gods held council at them—to review their descendant’s affairs. At Dzibilchaltun in Northern Yucatan, there were over 100 small wells.

- Raised Fields. These were created by digging a wide path through a swamp and depositing the muck on both sides to create long strips of dry land that were cultivated. Hundreds of people worked the raised fields year-round. These are seen today at Xochimilco not far from Mexico City.

Researchers claim that intensive agriculture resulted in three times the harvest of maize fields, allowing the population to double. Then it doubled again. Water management systems were very successful—for a while. But by the Late Classic (750 CE), the Central Lowland ecosystem’s carrying capacity had been reached. Malnutrition set in—indicated by a sharp decline in the stature of elites. Warfare increased, polities became fractured and there were severe, long-lasting droughts.

By 800 CE, people were losing faith in their ruler’s ability to garner favors from the gods—especially to produce the right amount of rain at the right time. As conditions worsened, people moved away. The reason for the “collapse” of Maya Civilization is still debated/ Certainly, there were many factors. And it was a gradual, century-long process. The timing and management of rain was certainly a prime contributor.

My sources:

Much of the information on ancient Maya water management systems came from publications by Nicholas Dunning and Vernon Scarborough, particularly the latter’s book The Flow of Power: Ancient Water Systems and Landscapes, and his Water Management in the Southern Maya Lowlands: An accretive model for the engineered landscape, an article published in Research in Economic Anthropology. More on the ideological side, I recommend Precolumbian Water Management: Ideology, Ritual and Power by Lisa Lucero and Barbara Fash.

Making Plaster from Burnt Lime Powder

Excerpt from Jaguar Rising (p. 132-135)

WHILE WE WERE TALKING, BARE-BREASTED AND BAREFOOT female slaves started coming onto the platform. Stone Face went to show them where he wanted their water jugs, and I followed. Behind them, male slaves carrying lime powder were coming up, some of them bent so low they had to lift their chins to avoid bumping into the step above them. Walks relieved the first man of his jar and poured a ring of powder five strides across between the edge of the platform and the line that marked the eastern wall. His apprentices, wearing damp cloths over their noses, emptied the other jars around the circle and continued to build it until the wall of powder came up to their knees.

True to his name, Walks In Stonewater stepped into the center of the ring and, as Stone Face poured in water, he began his “paddle dance.” At first, the powder just clumped like dough balls. More water made the clumps melt and even more brought bubbles and heat. The spreading, clumping and mixing continued until the mixture became so hot Walks had to jump out and stick his feet in a water bucket. Meanwhile, Stone Face had taken over the stirring with a canoe paddle, pushing dry powder to the wet center and vigorously twisting, pushing and pulling the clumps until they formed a smooth slurry.

Walks took another paddle and they worked the mortar until he tired and handed off his paddle to an apprentice. Three of them eventually formed a thick mound of slurry with a flat top. As the mixture approached the consistency that Walks wanted, he went around scooping it up with his paddle, lifting it and dumping it over and telling the apprentices how much more water and powder to add.

A burst of applause and yelps coming from behind the platform drew White Cord and me to go and look. Six white-robed bearers were carrying a mahogany platform into the plaza. On it was a tall red plaster model of the new temple. When it reached the center, Laughing Falcon raised his arms to quiet the crowd. Unfortunately, he was too far away to hear what he was saying.

White Cord speculated. “He is probably telling them how necessary the temple will be to the prosperity of the caah.”

Stone Face came to take a quick look, holding his paddle aside. “It is necessary—how else could he convince his father to come here?” I was tempted to repeat what Thunder Flute had told me about Laughing Falcon wanting to best his brother so he could inherit the throne at Mirador, but decided against it.

With the underlord’s speech ended, the drummers started again and Walks called to me. “Seven Maize! Do you want to see this or not?” I ran over and sat cross-legged beside the apprentices as their master took a fistful of the white slurry and opened his hand in front of us. “See how it does not run between my fingers?” He turned his hand over and it didn’t fall. “If it falls, it is too wet. If you wipe it off your hand and it leaves powder it is too dry. Mortar takes less water and three times more clay than plaster or stucco.” Beside him were two wide mouth ceramic jars. He dipped into the brown one with a small calabash and passed it around so we could dip a finger into the thick yellow ooze. “Smell it,” he said.

“Tree sap,” an apprentice said.

“Holol,” Walks specified. “It slows the hardening. You shred holol bark and pack it tight in a jar. Pour in limewater and let it sit overnight. The next morning you dig it out with a stick and press it through a fine weave basket.”

Stone Face took his paddle and made swirls along the outer rim of the slurry. Walks held the jar over the paddle and slowly began pouring the sticky substance onto it. “Never pour the holol onto standing slurry. It clumps and you get bubbles. And only use one jar for every two jars of powder. No more, no less. This is why we use the same containers and count the jars.”

The younger of the three apprentices asked the reason for slowing the hardening. “Obviously, so we can work it longer,” Walks said impatiently. “If it hardens before we take it to the blocks or while they are being set, it will not hold up. Slow drying mortar lets a block find its proper seating. When it takes comfort in the mortar, it makes a strong and lasting bond.”

Stone Face stopped his stirring and his brother took a handful of fine gray ash from the black jar. Bending down he went around the ring scattering the ash, keeping his hand close to the surface so the wind wouldn’t blow it away. Just watching him made me want to dig my hands into the jar. It seemed so soft. “It may not look like it, but ash is a thickener,” Walks said. “If we were making plaster, we would use less. Stucco, none at all. Since this is going to be mortar and needs to support weight, I will use all of it.”

“With respect,” another apprentice asked, “where do we get the ash?”

“Now that is a worthy question. Always and only from a lime kiln—”

“From the burnt wood, not the limestone,” Stone Face interjected.

“Never from a hearth or brazier. Holy men sometimes want us to use the ash from their censers. Some builders will do it. They say it makes no difference. Maybe not to them, but it does to me. I want my ash to come from the hottest fire possible—so it is clean and fine as dust. Look here—.” Walks held out his hand to show us the fineness of the ash. And when he blew it away there was not even a speck left on his hand. As he scattered the ash and Stone Face folded it in, the mound of white slurry began to turn gray.

Lord K’in was nearing his descent over the western trees and the plaza was emptying out. Laughing Falcon had gone, but there were still men waiting to receive their obligation. Determined to set the first course of blocks before it got dark, White Cord and Walks had the apprentices and me carrying jars of mortar and cloths in buckets of water as needed. Teasing me as he often did, Stone Face said I was too clean compared to the apprentices, so he chased me around the platform, pulled me down and wrestled with me until I was thoroughly coated with powder and plaster dust. As this was going on a lime bearer had come up and told White Cord that White Grandfather was asking for me. Stone Face and I were out of breath, panting when he told us. I was disappointed to leave because Walks said he would let me try my hand at laying some mortar.

____________________________________________________________________________

For a brief description of The Path Of The Jaguar novels: Go to the Home Page—Novels

Links To Amazon.com for paperback books and Kindle Editions

Jaguar Rising: A novel of the Preclassic Maya

Ancient Maya Thrones

The seat of divine power and influence

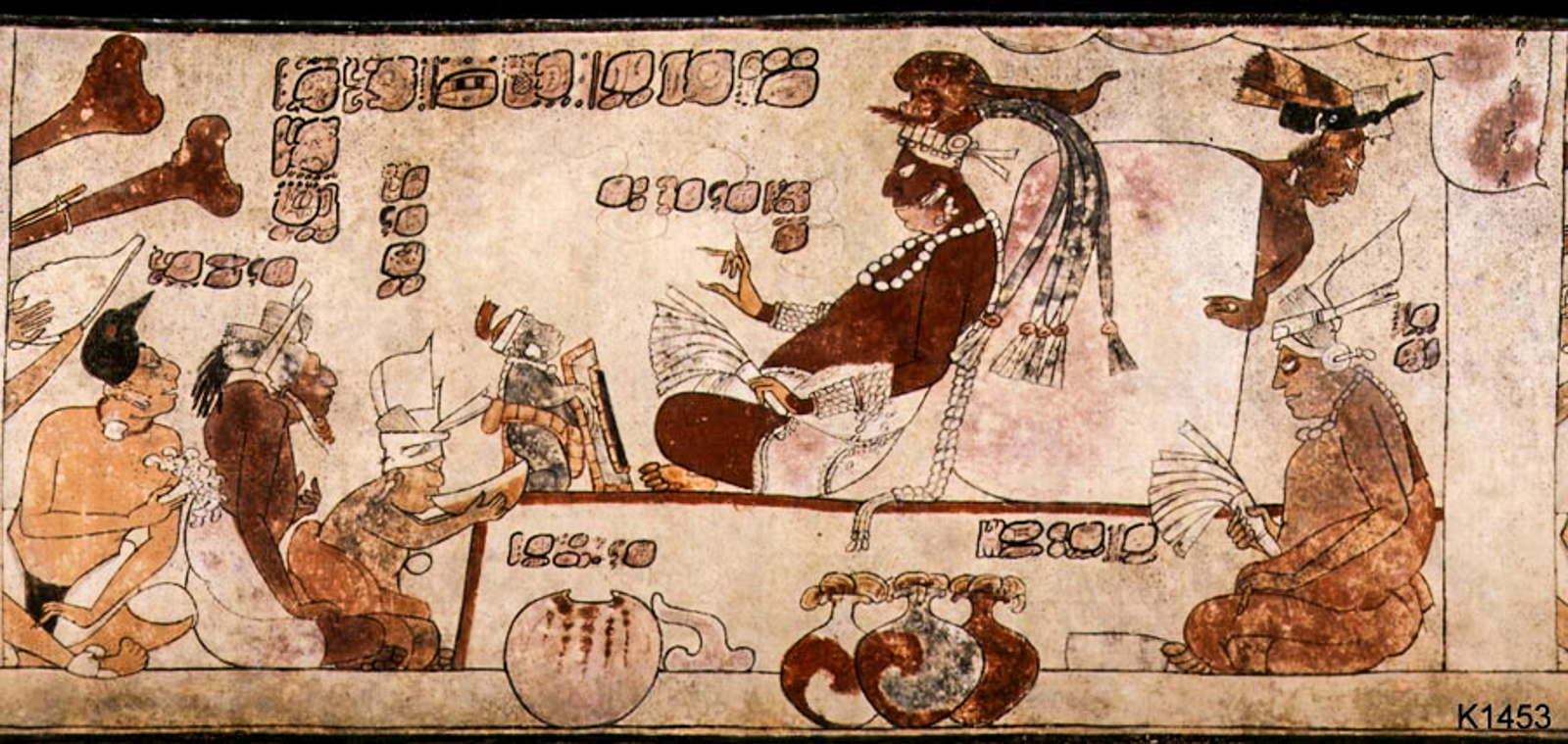

Vase rollouts courtesy of Justin Kerr

Scholars observed that whenever kings are depicted on monuments, they stand higher than those around them. This indicates their elevated status and positions them closer to the sky and the celestial gods. On vases, where palace scenes are depicted, they may sit lower. But the throne signifies their anointed, higher position relative to others. Only the gods had the power, by virtue of divine lineage, to seat a king of the throne.

Maya thrones were first seen in the Guatemalan Highlands in the Late Preclassic period (300 BCE—300 CE). Their presence in the Lowlands shows up in the second half of the Early Classic period, most notably at Uaxactun. In these early periods, thrones were made of chicozapote and logwood. At Tikal, where there was a sizable woodcarving industry, portable and stationary thrones were elaborately carved and had large cushioned backs covered in jaguar pelts—as shown above.

Masonry thrones appear in the Late Classic period. These were usually wide with curling arms on the front and cushioned or painted stone backs. Above, the cushion has the face of a god and hieroglyphs painted on the side—probably both sides. Thrones could be painted in a variety of colors, but red dominated because it symbolized the life force.

The most elaborately carved masonry throne backs with hieroglyphs were discovered at Piedras Negras. Here, Throne 1 is designated a “Reception Throne.”

Feather-bedecked cloth bundles on the thrones, like the one seen here left of the king, are believed to contain sacred objects, the bones of deceased ancestors, heirlooms and other objects of power. Here, the painter shows the king’s body facing us, but in the actual scene it would have faced the visitors—believed here to be presenting him with tribute gifts of cloth. The man kneeling shows the traditional sign of respect by touching both his shoulders. Both visitors wear bulky loincloths and tall paper headdresses with feathers, identifying them as members members of a court—emissaries. Under the throne at right is an often-seen stack of paper, written records that we refer to today as “codices.” The back of the throne is covered in a jaguar pelt.

The white background in this scene indicates that this activity may have taken place outdoors, perhaps along a palace wall. Indoor scenes usually have a yellow-orange background, and overhead there are often drapes that are shown tied up. Many thrones were covered in thick, woven reed-mats. So common was this, the mats came to symbolize kingship. In the inscriptions, the throne was often referred to as “the mat.” For instance, “Lord… rose to the mat,” or “Seated on the mat was Lord…”

Throne rooms were found in multi-roomed and multi-functioned buildings, always on the ground floor. And they usually faced east, north or south. At Aguateca there’s a very wide doorway so those in the courtyard could observe the lord on his throne. Typically, the lord served as a judge in resolving disputes, delegated tasks, proclaimed policies, held audiences with members of his community and received emissaries and lords from other communities.

For a comprehensive read on the subject of court players and functioning, I recommend Royal Courts Of The Ancient Maya: Volume 1: Theory, Comparison, And Synthesis by Takeshi Inomata. It’s expensive. Universities with anthropology departments are likely to have it in their library.

(The vase rollout photographs appear here are through the courtesy of Justin Kerr).

The Jaguar Throne

Excerpt from Jaguar Rising (p. 509—511 )

(In the story, “Bundled Glory” is a personified ancestor bundle).

I PULLED ASIDE THE HEAVY DRAPE AND ENTERED THE TEMPLE. Pine needles crunched under my sandals, their scent faint compared to the odor of burnt coals, incense and ash. I found the brazier I was told would be in front of the throne, and held my torch to it. Gradually, the flames rose and the chamber lit up. “Ayaahh!” I gasped. The throne was huge, well beyond what I expected—a thick stone slab five strides wide, four or five deep and thicker than my head resting on four great boulders. Raising my torch and looking up, I saw the red wrapping of Bundled Glory lying along the front edge of the throne. Four gigantic black beams rose from the corners of the chamber to an incredibly high peak, so high and dark I could barely see the thatching.

Censers shaped like frogs with open mouths stood on large mushroom-shaped stands on both sides of the doorway. To free my hand, I put the torch in a wall holder, took some ocoté sticks from a basket, lit them at the brazier and put them in both censers. A handful of copal nuggets from another basket sent bright puffs of the sweet odor up to the ceiling. Bats fluttered their disapproval then settled. Even though I could only see a bit of the god bundle, I announced my presence out loud. The sound bouncing off the walls reminded me of the great cavern behind the Mouth of Death.

As eager as I was to get a closer look at the throne, the figures painted on the walls captured my attention. “Ballplayers,” I said. A swipe of the wall with my finger removed a thin veil of soot. An eye. Another swipe with the palm of my hand revealed the face of a man wearing a blue macaw helmet with yellow ear ornaments. His eyes were huge—bright and determined. “Ayaahh!” I cried aloud—“Beautiful!”—and my voice bounced off the walls. The blue of the helmet feathers was as deep as the waters beyond Axehandle. The grit came off the wall easily, but my hands were dirty and I was leaving smudges. Not to make things worse, I went to the basin and washed—anointed?—my hands, face and feet with the holy water. I also wet my headband so I could wash off even more soot from the walls. Because of the chill in the air, I pulled the blanket higher on my neck and tied the ends under my chin.

In the mural closest to the door, a lord wearing a winged cape and bird pectoral stood poised as if to open a ball game ritual. The scepter he held up was a huge claw-shaped obsidian hafted with twisted cords that dangled blue feathers. A longer wipe along the wall revealed a cape of lush green feathers that formed the wings of an enormous macaw. Yet another swipe revealed serpent heads painted on the sides of a dark brown hip protector—a ball game player standing as a Macaw ancestor or god. His proud posture and the “smoking-earth” sign he stood on told me he was celebrating a victory.

There were more figures on the wall behind the throne, but they were obscured by its shadow. On the other side, there were lords outfitted with ball regalia displaying the familiar postures of the Hero Twins. Crossing the doorway to where I’d started, I noticed a kneeling figure alongside a standing man wearing the jeweled sak huunal. A swipe of the cloth revealed a jaguar tooth choker. Another showed a knotted waist cord with jaguar teeth dangling over a jaguar kilt identical to one I’d seen my father wearing when I was recuperating. There he was on the wall—My father as a sprout, kneeling before his father’s offering bowl, assisting, perhaps even witnessing the appearance of the founder—Ancient Root—in the smoke that billowed over their heads. I pointed to them. Father. Grandfather. Great Grandfather. Ayaahh! Three generations of ball players. Seeing them in full regalia I realized why my failure at the game had been a deep disappointment for My father.

More swipes over Ancient Root’s shoulder, face and headdress called to mind the murals at Pa’nal where the brother’s lines there were thin and flowing, enclosing open areas of color. The lines on this wall were well made but were thicker with less color, and filled with crosshatching and detailed designs in the fabrics. Lighter, more fluid hands had conjured the maize god at Pa’nal. These hands were stronger, their brushes thicker. And after bearing down on the outlining stokes they went back with a finer brush to put in details, even repeating lines to enhance the effect of texture. I was also seeing different kinds of people playing the game. Many of the decorative scars, body colors and tattoos were not familiar to me. Neither were the signs that decorated their headdresses and clothing. I wished that Charcoal Conjurer could have been there. He would have known what they meant and where the rulers came from.

Aside from the faces on the censers that sat on the four corners of the great slab, the only indication of it being a jaguar throne was a snarling god-face with jaguar ears carved on the front. Atop the steps and in back, I noticed that the throne was covered with layers of tightly woven reed-mat—explaining why rulers spoke of being seated on the “Mat.” On top of the mats was the largest, most plush jaguar pelt I’d ever seen.

Bundled Glory lay in front of it, where it’s head would have been. There were sacred knots tied along the top and on both ends of the long red bundle.

I sat cross-legged in front of it and kept the blanket over my shoulders. If I closed one eye, the knot on top and in the center of the bundle lined up perfectly with the middle of the doorway. Coming in, I’d noticed that the doorway itself lined up with the center of Flower House across the plaza. For some unknown reason, even as a sprout, I was in the habit of lining things up. I sometimes wondered if I’d inherited it from Mother’s father, since he aligned the Great Ball Court that way.

Bundled Glory made me nervous. I think he approved of my looking at the conjurings on the walls, but I didn’t like being watched by a spirit. “With respect Ancient Root,” I said. “Dreams Of Smoke Flint said you know me.” I paused to let him speak but he didn’t. “Lord K’in and Chaak Ek’ determined that I am here as the Succession Lord.” Again I paused. “I am greatly honored to take counsel with you.” Silence. “I am here in preparation for my accession.” Getting no response, I asked about my father, Gourd Scorpion, and Comb Paca, and White Grandfather. All I heard was the occasional rustling of bats high above and the licking of flames in the brazier below. “Did you see the ball game in the Great Court?” I praised the man—or men—who conjured the figures on the walls. “With respect holy lord our founder, I have come to take counsel with you. Do you have anything to say to me?” I waited and waited. My thoughts wandered to Red Paw. How could he talk to me like that? He should be grateful… What do I want? I want him to go on dancing and stop criticizing me! He was right about one thing. The ancestors were not the only ones leading me down this path.

I shook my head to stay awake. “With respect Ancient Root, is it true? Did Chaak Ek’ sacrifice himself so I rather than my brother would sit here?” No response. “You had to have seen how we defeated the Cloud of Death.” How could Thunder Flute lie about my prophecy? Still, like Mother said, it is coming true. He should see me now. Especially tomorrow.

____________________________________________________________________________

For a brief description of The Path Of The Jaguar novels: Go to the Home Page—Novels

Links To Amazon.com for paperback books and Kindle Editions —

Jaguar Rising: A novel of the Preclassic Maya

Ancient Maya Period Ending Rites

Calendar dates that warranted the “planting” of a monument

Lord Smoke Shell, 15th Ruler of Copan. Stela N (Front)

Period endings in the long count were the greatest of ritual occasions for Classic-era Maya kings. Nearly all of the stone stelae at sites such as Copan, Tikal, and Yaxchilan were meant to commemorate these days and, most especially, the ceremonies that the rulers oversaw in their celebration: casting incense, drilling fire, sacrificing war captives, as well as in a rite called ‘the binding of stones.’ One of the principal duties of Maya kings… was to tend to time, ensuring its good health as yet another manifestation of k’ub, the sacred order of things.

David Stuart, author The Order of Days: Unlocking the Secrets of the Ancient Maya.

Like everything else in the Maya world, certain time periods were deified and personalized. Periods of 5, 10, 13, 20 years and more were perceived as gods who carried them—and their characteristics— on their backs with a neck strap or tumpline. At the end of a period, for instance a year, the god set his “burden” down and the next god in line picked it up in an endless repetition of cycles—determined by the movements of planets and stars.

The Maya had two interrelated calendars, one “sacred,” and the other a “Long Count” based on the zero date of the world being created—September 8, 3114 BCE in our calendar. Period Endings were always counted by years from that date, and the ancients referred to the setting up of stelae as “seatings,” similar to the seating of a king on a throne. The Period Ending rites celebrated rebirth and renewal by the erection of monuments, just as the hearthstones were set in the cosmos by the creator gods.

It was not assumed that the world would continue. Any one of the period-carrying gods could decide not to assume the burden set down by the previous god, and that would be the end of the world. To express gratitude to the outgoing deity and encourage the next one to assume his burden, the ceremonies associated with period endings were elaborate, involving bloodletting, ecstatic dancing, shapeshifting and the ritual burning of sacred objects. By providing heat and light, reflections of strength and vitality, the stone monuments were endowed with life. These were huge events for the entire population throughout the Maya area. The Spanish chronicles mention one New Year festival where more than 15,000 people came to one location from as far away as 90 miles.

The likeness of kings, their associations with various deities, ritual performances and other exploits were featured on the stelae because they personified the gods being celebrated. Over time, through ritual, the cycles prompted the repetition of mythological and historical events. And physically, applying an agricultural metaphor in the inscriptions, the Period Ending monuments were “wrapped” in a cloth shroud and “planted” in the ground in the manner of a farmer planting maize seeds. At its dedication, the shroud was removed, and like the shucking of an ear of maize, the “kernel” of the event was revealed. There are also references to stelae being “tied” in bands of cloth in the manner of kings being “tied” in a white headband, the symbol of rulership.

Copan Stela N (East Side)

The inscription above states that Lord K’ahk’ Nik Te’ Wi’ (Lord Smoke Shell) planted his “banner stone” on the period ending that marked 3,930 years since the day the world was created—3114 BCE.

The Inscription

“The Long Count was 9.16.10.0.0. 1 Ajaw, G9 was the lord of the night, 1 day was the age of the moon, it was the first lunar month of the third lunar trimester, Mih K’uh Chapat was the name of the lunar month, of 30 days was the duration of the lunar month, 8 Sip was the position of the solar month; it was planted … the stone … flower of fire … [by] K’ahk’ Yipyaj Chan K´awiil, holy lord of Copan. The count was 0 days, 0 Winal, 10 Tun years, 19 Winikhaab, 17 Pik and 14 Piktun; then came the date 1 Ajaw 8 Ch´en; the god Ajan planted another stone…”

Breakdown of the 9.16.10.0.0 long count

-

- 9 Baktuns 9 periods of 144,000 days [approximately 3,600 years]

- 16 K’atuns 16 periods of 7,200 days [approximately 320 years]

- 10 Tuns 10 periods of 360 days [approximately 10 years]

- 0 Winals No 20-day months

- 0 K’ins No days

Copan Stela N was dedicated by K’ahk’ Yipyaj Chan K’awiil (Lord Smoke Shell) in 761 CE. It celebrated the completion of 3,930 years since the zero creation date. Period Ending rituals were prime examples of two indigenous principles: “As above, so below.” The order in the cosmos must be repeated on Earth. And time is cyclical. “What goes around comes around.”

Completion of a Tun (Year)

Excerpt from the novel, Jaguar Wind and Waves (p. 102)

BECAUSE LORD K’IN MADE HIS DESCENT into the Underworld in the west, considered the place of death, the monuments of deceased rulers were set in a row along the East Platform, in front of the shrines at Precious Forest, their stone faces facing west. To protect them and the alters in front of them from torrential downpours in the rainy season, they were covered over with thatch shelters, some as high as four men standing on shoulders.

I’d heard that my father had dedicated a monument two years earlier to celebrate the completion of the seventeenth k’atun, a twenty-year Period Ending, so I took the children to see if we could find it. Whether because of our plain dress, broad-rimmed rain hats, or so many people milling about in the plaza, we were not recognized. There were lines in front of the monuments, petitioners waiting to present their offerings to the holy men who, along with their prayers, fed them into fires in front of the altars. Thirty paces from the last and tallest monument I recognized Father’s headdress. I covered my mouth and couldn’t hold back the tears. The carver had chosen to show him from the side. Even so, the shape of his nose—longer than I’d remembered—and the slant of the forehead, folded eyelids, full lips, and broad shoulders left no doubt that, although taller and heavier, this was my father.

I pointed out his name to the children—the jaguar paw in his headdress. The little fish nibbling on a lily pad next to it showed him to be the guardian of fertility. Because the sak huunal, the jeweled white headband that marked him as the portal through whom flowed the life of the caah, and because First Crocodile would soon be wearing it, my son was especially interested to see the jade-carved face of Lord Huun on the front of Father’s headband. The last time I saw him wearing it was the day I left for Tollan.

Completion of the 16th Tun

Excerpt from the novel, Jaguar Rising (p. 200)

Eight days later, Lord Yellow Sun Cloud, the Great Tree of Mirador, celebrated the closing of the sixteenth tun at Lamanai. Word came to us that both his underlord sons—Laughing Falcon and Smoking Mirror—witnessed it. White Grandfather conducted the five-day Period Ending ceremonies at Cerros, and the entire caah turned out to witness the year-bearer setting down his burden. Instead of sacrificing the youngest daughter of a minister as they had at Lamanai, he offered sixteen peccary and three turkey hens. After the gods feasted on incense and the ch’ulel in their blood, we feasted on the remains, cooked in an earthen pit.

____________________________________________________________________________

For a brief description of The Path Of The Jaguar novels: Go to the Home Page—Novels

Links To Amazon.com for paperback books and Kindle Editions

Jaguar Rising: A novel of the Preclassic Maya

The Maya Triadic Architectural Complex

Reminiscent of the Three Hearthstone “Thrones” in the Sky

The Maya began erecting enormous pyramid platforms that had three temples on top, two facing each other across a plaza and the third centered behind them. Above, I’m looking down from the central temple atop the platform called “Caana” at Caracol in Belize. In 2000, extensive excavation was underway, and my lens wasn’t wide enough to include the other temples.

This is the central pyramid. The previous photo was taken atop these steps, between the coverings protecting large scucco masks from the rain. Prominent scholars believe the temples were named for the hearthstones in the sky. Having been established there by the creator gods to center the universe, the three stones (prominent stars in Orion) were considered to be “thrones.” Accordingly, they were called “Jaguar Throne Stone,” “Snake Throne Stone.” and “Water Throne Stone.” Why these names is not known. Click here to see what the Caana “Sky Palace” looks like today. The initial construction of Caana was in the 7th century AD 650–696. It had at least 71 rooms.

Researchers refer to this structural pattern as a “Triadic Complex.” The earliest was built at Wakna, a sprawling and largely unexcavated site in Central Guatemala. In the same region and around the same time, more than fifteen triadic structures were erected at El Mirador. “El Tigre,” built around 150 BCE, is as tall as an 18-story building. A mile-and-a-half away and facing it, “Danta” rises fifty feet higher than El Tigre, making it the tallest pyramid the Maya ever built. The second-largest triadic pyramid complex after El Mirador is also nearby at El Tintal. It rises to a height of 150 ft. with a base measuring 344 x 256 ft.

Events recorded at Palenque, Chiapas suggest that later on, the triad complex may have been a standard format for religious and ideological rituals, possibly accession and bloodletting rituals. And there’s evidence that the pattern persisted. Maya researchers Nicholas Hellmuth and Francisco Belli Estrada found an original, handwritten relación of Nicolás de Valenzuela, a Spanish conquistador that includes a comment on a building arrangement and function in the settlement of Sac Balam, “White Jaguar,” a Lacandon Maya city in southern Mexico.

There are one hundred and three houses, including three of community use…In the center of this town of Sac Balam you find three community houses, one from east to west, another from north to south, and the other from east to west, each one looking out on the other, leaving in the center a spacious atrium.

Nicolás de Valenzuela

The researchers concluded, “The layout of Sac Balam fits the triadic pattern, with the buildings ascribed to “community” or public use as opposed to private use or personal residences.” Considering the time depth of the triadic pattern, there had to be a basis in religious myth and beliefs relating to the creation of the world.

Initiation at the Caaha, Caracol

Excerpt from the novel, Jaguar Sun (pp. 390-393 )

(NOTE: In the story, the characters refer to the three temples as “shrines.”)

BEFORE I COULD BE PRESENTED TO LORD RADIANT SUN—who needed to accept me as a “venerable” before I could offer him or any other ruler counsel—I had to undergo a final rite of initiation where I would sacrifice my blood and seek wisdom in three shrines. Also, I would be given a name appropriate to a master of the K’uhuuntak Brotherhood.

Wearing our white robes with our tall headdresses pointing back, Grandfather Sun, Venerable Margay, Venerable Jade, Venerable Storm, Venerable Fire and I were led by a third learner to the tallest pyramid at the heart of Caracol. I’d been instructed not to carry my baton. The masters however, carried wooden plaques that bore the likenesses of former K’uhuuntak masters at Caracol. The painted black lines over a red background on the plaques indicated that they had ascended to the final order in the sky—as a bright light.

The masters formed a circle around me. As each plaque was held to my face and censed, they spoke the master’s name and petitioned him to guide my quest for wisdom and a proper name. When that was done, Grandfather Sun pointed up the steps, beyond a range of rooms that ran from one side of the pyramid the other, to three shrines atop steep pyramids higher up. “Talk to the mountain lords as you talk to us,” he said.

“Out loud?”

“If you like, but that is not necessary. They speak through your ch’ulel.”

With the censing done, the learner went back to the lodge and the six of us climbed the steps. The risers were nearly as high as our knees so we had to go up on all fours, reverently bent low as the builders intended. After resting a while on the seventh terrace, we continued on and entered into a room in the middle of the long range. Through a doorway we faced another broad stairs that led to a spacious courtyard and the three tall pyramids. Despite our slow climb, we had to sit on the top step to catch our breath. Venerable Margay said the shrines atop they pyramids were named for the gods of the three hearthstones in the sky. He said they are called “throne mountains,” because they were used as such by the long line of Radiant Sun lords.

Rising nearly as high as a ceiba to my right, was Water Mountain. Facing it across the courtyard was Serpent Mountain. And straight ahead, in the center, was Jaguar, the tallest of the three stone mountains. Seeing the steep steps, I asked if I would be allowed to rest between visits. Venerable Jade advised me to take the steps slowly and catch my breath at the top. “When you are breathing normally again,” he said, “enter the shrine. Before you speak to the gods, turn away from all distractions.”

Grandfather Sun had advised me to call the gods by their mountain names, and then see myself as them. “Put them on as you would your cloak.” He’d said this several times in my preparation, but he could see in my eyes that I still didn’t understand. Taking my wrists in his hands, he told me to see myself in water to speak with Lord Water, see myself as the Great Serpent Way when I sat with Lord Serpent and see myself a jaguar when I spoke with Lord Jaguar.

Venerable Margay handed me a piece of obsidian. From Venerable Fire I received three strips of white cotton to collect my blood. And Venerable Storm gave me a ceramic bowl to place them in. “Take the blood from your ears,” Grandfather said. “When you come down from each shrine, put the bloodstained strip in the censer and offer your gratitude into the smoke.” The censers were already burning at the bottom of the stairways. “Do not speak to us when you go from shrine to shrine. Water first, then Serpent. Jaguar last. Take as long as you need. If it takes until dark, so be it. We will be here waiting. Remember to ask for your name in each shrine. We need to know what to call you as a venerable.”

GOING UP THE STEPS OF WATER MOUNTAIN, PASSING BEWEEN stuccoed likenesses of Lord Water, made me feel like I was being judged and found guilty of not ever having prayed to him or offered him incense.

At the top, I regained my breath by walking around the terrace. Standing higher than the canopy, the horizon was an unbroken line of trees. I could see the long causeway, the “stems” that led to the district “petals” where smoke rose from the plaza clearings. Close to the western horizon, I guessed the cluster of smoke trails to be those of Ucanal. The Jaguar shrine blocked my view of the east, but looking north and west I could see through the trees, a segment of the white causeway that led to Naranjo.

The sun poked long fingers of light through the clouds, seeming to point to sacred places in the green canopy. In all directions, the giant ceiba’s rose above the other trees, striking poses like naked white dancers with raised arms and red plumage.

Breathing normally, I entered the white-painted shrine, looked at the water band scrolls painted waist high on the walls and then sat on a carved wooden bench with a high back—the throne. After I offered a silent greeting to Lord Water, I drew blood from my ear. The pain was much less than I thought it would be, but it surprised me to see how much blood came from such a little scrape—and how long it took for it to no longer show up on the cotton strip. Because the seat of the throne was high, I kept being distracted by the view of Serpent Mountain through the doorway, so I moved to a plastered bench built into the wall at the end of the long vaulted chamber.

I closed my eyes. With respect, Lord Water, what wisdom do you have for me? Remembering that Grandfather Sun told me to become water in order to talk to Lord Water, I thought of water in several places—the overflowing basin at Itzan, the floodwater rising in my cage at Dos Pilas, the dye colors running to the ditch alongside Lord Cormorant’s workshop and the rain poking holes in the deep pool at Xunantunich. Then I remembered the man at Tikal telling how ash from the mountain of bones blanketed the reservoir.

Clothe yourself in—. The only water I wanted to clothe myself in was that runoff, carrying the ashes of Father, Jade, Flint and Chert across the plaza, down to the reservoir. So not to lose them in the great expanse of ash, I imagined them as red blankets that Father gave us after one of his raids.

Rain poked holes in the blankets. They were breaking up and separating, so I pulled them together, wrapped the great blanket around me and tied it at the neck. As the rain changed from poking to pounding, I went under the water and allowed us to descend—away from the noise and splashing, into the depths where there was calm and quiet.

Suspended, with light above and darkness below, I felt like I didn’t need to ask for anything—not for wisdom or a name, not even for my rightful place in the world. Although I couldn’t see them or their faces, I felt my Father and brothers with me, almost closer than we’d been in life. We are together now, all clothed as water. All the same. The differences between us are gone.

All that you seek is here.

Conversing with my ch’ulel had become so familiar, it took no effort and provided great comfort. Where? Here?

A loud buzzing startled me. I opened my eyes and waved off a wasp. Having been pulled to the “surface” so abruptly, I got up and went swimmingly to the doorway. Far below, scores of people were going their way in the plaza. Workmen carried bamboo poles for scaffolding, and holy men fed offerings into their fire circles while young women carried firewood on their heads. I hadn’t noticed the activity and noise when the venerables and I entered the plaza. Now it was as I’d been warned—a distraction. Waves. Turbulence. The people, the gleaming red temples and other structures enclosing the plaza, even the forest beyond seemed like a thick layer of sorts, like a band of life situated between the ground and the sky.

All this is surface. We are born, we live and die within this band of life. Wars and forced migrations stir it up and leave fear in its wake. Those who survive can barely think of anything else.

Wanting to continue my journey into the depths, I went back to the bench and sat cross-legged with my robe pulled around my knees. I closed my eyes again and descended into the depths with the red blanket wrapped around me. In the deep calm again, I asked, With respect, Lord Water, pardon the interruption. I was told you would speak wisdom to me—through my ch’ulel.

Wisdom is knowing who you are beneath the skin.

All my life, people have asked me who I am. Nothing I said to them feels true—or full enough.

As clear as if Yellow Fire were standing across from me in his cage, I heard him say, I am the substance of clouds, the substance of wind and rain, of forest and trees, the substance of jaguar and macaw, of earth and water…

Of everything. All that is. It is true for you. True for everyone.

The substance of—everything? What does that—?

That wasp—or a different one—buzzed around my head again. I kept my eyes closed and tried to wave him off. He persisted and I was back on the surface again.

Wasp? Is that the name you are giving me? Venerable Wasp?

____________________________________________________________________________

For a brief description of The Path Of The Jaguar novels: Go to the Home Page—Novels

Links To Amazon.com for paperback books and Kindle Editions

Jaguar Rising: A novel of the Preclassic Maya

Jaguar

Lord of the Maya Underworld

The jaguar was the most powerful animal in the ancient Maya world. It’s not surprising that it played a prominent role in mythology and kingship. Piecing together the interpretations of several scholars, mythically, K’inich Ajaw, the Sun god, created the jaguar to represent him in the world. He gave him the color of his power (reddish-orange) and the voice of thunder (the voice of the sun), and entrusted him to watch over his creation.

Each night, when K’inich Ajaw descended into the “West Door” and entered Xibalba he ruled as “Jaguar God of the Underworld,” the name that scholars gave him. In Maya art and inscriptions he represents the night sun and darkness. He’s often shown as paddling other gods through the waterways of Xibalba in a canoe. In these representations, he became known as “Jaguar Paddler.” During the day, he was considered “Lord of the Middleworld.” As a symbol of hunting and war, he was “Waterlily Jaguar,” shown wearing a waterlily on his head and a sacrificial decapitation neck-scarf. All his personifications, including “White Owl Jaguar” and “Baby Jaguar,” were patron gods, different ones for different polities, depending on the preference of the ruler.

As a symbol of the sun’s power, only kings wore jaguar pelts. These could be the complete pelt including the head, the body-skin only, a helmet covered with pelt or tufts of fur adorning wristlets, capes, belts, loincloths and sandals. A clue for scholars, when a bit of jaguar tail was used as a headdress ornament, the wearer’s name included Balam, “Jaguar.” It turned out, many headdresses depicted in Maya art provided the full name of the wearer. When a king sat on a throne adorned with a jaguar pelt it was understood that he represented K’inich Ajaw, the Sun-eyed Lord.

Maya kings went to war with their patron-deities. The kings engaged in battle to demonstrate that their patron was the more powerful. An example is illustrated on Tikal Lintel 3 of Temple 1 (scroll down). In 695 A.D. Tikal defeated Calakmul in a major battle. Calakmul’s enormous palanquin, a wooden platform carried on the shoulders of many men (perhaps slaves), was called “Jaguar Place.” Riding on it, above the seated ruler, was Yajaw Maan, “Five Bloodletter God,” the Calakmul patron deity, an effigy of a huge jaguar with claws outstretched standing high above a throne where the Tikal king, Jasaw Chan K’awiil, sat in regal splendor wearing an enormous headdress. Scholars believe the effigy was taken to Tikal in a triumphal parade where a temple was built for “him.” The king effectively “domesticated” him and acquired his power, thereby winning the respect of his people for the added protection the deity would afford.

For the ancient Maya and most indigenous cultures, the primary concern was with the within of things, their spirit, because that was the source of power. It’s why every element and force in nature from hurricanes to mosquitoes, had a god. And everyday affairs went well or poorly depending on the divinely appointed ruler’s ability to negotiate with them. When a commoner saw his king parading on a palanquin wearing a jaguar pelt, it wasn’t just the skin of an animal being worn as a costume. The pelt itself endowed him with the power of the sun, power over life and death, not just for all who witnessed it, but for the world.

Unlike the panthers in Africa, jaguars have black spots in their rosettes. And some jaguars are completely black. They range from northern Mexico to northern Argentina, living mostly in tropical forest. These lonely hunters are more active at night, prefer places near water with dense forest coverage and unlike other felines are as agile in the water as well as up trees. Their bite is also the most powerful among felines, killing their prey, usually by the neck, in a single bite.

Parade Of The Captured Jaguar Palanquin At Tikal

Excerpt from the novel, Jaguar Sun (pp. 125-126)

Jaguar heads emerged from the smoke of numerous censers, one on each corner of the swaying palanquin. Behind them, red-painted dwarfs stood on the pelts with their backs to us, holding censers. Painted or embroidered on their white capes was the face of Tlaloc, the storm god of Teotihuacan, reminding me that this was a commemoration as well as a victory celebration. The white skulls hanging from the dwarf’s belts sent a chill through me. I wouldn’t allow myself to think that they belonged to my father or brothers, so I looked down at the platform and the men too numerous to count who bore it on their shoulders. In front of the dwarfs there were two more little men, similarly attired and also holding censers, except that they wore wreaths of parrot feathers.

The Divine Lord Jasaw Chan K’awiil himself, sat on a jaguar pelt with its head hanging down the side. He grasped the K’awiil, god of abundance, scepter in his right hand and let the god’s serpent foot rest on his thigh. The other hand grasped a long, red-painted fabric bundle which, because of the stone face sewed on the side, I took to be either his or a captured god-bundle. Rising well above his headdress and the enormous spray of quetzal feathers with the face of the sun god prominent in the middle, the snarling patron of Calakmul, Yajaw Maan, looked like a bigger and more menacing version of Underworld Jaguar. Like him, his orange and black arms were extended, but he grasped a black staff tied with white knots in the manner of Tikal’s sacred headband. The staff, standing at least the height of three men with a snarling jaguar head at the top, told us that he now held the office accorded to a patron of Tikal.

From such a distance, and with ear ornaments and feathers attached to his headdress, I couldn’t see the ruler’s face. Suddenly, I needed to see it—to see his eyes. If I was right about where the palanquin would stop and he would step off, I saw a chance to get closer. Torches had been stacked high on both sides of the palace steps and there were warriors standing ready to light them and hand them out.

I went down the back steps, ran around the backs of the shrines and the ball court and waited in one of the walkways where the torches were stacked. I waited and waited. Then, when the warriors began lighting the torches and passing them along so every warrior on the plaza floor would have one, I approached and asked if they needed help. Clearly they did. They couldn’t light and hand them out fast enough. I gathered up torches, held them one at a time to be lit, and passed them on. With the torches all handed out, and with the plaza looking like a city on fire, I was able to stand with a torch of my own as the palanquin passed about thirty paces in front of me.

The Tikal ruler was younger than I expected, not much older than me. Keeping his gaze forward with a blank expression and relaxed posture, he seemed to say he deserved to be treated like a god.

The bearers stopped and set the platform down gently, being careful to keep it level. The dwarfs, as revered beings sent by the sky gods to honor and assist rulers, approached their master. One of them held out a long red pillow to receive the scepter. Another took his embroidered, pearl-studded tobacco bag, while the two behind them held their torches high to keep the flames well away from the enormous sprays of quetzal feathers that, when he stood, framed his body and towered the height of a man over his head. Considering the weight he carried—in addition to the headdress of stacked sun god masks and heavy jade ear ornaments, a long pectoral of jade stones that rested on a cape of shell-plates, a carved jade head the size of a fist that hung from his belt, two more jade ancestor faces strapped to his legs and ankles and jade tubes in his ears—it was a wonder that he could even stand.

____________________________________________________________________________

For a brief description of The Path Of The Jaguar novels: Go to the Home Page—Novels

Links To Amazon.com for paperback books and Kindle Editions

Jaguar Rising: A novel of the Preclassic Maya

Mangrove Trees

Building material and healing remedy

After touring Cerros, a Preclassic Maya site in Belize, my guide took me a few miles down the New River to a lake covered in lily pads. The ancients cultivated them in great quantities to freshen ponds and encourage the growth of fish. The pads and stalks were dried to fertilize fields. Significantly, the lily pads played a key role in referencing the beginning of time and annual time cycles. Kings wore representations of lily pads in their headdresses, to associate themselves with aquatic deities.

Coming back from the river, the guide slowed the boat and steered it into the tree-line with lianas streaming down without an inch of land. I helped him push the veil of vines aside and we entered a tiny lagoon.

Inside, we were surrounded by thin, tall trees—red mangrove. They converged overhead like the dome of a cathedral, their roots digging into the ground on both sides. The guide informed me that the “ground,” was mangrove wood turned to “peat” that had accumulated over the years and the banks were closing-in on both sides. The long roots support the trees against battering waves, especially on coastlines where there’s also a changing tide. High up, the leaves filter out and excrete salt from the water. I was in awe of the place—so still and quiet with lots of colorful fish swimming among the roots.

In the time of the ancient Maya, both black and red mangrove trees lined the banks of most rivers and saltwater inlets. They used the wood of the red mangrove, in particular, for construction posts in houses and other structures. Besides growing strong, tall and straight the wood is more salt-tolerant than other species, excluding it from being taken up in its roots. The little salt that is taken up, is stored in the leaves. When they’re full, they fall. It’s said that an acre of red mangrove can produce a ton of leaves in about a month. The Maya (and other cultures) used them to make a refreshing tea.

Different mangrove species around the world have been found to have numerous healing abilities because their tannin contains anti-fungal, antibacterial and antiviral properties. Mangrove tree bark, leaves, fruits, roots, seedlings and stems are currently used to heal wounds and treat diarrhea, stomachaches, diabetes, inflammation, skin infections, conjunctivitis (pink eye), and toothaches. It can even be used as mosquito repellent.

One study showed that compounds in red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle) tannin reduced gastric acid and increased mucosal protection to help heal stomach ulcers. Another study revealed that the tannin reduced bacterial strains such as the Staphylococcus aureus, which can cause skin and respiratory infections as well as food poisoning. The ancients also used mangrove roots to make dyes for tanning.

All around us, bobbing on the water like upright string beans, were many dozen of 10-12 inch long seed-pods. Researchers refer to them as “propagules” because they grow high up on the parent tree. My guide pulled one of the pods from the water and explained that they fall and float some distance to disburse, “looking” for water of suitable depth. When they become waterlogged they sink to the bottom and germinate to form the roots of another tree. The experience was so moving, I made it the setting for an important scene in Jaguar Rising: A Novel of the Preclassic Maya.

Maya archaeologist Heather McKillop, believes the abandonment of an Early Classic site, Chan B’i in Belize, and later inundation of the salt works in Paynes Creek, “may be related to mangrove disturbance. The felling of mangroves to establish workshops, alongside the impacts of trampling halted the production of mangrove peat at the workshop locations, with the rising waters subsequently covering the sites.” Mangrove peat was used extensively to enrich soils.

The Mangrove Ecosystem

It’s estimated that two-thirds of the fish we eat spend part of their life in mangroves. This is because the underwater roots provide an ideal protected environment for young fish. Because their roots hold the soil in place, they prevent erosion and degradation of the coastline during hurricanes and storm surges. They store 10 times more carbon in the mud than land-based ecosystems, which is a major defense against rapid climate change. And they reduce ocean acidification, which helps to prevent coral bleaching. A case has been made by some researches that mangroves do more for humanity than any other ecosystem on Earth.

Increasingly, mangroves are being threatened by rising sea-level, water pollution and in some cases being cut down to provide better ocean views. They’re battered by wave-strewn trash, goats eat them and barnacles choke them. Of native mangrove around the world, 35% have been destroyed, mostly due to shrimp farming. Once gone, the land erodes and tides and currents reshape the coastline, making it nearly impossible for them to grow back. After Typhoon Haiyan devastated the Philippines’ coastal communities, the government planted a million mangroves but because the trees were planted without regard to locating the right species in the right places, many of them died.

A palm-frond lies among baby mangrove seed-pods

My guide backing the boat out of the mangrove “temple.”

Mangrove trees symbolize strength and support. The image of their intertwined roots evokes several questions relevant to the human situation. For instance, who and what anchors us in the ebb and flow of everyday living, including the emotional storms that threaten to topple our dreams, desires or decisons? Who comes to mind as the person or persons who provide regular and ongoing acknowledgment, encouragement or inspiration? Who can we count on when the going gets tough? What can I myself do to stay grounded in purpose? And how can I support the people in my circle?

In a world moving at hyper-speed, where so many of us are anxious because of the rate of change, the soulful move is the move toward contemplating the source of things deeply rooted in eternity, the things that always are.

Phil Cousineau, American scholar; screenwriter

Fire Eyes Jaguar Shows Butterfly Moon The Mangrove Temple

Excerpt from Jaguar Rising: A novel of the Preclassic Maya (pp. 216-218)

Approaching my special place, I paddled even harder and she gripped the sides of the canoe. Roots and canopy with thorns in between. Sorcerer’s talk. I turned sharply toward a wall of brush that covered the eastern bank and fronted a forest of tall mangrove trees. “Before I take you home I need to tell you something. Not out here where everyone can see.”

“You should take me home.”

“I know. But jadestone promise, I will not touch you.” I stopped the canoe in front of the wall of vegetation and we changed places so I could stand on the bow to open a passage into the tangle of prickly brush, vine and trees. Butterfly helped me pull us through the vegetation. On the other side, we entered into an open space, a dark grotto, where the water was reddish brown but clear and shallow. “I come here when I want to be alone,” I said. Mangrove trees rising straight and very tall surrounded us. Overhead, they bent together to form an arched canopy with tightly interlaced fingers.

“This must be what a temple is like,” Butterfly whispered.

“It is a temple,” I said. “House of the Mangrove Lord.” Almost within our reach on both sides, mangrove fingers anchored the trees in muddy banks. And tiny fish nibbled at them. Had it not been for the dappled sunlight, we would have thought it was dusk.

Butterfly’s hands covered her chest. She was feeling what I felt the first time I entered the grotto. “How did you find this place?”

“I saw a fisherman come out when I was running a message down river.” I reached over the side and plucked one of the hundreds of long pods that floated upright. “Mangrove seeds—red mangrove,” I said handing it to her. “They fall from the canopy, drift and eventually sink to the bottom. Wherever it sticks, it grows a new tree. When hundreds grow together like this, their fingers get thick and grip into the mud to made new land.”

Butterfly shook her head. “How do you know so much?”

“I have many teachers,” I said. Sitting well back from her, I took a deep breath. “That day at the bench when you brought me tamalies?” She nodded. “Thunder Flute set a burden on my shoulders—something I need to tell you.”

“He was scolding you? Red Paw said the bench is where he—”

“Laughing Falcon ordered him to tell me something he did not want me to know until the Descent of Spirits. You are not going to like this, but it will change my life. It already has. I want you to hear it from me.”

Butterfly gripped her arms, as if from a chill. “You are frightening me.”

I took a breath, but it didn’t calm my pounding heart. “Thunder Flute is not my father. I am not a Rabbit.” Her eyes fixed on mine and a little wrinkle appeared in her brow. “Mother was gifted to him in gratitude for saving the life of a powerful man’s son—when he was on expedition. This man gave her to him, not knowing that I was growing in her belly. No one knew, not even the man who planted his seed in her. She was too afraid to tell him. I touched the earth when the expedition was on the way home. It happened in a cave, while Huracan was throwing a tantrum.”

“Did he tell you who your father is?”

“He is called Jaguar Tooth Macaw.”

“I have heard that name. Your mother might have—”

“He is the Lord of Kaminaljuyu—about forty k’inob south of here.

“Lord? Like Smoking Mirror?”

“Higher. Much higher. More like his father at Mirador.”

Like not feeling a cut until it is seen, it took a moment for Butterfly to understand the implications of what I was saying. When she did, she pulled back. “Then your blood is hot!” The canoe rocked as she went to her knees, steadied herself and bowed with crossed arms.

“Do not do that,” I said. “Get up. We can—”

Butterfly cowered at my feet. “I do not know what is proper,” she said. “Forgive me, I do not know what to say.”

I tried to explain further, but she wouldn’t say anything. I backed the canoe out of the brush. Underway again on open water I realized she might never speak to me again, so I spoke the whole truth about White Grandfather’s dream of me sitting on a rock watching stars that stand still, about finding rather than capturing the doe and fawn, about journeying to the other worlds and the misery of living at the lodge—caused by Thunder Flute. Still, she wouldn’t respond.

At the last bend in the river I paddled hard into the lagoon. In silence, we passed White Flower House, the docking area, the old district and then the long stretch of forest that backed on the Rabbit reservoir.

______________________________________________________

For a brief description of The Path Of The Jaguar series go to the Home Page—Novels

Links To Amazon.com for paperback books and Kindle Editions—

Jaguar Rising: A novel of the Preclassic Maya

Ancient Maya Feasts And Banquets

Insuring the location of power

Vase rollout photo courtesy of Justin Kerr

The above scene could be a “snapshot” of a ruler hosting a feast. Others are likely attending, evidenced by two long wooden trumpets (left top) and a hand beating a drum (below the trumpets). The canopy overhead indicates an interior room, likely a palace. Honey is fermenting in the narrow-necked jars below the ruler, who gestures to a dwarf holding a mirror so he can see himself. (Note the ruler’s long fingernails). Another dwarf, below the dais, drinks from a gourd. Because the Maize God had a dwarf companion, so rulers kept them close.

Along with marriage and warfare, feasting was an important institution for building and maintaining alliances. It provided a context for the presentation of tribute and wealth—at times in a plaza where everyone could see. And it served as a form of “prestation,” a social system where attendees were obligated to the host in some way.

Even feasts where noblemen or lower status individuals served as hosts, those attending were obligated to give another such feast in return. If the guest died in the interim, his heirs inherited the obligation. Competitive or “ritual feasting” was ostensibly for the benefit of the community, but it was equally a way for a potentially powerful person to step up the ladder of importance. Anthropologist Joanne Baron writes about La Corona, a medium-sized site in Guatemala that played a key role in advancing the influence of the Snake Kings. The rulers there “encouraged the active participation of non-elites in public rituals, for example, by encouraging or requiring them to attend feasting events in honor of patron deities.”

Feasts were often held in honor of ancestors, to celebrate calendar events, religious rites, royal accessions and war victories. In wealthy houses, tamales were served in earthenware bowls and platters so each person could have his own. Bernardino de Sahagún, a Franciscan friar, wrote about the preparations for an elite feast. “Ground cacao was prepared, flowers were secured, smoking tubes were purchased, tubes of tobacco were prepared, sauce bowls and pottery cups and baskets were purchased. The maize was ground and leavening was set out in basins. Then tamales were prepared. All night they were occupied; perhaps three days or two days the women made tamales… That which transpired in their presence let them sleep very little.”

Diego de Landa, another Spanish priest, reported that “sumptuous feasts were attended by many and lasted a long time. They spend on one banquet what they earned by trading and bargaining many days. To each guest, they give a roasted fowl, bread and drink of cacao in abundance, and at the end, they gave a manta to wear and a little stand and vessel, as beautiful as possible.” It was also noted that others were fed from the kitchen of the ruler, starting with the visiting nobility, the guards, priests, singers and pages, down to the feather-workers and cutters of precious stones, mosaic workers and barbers.

Art historian, Dori Reents-Budet, an expert on Maya vases and their imagery, found that dignitaries from aligned polities and even people from adversarial polities were invited. Gifts were usually exchanged before the feast, including polychrome vases and drinking cups, cotton mantles, crafted adornments, cacao beans, bundles of feathers and foods. And chocolate, a highly valued beverage, was served. The vases depict banquets in plazas and dancing with musical accompaniment in long buildings, some with curtains and long benches for seating.

Feast to Celebrate the Protagonist’s 12th Birth Anniversary

Excerpt from the novel, Jaguar Rising (p. 16 )

To prepare for the feast, married women cleaned pots, shook out the long reed-mats and tended the cookhouse fires while the younger ones made trips to the reservoir. Butterfly Moon Owl, my friend’s sister and daughter of Mother’s feather-worker, carried two of my cousins astride her hips while balancing a water jar on her head. Neighbors came with knives and digging tools to help my uncles slaughter the peccary and prepare the cook-pit while their wives helped with the flowers and other foods.

After the chores were done, families would bring even more food and flowers, and they would stay until the sun set over the western forest. On some occasions, as a favor to Father, purple-robed ministers wearing blue-green quetzal feathers and jade adornments would come to celebrate with us. If they came at all, they would come toward the end of the day, compliment the women on the food and amuse us with flowery words and puns to make us laugh. Before taking their leave they would offer a little gift, usually a shell or polished stone. Father, always the spokesman for the Rabbits when he was home, would express his gratitude for their coming but we all knew that they came because our ruler, Lord Laughing Falcon Cloud, had ordered it.

More to my liking were the tradesmen who always came. These were canoe carvers, stone workers, cord-winders, bead-makers, fabric dyers and tanners, the people Father relied upon for his expeditions. They didn’t just sit and talk. They played games and demonstrated their skills with axes, spears, and blowguns, heaving hand-sized stones into water buckets and building human pyramids. When they finally tired and went to the brazier to tell stories and drink, we sprouts would run to the forest and play hunting and warrior games. The older flowers tended the younger ones in a clearing there, so one of our games was to see how close we could get before surprising them with war cries and chases with our imaginary axes and spears. The Mothers wouldn’t let us use sticks but sometimes we did—and denied it when the flowers told on us.

Lady Jaguar Prepares a Feast For Her Husband’s Guests

Excerpt from the novel, Jaguar Wind & Waves (p. 99)