Ancient Maya Ancestor Veneration

The old men used to say that when men died, they didn’t perish, they once again began to live. . . They turned into spirits or gods. — Alfred Tozzer, American anthropologist

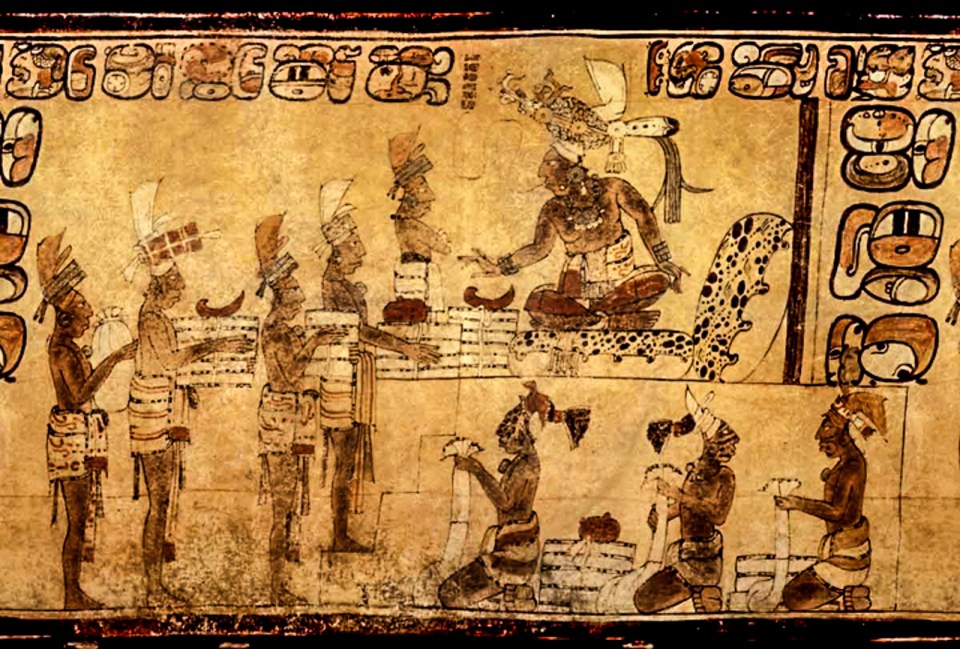

This is likely a noble ancestor depicted on the frieze of a council house at Copan, Honduras.

Among the ancient Maya, evidence of ancestor veneration shows up around the first century B.C. At that time, decisions were being made about the inheritance of land use. Land was not owned, but the right to use it was handed down. The principle of first occupancy gave preferential access to a man’s descendants because his house was built over his deceased ancestors who came to be regarded as guardians of the house and proximate fields and forests. When the ancestor was the founder of a lineage and a pyramid-temple was of raised on the site, it would be called his nah “house.” And the entire site would be considered “the home of…”

Ancestor veneration ultimately is not about the dead, but about how the living make use of the dead; it’s a type of active discourse with the past and future, embodying the centrality of Maya understanding of death and rebirth.

Mark Wright, Anthropologist

While ancestor veneration provided the rules of inheritance, it often created conflict between household heads and their heirs. Maya anthropologists observe that ancestor veneration promotes and perpetuates inequality and alienation from resources within the household as well as the polity. In times of hostility, the tombs of royal ancestors were plundered. Naranjo Stela 23 (Guatemala) records the desecration of the tomb of a Yaxha Lord.

Kings often venerated their ancestors by having their heads float above them on monuments, facing down at the top of the composition. Piedras Negras Stela 5 shows the king’s ancestor beneath the Principal Bird Deity at the top. The Maya regarded the human head as the place from which breath, the vital force, emanates. A Maya text confirms this —

Each ancestor guards the boundaries of his land. When the spirit leaves (the body), the head goes with the spirit, just down to his shoulders. His strength and his head and his heart go wherever they want to. The head and face confer honor as well as being honored.

In the Classic Period, ancestor veneration was politicized, used to sanction elite power and authority. Kings would enter their ancestor’s burial vault and perform ceremonies involving fire and the sprinkling of blood and incense. This is depicted on Piedras Negras Stela 40 and Tikal Alter 5.

In some places the kings deified their ancestors. This, of course, meant they inherited divine blood. And it put them on a trajectory toward becoming deified after death. Further, a king could make the case to his royal household that his ancestors—and later themselves—would protect them and guard them against usurpers when “they took the dark road.” Died. When several generations of ancestors were buried in the same location, a pyramid-shrine could be built over it, and continuously expanded. This made the place sacred, in some cases a pilgrimage destination.

Idols of the apotheosized ancestors were often the recipients of sacrificial offerings. Made of wood and painted blue, these figures were heirlooms that were passed down through the generations. Spanish chronicles indicate that these idols were carved during the Maya month of Mol’ and the preferred wood was cedar.

They made wooden statues and left the back of the head hollow, then burned part of the ancestor’s body and placed the ashes in it and plugged it up… kept in their houses… great veneration… made offerings to them so they’d have food in the other life.

Frey Diego de Landa, Spanish priest

Not all dead relatives were venerated, only lineage heads and people of position. Their remains were treated preferentially. Both men and women were candidates for ancestor status. Because the bones of deified ancestors were sacred, they were kept in bundles with other sacred objects. Considered relics that contained power, these objects frequently appear beside kings seated on thrones depicted on painted vases.

Vase rollout photo courtesy of Justin Kerr

Here, the bundle containing ancestor relics sits on the throne behind the king, under the feathers being presented to him. Below the throne is a vase containing tamales dripping with sauce, perhaps chocolate.

Maya iconographer Carl Taube observed that “Only kings or other high nobles could look forward to resurrection and a return to this diurnal paradise and dwelling place of the gods and euhemerized ancestors, called Flower World or Flower Mountain. Flower Mountain is depicted in Maya art not only as the desired destination after a ruler‘s death, where he would be deified as the Sun God, but also as the paradisiacal place of creation and origin. Evidence for the belief in Flower Mountain dates to the Middle Formative Olmec (900-400 B.C.) and is also attested to among the Late Preclassic and Classic Maya as well, from about 300 B.C. – A.D. 900.”

Maya communities today maintain lineage shrines that go back many generations.

The source for much of this information is A Study of Classic Maya Rulership by anthropologist Mark Wright’s 2011 Dissertation.

A Healer’s Advice: Gather Your Ancestors Around You

Excerpt From Jaguar Wind and Waves (p. 141-142)

Whenever your husband—or anyone else—says or does something that ruffles your leaves, stand tall and watch. Let it blow past you. The amaté neither blames nor scolds the wind. It thinks not of lashing back. It knows it has deep roots. It trust that it will hold.”

“By roots you mean my ancestors?”

She nodded. “Call out to them by name. Ask them for strength when the winds blow strong, when the waves threated to drown the real you. You were brought up trusting and revering your ancestors, were you not?”

“I was. But I was also taught to speak up, not let a man treat me like a dog.”

“The greater part of standing and watching is knowing who you are and what you stand for. The warrior has his shield, the turtle has its shell, the house has its roof. Human beings hold to the truth of who they are in order not to be crushed.”

“I have become so busy with the household, my children, and my husband’s torments, I have lost the truth of who I am. That is what I want back. So whatever he says or does, you want me to just stand and watch? Say nothing? Do nothing?”

Lady White Gourd nodded. “For now, until your flower is whole again. When he sings a song or dances a dance that offends you, stay steady inside yourself. Allow it and listen. You do not have to be offended or hurt by anyone. Choose not to be hurt. Let the winds blow past. Offer no resistance. Just stand firm. Remember your roots and say to yourself: ‘stop, drop and endure.’ No resistance, not even in thought. Put away the part of you that wants to resist. And let the wind and wave pass. Then, as quickly as possible, remove yourself to a quiet place where you can be alone. Gather your ancestors around you like a blanket, and offer words of gratitude for what they have given you. Name it—what you received from them. And ask them to calm the storm.”

____________________________________________________________________________

For a brief description of The Path Of The Jaguar novels: Go to the Home Page—Novels

Links To Amazon.com for paperback novels and Kindle Editions

Jaguar Rising: A novel of the Preclassic Maya

Jaguar Wind And Waves: A novel of the Early Classic Maya

Jaguar Sun: The Journey of an Ancient Maya Storyteller

___________________________________________________________________________

My other sites—

Love And Light greetings.com: A twice-weekly blog featuring wisdom quotes and perspectives in science and spirituality intended to inspire and empower

David L. Smith Photography Portfolio.com: Black and white and color photography

Contemplative Photography: A weekly blog where a fine-art photograph evokes a contemplation

Ancient Maya Water Management

The rise and fall of intensive agriculture in the Maya area

In this model of central Tikal, Guatemala the dark-colored basins indicate the location of large, very deep reservoirs. The entire city was built with slopes so the runoff would fill them during the rainy season, and these sustained the city all year long.

Around 2000 BCE, much of the Central Lowlands of the Yucatan peninsula consisted of year-round wetlands (bajos or swamps). The rainy season usually insured the swamps would be inundated, but during the dry season they dried up and solidified like concrete. Agriculture was only possible January through February and again May through June when enough rain fell to soften the clays without completely flooding them. Year after year, a major challenge for the kings and calendar priests was to manage the alternating lack of water and its abundance within the same area by appealing to chaak, the god rain and thunder.

To the north there were cenotés, large collapsed limestone depressions or sinkholes that contained ground water. There were no rivers or lakes in the central lowlands because the limestone bedrock completely absorbed the rainfall. East to Belize and to the south, there were some rivers and shallow lakes fringed with waterlilies, cattails and grasslands.

In the lowland heartland, the Maya planted two crops during the rainy season on elevated ridges. In the dry season they cut canals through them to speed the drainage of the rainy season’s floods, allowing for earlier planting at the beginning of the dry season and extending it long enough to harvest two dry season crops.

Beginning around 100 CE, most of the surface water in the swamps disappeared. Several feet below them is a layer of what was once moist wetland peat, rich with pollen from trees, aquatic plants and maize. At the end of the Preclassic (around 300 CE) and for the next 500 years, the soil was buried in successive layers of waterborne limestone clay. As the population grew, slash & burn farming—burning trees to make fields for crops—decimated the forest. With the trees gone, the rain washed away the soil, and the limestone beneath it eroded to powder which ran downhill filling the swamps with fine-grained clay.

By 250 CE (Late Preclassic), the bajos silted up and the surrounding wetlands were gone. For five months of the year, water was scarce. Nakbe and El Mirador, two of the earliest and largest cities the Maya ever built were abandoned. Water collection became paramount. Pyramid temples, shrines, palaces, platforms, plazas, stairways and roads were constructed so runoff from the rains would empty into to reservoirs. At Tikal they dug 10 reservoirs with a 40-million-gallon capacity and sealed them with black clays from a swamp east of the site.

The making of plaster, mortar and stucco to pave plazas and coat buildings—to make them smooth and gleaming white in the sunlight—required the felling of trees to burn limestone. To create a lime kiln, they stacked logs about 5 ft. high in a circle, leaving a 1 ft. wide hole in the center. On top, they heaped a layer of crushed limestone about 30 inches high. Then they dropped leaves and rotten wood into the center hole and set it on fire. The kilms burned for about 36 hours, from the bottom up and inside out. What remained was a pile of powdered quicklime.

When the builders were ready to plaster, the powder was mixed with water and thickened. As it dried on a surface, it became calcium carbonate, which made a hard, smooth, bright white and long-lasting plaster. In places, paved steps, courtyards and plazas were 3 1/2 ft. thick. Esteemed Maya scholar, Michael Coe, cites the production of plaster as a primary reason why the lowland forests were depleted by Late Classic times.

The Maya farmed the remaining shallow swamps by cutting irrigation ditches into the limestone clay and building up mounds beside them for planting. Many of the lowland cities were built on islands in these swamps. A variety of hydraulic systems were employed, different at different places and times. These included—

- Mucking. Nutrient rich muck from the swamps was hauled out in back-baskets and dumped on fields to create topsoil.

- Agua Culture. Ponds in Belize and shallow reservoirs in other places were dug to cultivate lily pads. These provided an ideal habitat for fish, and the pads were used for mulch.

- Hillslope Terracing. Rock walls were built horizontally and stacked vertically to contain crops and take advantage of natural watering. In the highlands entire hills and mountains were terraced.

- Canals. These were cut to create irrigation features and raised fields that could be farmed seasonally or year-round. Evidence of the earliest canal (between 200 BCE and 50 CE) encircles Cerros in Belize like a necklace. It was 20 ft. wide and more than 7 ft. deep, ideal for canoe traffic. At Edzna, on the coastal plain of Campeche, Mexico, among her 21 canals, one of them is 10 miles long, with a moat 300 ft. across. The soil and limestone taken from the moat were used to build the ceremonial complex. It’s estimated that the canal and moat took 1.7 million worker days.

- Chultuns. In outlying communities, caverns were dug into the limestone and lined with clay to hold large amounts of water. They served as wells during the dry season. In the large cities, chultuns were also used for dry storage.

- Springs, Wells and Waterholes. These occurred in the Guatemalan highlands. They were considered sacred, so ceremonies and rituals were held there, and ancestral gods held council at them—to review their descendant’s affairs. At Dzibilchaltun in Northern Yucatan, there were over 100 small wells.

- Raised Fields. These were created by digging a wide path through a swamp and depositing the muck on both sides to create long strips of dry land that were cultivated. Hundreds of people worked the raised fields year-round. These are seen today at Xochimilco not far from Mexico City.

Researchers claim that intensive agriculture resulted in three times the harvest of maize fields, allowing the population to double. Then it doubled again. Water management systems were very successful—for a while. But by the Late Classic (750 CE), the Central Lowland ecosystem’s carrying capacity had been reached. Malnutrition set in—indicated by a sharp decline in the stature of elites. Warfare increased, polities became fractured and there were severe, long-lasting droughts.

By 800 CE, people were losing faith in their ruler’s ability to garner favors from the gods—especially to produce the right amount of rain at the right time. As conditions worsened, people moved away. The reason for the “collapse” of Maya Civilization is still debated/ Certainly, there were many factors. And it was a gradual, century-long process. The timing and management of rain was certainly a prime contributor.

My sources:

Much of the information on ancient Maya water management systems came from publications by Nicholas Dunning and Vernon Scarborough, particularly the latter’s book The Flow of Power: Ancient Water Systems and Landscapes, and his Water Management in the Southern Maya Lowlands: An accretive model for the engineered landscape, an article published in Research in Economic Anthropology. More on the ideological side, I recommend Precolumbian Water Management: Ideology, Ritual and Power by Lisa Lucero and Barbara Fash.

Making Plaster from Burnt Lime Powder

Excerpt from Jaguar Rising (p. 132-135)

WHILE WE WERE TALKING, BARE-BREASTED AND BAREFOOT female slaves started coming onto the platform. Stone Face went to show them where he wanted their water jugs, and I followed. Behind them, male slaves carrying lime powder were coming up, some of them bent so low they had to lift their chins to avoid bumping into the step above them. Walks relieved the first man of his jar and poured a ring of powder five strides across between the edge of the platform and the line that marked the eastern wall. His apprentices, wearing damp cloths over their noses, emptied the other jars around the circle and continued to build it until the wall of powder came up to their knees.

True to his name, Walks In Stonewater stepped into the center of the ring and, as Stone Face poured in water, he began his “paddle dance.” At first, the powder just clumped like dough balls. More water made the clumps melt and even more brought bubbles and heat. The spreading, clumping and mixing continued until the mixture became so hot Walks had to jump out and stick his feet in a water bucket. Meanwhile, Stone Face had taken over the stirring with a canoe paddle, pushing dry powder to the wet center and vigorously twisting, pushing and pulling the clumps until they formed a smooth slurry.

Walks took another paddle and they worked the mortar until he tired and handed off his paddle to an apprentice. Three of them eventually formed a thick mound of slurry with a flat top. As the mixture approached the consistency that Walks wanted, he went around scooping it up with his paddle, lifting it and dumping it over and telling the apprentices how much more water and powder to add.

A burst of applause and yelps coming from behind the platform drew White Cord and me to go and look. Six white-robed bearers were carrying a mahogany platform into the plaza. On it was a tall red plaster model of the new temple. When it reached the center, Laughing Falcon raised his arms to quiet the crowd. Unfortunately, he was too far away to hear what he was saying.

White Cord speculated. “He is probably telling them how necessary the temple will be to the prosperity of the caah.”

Stone Face came to take a quick look, holding his paddle aside. “It is necessary—how else could he convince his father to come here?” I was tempted to repeat what Thunder Flute had told me about Laughing Falcon wanting to best his brother so he could inherit the throne at Mirador, but decided against it.

With the underlord’s speech ended, the drummers started again and Walks called to me. “Seven Maize! Do you want to see this or not?” I ran over and sat cross-legged beside the apprentices as their master took a fistful of the white slurry and opened his hand in front of us. “See how it does not run between my fingers?” He turned his hand over and it didn’t fall. “If it falls, it is too wet. If you wipe it off your hand and it leaves powder it is too dry. Mortar takes less water and three times more clay than plaster or stucco.” Beside him were two wide mouth ceramic jars. He dipped into the brown one with a small calabash and passed it around so we could dip a finger into the thick yellow ooze. “Smell it,” he said.

“Tree sap,” an apprentice said.

“Holol,” Walks specified. “It slows the hardening. You shred holol bark and pack it tight in a jar. Pour in limewater and let it sit overnight. The next morning you dig it out with a stick and press it through a fine weave basket.”

Stone Face took his paddle and made swirls along the outer rim of the slurry. Walks held the jar over the paddle and slowly began pouring the sticky substance onto it. “Never pour the holol onto standing slurry. It clumps and you get bubbles. And only use one jar for every two jars of powder. No more, no less. This is why we use the same containers and count the jars.”

The younger of the three apprentices asked the reason for slowing the hardening. “Obviously, so we can work it longer,” Walks said impatiently. “If it hardens before we take it to the blocks or while they are being set, it will not hold up. Slow drying mortar lets a block find its proper seating. When it takes comfort in the mortar, it makes a strong and lasting bond.”

Stone Face stopped his stirring and his brother took a handful of fine gray ash from the black jar. Bending down he went around the ring scattering the ash, keeping his hand close to the surface so the wind wouldn’t blow it away. Just watching him made me want to dig my hands into the jar. It seemed so soft. “It may not look like it, but ash is a thickener,” Walks said. “If we were making plaster, we would use less. Stucco, none at all. Since this is going to be mortar and needs to support weight, I will use all of it.”

“With respect,” another apprentice asked, “where do we get the ash?”

“Now that is a worthy question. Always and only from a lime kiln—”

“From the burnt wood, not the limestone,” Stone Face interjected.

“Never from a hearth or brazier. Holy men sometimes want us to use the ash from their censers. Some builders will do it. They say it makes no difference. Maybe not to them, but it does to me. I want my ash to come from the hottest fire possible—so it is clean and fine as dust. Look here—.” Walks held out his hand to show us the fineness of the ash. And when he blew it away there was not even a speck left on his hand. As he scattered the ash and Stone Face folded it in, the mound of white slurry began to turn gray.

Lord K’in was nearing his descent over the western trees and the plaza was emptying out. Laughing Falcon had gone, but there were still men waiting to receive their obligation. Determined to set the first course of blocks before it got dark, White Cord and Walks had the apprentices and me carrying jars of mortar and cloths in buckets of water as needed. Teasing me as he often did, Stone Face said I was too clean compared to the apprentices, so he chased me around the platform, pulled me down and wrestled with me until I was thoroughly coated with powder and plaster dust. As this was going on a lime bearer had come up and told White Cord that White Grandfather was asking for me. Stone Face and I were out of breath, panting when he told us. I was disappointed to leave because Walks said he would let me try my hand at laying some mortar.

____________________________________________________________________________

For a brief description of The Path Of The Jaguar novels: Go to the Home Page—Novels

Links To Amazon.com for paperback books and Kindle Editions

Jaguar Rising: A novel of the Preclassic Maya

Maya Thrones

The seat of divine power and influence

Vase rollouts courtesy of Justin Kerr

Scholars observed that whenever kings are depicted on monuments, they stand higher than those around them. This indicates their elevated status and positions them closer to the sky and the celestial gods. On vases, where palace scenes are depicted, they may sit lower. But the throne signifies their anointed, higher position relative to others. Only the gods had the power, by virtue of divine lineage, to seat a king of the throne.

Maya thrones were first seen in the Guatemalan Highlands in the Late Preclassic period (300 BCE—300 CE). Their presence in the Lowlands shows up in the second half of the Early Classic period, most notably at Uaxactun. In these early periods, thrones were made of chicozapote and logwood. At Tikal, where there was a sizable woodcarving industry, portable and stationary thrones were elaborately carved and had large cushioned backs covered in jaguar pelts—as shown above.

Masonry thrones appear in the Late Classic period. These were usually wide with curling arms on the front and cushioned or painted stone backs. Above, the cushion has the face of a god and hieroglyphs painted on the side—probably both sides. Thrones could be painted in a variety of colors, but red dominated because it symbolized the life force.

The most elaborately carved masonry throne backs with hieroglyphs were discovered at Piedras Negras. Here, Throne 1 is designated a “Reception Throne.”

Feather-bedecked cloth bundles on the thrones, like the one seen here left of the king, are believed to contain sacred objects, the bones of deceased ancestors, heirlooms and other objects of power. Here, the painter shows the king’s body facing us, but in the actual scene it would have faced the visitors—believed here to be presenting him with tribute gifts of cloth. The man kneeling shows the traditional sign of respect by touching both his shoulders. Both visitors wear bulky loincloths and tall paper headdresses with feathers, identifying them as members members of a court—emissaries. Under the throne at right is an often-seen stack of paper, written records that we refer to today as “codices.” The back of the throne is covered in a jaguar pelt.

The white background in this scene indicates that this activity may have taken place outdoors, perhaps along a palace wall. Indoor scenes usually have a yellow-orange background, and overhead there are often drapes that are shown tied up. Many thrones were covered in thick, woven reed-mats. So common was this, the mats came to symbolize kingship. In the inscriptions, the throne was often referred to as “the mat.” For instance, “Lord… rose to the mat,” or “Seated on the mat was Lord…”

Throne rooms were found in multi-roomed and multi-functioned buildings, always on the ground floor. And they usually faced east, north or south. At Aguateca there’s a very wide doorway so those in the courtyard could observe the lord on his throne. Typically, the lord served as a judge in resolving disputes, delegated tasks, proclaimed policies, held audiences with members of his community and received emissaries and lords from other communities.

For a comprehensive read on the subject of court players and functioning, I recommend Royal Courts Of The Ancient Maya: Volume 1: Theory, Comparison, And Synthesis by Takeshi Inomata. It’s expensive. Universities with anthropology departments are likely to have it in their library.

(The vase rollout photographs appear here are through the courtesy of Justin Kerr).

The Jaguar Throne

Excerpt from Jaguar Rising (p. 509—511 )

(In the story, “Bundled Glory” is a personified ancestor bundle).

I PULLED ASIDE THE HEAVY DRAPE AND ENTERED THE TEMPLE. Pine needles crunched under my sandals, their scent faint compared to the odor of burnt coals, incense and ash. I found the brazier I was told would be in front of the throne, and held my torch to it. Gradually, the flames rose and the chamber lit up. “Ayaahh!” I gasped. The throne was huge, well beyond what I expected—a thick stone slab five strides wide, four or five deep and thicker than my head resting on four great boulders. Raising my torch and looking up, I saw the red wrapping of Bundled Glory lying along the front edge of the throne. Four gigantic black beams rose from the corners of the chamber to an incredibly high peak, so high and dark I could barely see the thatching.

Censers shaped like frogs with open mouths stood on large mushroom-shaped stands on both sides of the doorway. To free my hand, I put the torch in a wall holder, took some ocoté sticks from a basket, lit them at the brazier and put them in both censers. A handful of copal nuggets from another basket sent bright puffs of the sweet odor up to the ceiling. Bats fluttered their disapproval then settled. Even though I could only see a bit of the god bundle, I announced my presence out loud. The sound bouncing off the walls reminded me of the great cavern behind the Mouth of Death.

As eager as I was to get a closer look at the throne, the figures painted on the walls captured my attention. “Ballplayers,” I said. A swipe of the wall with my finger removed a thin veil of soot. An eye. Another swipe with the palm of my hand revealed the face of a man wearing a blue macaw helmet with yellow ear ornaments. His eyes were huge—bright and determined. “Ayaahh!” I cried aloud—“Beautiful!”—and my voice bounced off the walls. The blue of the helmet feathers was as deep as the waters beyond Axehandle. The grit came off the wall easily, but my hands were dirty and I was leaving smudges. Not to make things worse, I went to the basin and washed—anointed?—my hands, face and feet with the holy water. I also wet my headband so I could wash off even more soot from the walls. Because of the chill in the air, I pulled the blanket higher on my neck and tied the ends under my chin.

In the mural closest to the door, a lord wearing a winged cape and bird pectoral stood poised as if to open a ball game ritual. The scepter he held up was a huge claw-shaped obsidian hafted with twisted cords that dangled blue feathers. A longer wipe along the wall revealed a cape of lush green feathers that formed the wings of an enormous macaw. Yet another swipe revealed serpent heads painted on the sides of a dark brown hip protector—a ball game player standing as a Macaw ancestor or god. His proud posture and the “smoking-earth” sign he stood on told me he was celebrating a victory.

There were more figures on the wall behind the throne, but they were obscured by its shadow. On the other side, there were lords outfitted with ball regalia displaying the familiar postures of the Hero Twins. Crossing the doorway to where I’d started, I noticed a kneeling figure alongside a standing man wearing the jeweled sak huunal. A swipe of the cloth revealed a jaguar tooth choker. Another showed a knotted waist cord with jaguar teeth dangling over a jaguar kilt identical to one I’d seen my father wearing when I was recuperating. There he was on the wall—My father as a sprout, kneeling before his father’s offering bowl, assisting, perhaps even witnessing the appearance of the founder—Ancient Root—in the smoke that billowed over their heads. I pointed to them. Father. Grandfather. Great Grandfather. Ayaahh! Three generations of ball players. Seeing them in full regalia I realized why my failure at the game had been a deep disappointment for My father.

More swipes over Ancient Root’s shoulder, face and headdress called to mind the murals at Pa’nal where the brother’s lines there were thin and flowing, enclosing open areas of color. The lines on this wall were well made but were thicker with less color, and filled with crosshatching and detailed designs in the fabrics. Lighter, more fluid hands had conjured the maize god at Pa’nal. These hands were stronger, their brushes thicker. And after bearing down on the outlining stokes they went back with a finer brush to put in details, even repeating lines to enhance the effect of texture. I was also seeing different kinds of people playing the game. Many of the decorative scars, body colors and tattoos were not familiar to me. Neither were the signs that decorated their headdresses and clothing. I wished that Charcoal Conjurer could have been there. He would have known what they meant and where the rulers came from.

Aside from the faces on the censers that sat on the four corners of the great slab, the only indication of it being a jaguar throne was a snarling god-face with jaguar ears carved on the front. Atop the steps and in back, I noticed that the throne was covered with layers of tightly woven reed-mat—explaining why rulers spoke of being seated on the “Mat.” On top of the mats was the largest, most plush jaguar pelt I’d ever seen.

Bundled Glory lay in front of it, where it’s head would have been. There were sacred knots tied along the top and on both ends of the long red bundle.

I sat cross-legged in front of it and kept the blanket over my shoulders. If I closed one eye, the knot on top and in the center of the bundle lined up perfectly with the middle of the doorway. Coming in, I’d noticed that the doorway itself lined up with the center of Flower House across the plaza. For some unknown reason, even as a sprout, I was in the habit of lining things up. I sometimes wondered if I’d inherited it from Mother’s father, since he aligned the Great Ball Court that way.

Bundled Glory made me nervous. I think he approved of my looking at the conjurings on the walls, but I didn’t like being watched by a spirit. “With respect Ancient Root,” I said. “Dreams Of Smoke Flint said you know me.” I paused to let him speak but he didn’t. “Lord K’in and Chaak Ek’ determined that I am here as the Succession Lord.” Again I paused. “I am greatly honored to take counsel with you.” Silence. “I am here in preparation for my accession.” Getting no response, I asked about my father, Gourd Scorpion, and Comb Paca, and White Grandfather. All I heard was the occasional rustling of bats high above and the licking of flames in the brazier below. “Did you see the ball game in the Great Court?” I praised the man—or men—who conjured the figures on the walls. “With respect holy lord our founder, I have come to take counsel with you. Do you have anything to say to me?” I waited and waited. My thoughts wandered to Red Paw. How could he talk to me like that? He should be grateful… What do I want? I want him to go on dancing and stop criticizing me! He was right about one thing. The ancestors were not the only ones leading me down this path.

I shook my head to stay awake. “With respect Ancient Root, is it true? Did Chaak Ek’ sacrifice himself so I rather than my brother would sit here?” No response. “You had to have seen how we defeated the Cloud of Death.” How could Thunder Flute lie about my prophecy? Still, like Mother said, it is coming true. He should see me now. Especially tomorrow.

____________________________________________________________________________

For a brief description of The Path Of The Jaguar novels: Go to the Home Page—Novels

Links To Amazon.com for paperback books and Kindle Editions —

Jaguar Rising: A novel of the Preclassic Maya

May the Holidays and the New Year Bring You Peace and Joy

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.

My little horse must think it queer

To stop without a farmhouse near

Between the woods and frozen lake

The darkest evening of the year.

He gives his harness bells a shake

To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound’s the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.

The woods are lovely, dark and deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

Robert Frost, Woods on a Snowy Evening

Thank you for subscribing to Ancient Maya Cultural Traits

David L. Smith

Ancient Maya Prophecy And Belief

Reading the future; healing body, mind and spirit

A prophecy is a message that comes from a deity, delivered to a person attuned to receive it. Typically, the message expresses the divine will regarding the future. Ancient cultures all had prophets who delivered prophecies. And people believed what they heard, were willing to kill and die to be true to it. Gods, after all, were to be trusted.

Anthropologist Mircea Eliade noted that tribal societies believed that their stories, about the gods and sacred ancestors overcoming the forces of chaos, created a sacred cosmic and social order in which humans could safely dwell. He said their myths and rituals divided the world into two realms, the sacred and the profane. Those who live the sacred order are human beings; all others are strangers who come from the realm of chaos and are different and those differences threaten the life-sustaining stability of their sacred order. Around the world, he showed that ancient tribal societies saw themselves as living at the center of the cosmos, the place where the gods and ancestors brought things into being. In such a physical and mental space, trusting the will of the gods and sacred ancestors was inborn, automatic, a matter of life, destiny and death.

As part of the divinely created order of the cosmos, to maintain personal safety and stability in a tribal society, human beings needed to model the cosmic order—maintain the center. There were many threats—rivalry, disease, beasts and demons that roamed the wilds, malevolent deities, climate fluctuations and outsiders. So it was necessary to understand the will of the benevolent gods and appeal to ancestors who in death became guardians of the sacred order.

It is not surprising that, according to archaeologist David Freidel, the Maya institution of “divine” kingship derived from the much earlier Olmec culture in southern Mexico. Maya kings were more than elites who ruled. Their power, at least until the Late Classic period, derived mainly from their ability, along with their priest-daykeepers, to discern the will of the gods and divine the future.

Privileged to meet and photograph a Maya shaman in his Santa Catarina, Guatemala healing center, I took the above picture of the sacred items he used to do a “layout” that would inform him about a client’s health and prognosis. Using two types of beans and crystals, his procedure was to arrange them in rows using sacred numbers. On a trip to Belize, I met a shaman who used beans and crystals in the same way, but an important part of his discernment had to do with the feelings he got in different parts of his body.

Maya kings used psychoactive drugs, auto-sacrifice and ecstatic dancing to commune with the gods and deified ancestors. In the modern era, prophets emerged and we built religions around them. And today there are individuals who claim to be gifted with precognition, the ability to foretell the future. Whatever the underlying reality, then and now, there is no question that belief is one of our most powerful capacities. It’s the rudder that steers the canoe and the ocean liner.

This is a make-believe world. We make it according to our belief.

Jerome Perlinski

Your beliefs become your thoughts.

Your thoughts become your words.

Your words become your actions.

Your actions become your habits.

Your habits become your values.

Your values become your destiny.

Mahama Gandhi

Prophecy Of The Cloud Kings At El Mirador

Excerpt From Jaguar Rising (p. 57-59 )

“According to the prophecy there were to be two trials,” White Grandfather said. “Our grandfathers survived the first. Now it comes to us. And it will not pass when the k’in bearer sets his burden down. It will only pass when the gods see how we are shouldering this, their final trial.”

The same man spoke again. “Respect, Grandfather, people are saying that Laughing Falcon has not bargained well with the gods, they are not honoring his requests.” When others in the crowd agreed, White Grandfather shook his head and looked side to side. Someone called out. “Enough talk! Release the food! Give us the food!” The people shouted, stomped the ground, and clapped their hands. “Food! Food! Food…”

White Grandfather took a step forward and pointed to the crates and baskets beyond the guards. “Do you know where this comes from?” he shouted.

“From us!” someone yelled. Another called out, “Tribute!” Someone else complained that it was his family’s sweat that filled the storehouse.”

“All that we have, all that we receive is a gift from the gods,” White Grandfather said. “Lord K’in provides the heat and light for your crops. The Chaakob water them with rain. One Maize gives us the maize to eat and the seeds to plant. All this and more is given through the appeals, the blood sacrifices, petitions and offerings of Our Bounty. Turn away from what you lack. Instead, fix your gaze on the bounty that is coming, that has been foretold…”

A calmer voice interrupted, “With respect, Grandfather, how can I, when my family is starving? My eyes are fixed on their misery.” The man turned and pointed beyond the guards. “We cannot eat the words of a prophecy.”

White Grandfather bent down. “We understand. We know it is difficult—” A noblewoman next to the man got his attention and spoke. All I could see was nodding behind a deer headdress with a spray of macaw feathers. White Grandfather stood straight again. “The lady asks why the trial has been so long and severe. Those who gave the prophecy did not say. But they understand—when sustenance is withheld, trust, belief, and hope are all challenged. By standing firm against the drought, against the fields of rotting maize, the pain of hunger and the loss of our elders, we show ourselves to be worthy of the abundance they promised.”

“What prophecy do you speak of?” the lady asked. “When and where was it given?”

“The Cloud prophecy, given nine k’atunob past, at Mirador.” In a voice only those around us could hear, a round-faced guard said a one-hundred-eighty-year-old prophecy could not be trusted. He said it was no longer valid.

“I have not heard of it,” someone called out. “What did it say?”

White Grandfather opened his arms and waited for the crowd to quiet. “The prophecy said the destiny of the House of Cloud—and the challenge to its rulers—was to raise temples to Lord K’in and One Maize that reach to the clouds. It said that when this is fulfilled there will be many seasons of abundance, but first, there would be trials—to determine if the people living in the Cloud territories are deserving of such abundance. Further, he said there would be two long seasons when the skin of the earth and skins of the people dry up. There will be too much water and then not enough. A mingling of strong winds from the east and west will bring black smoke, a blanket of death. It advised that we, along with the rulers, make offerings of blood and incense—and stand tall through the trials.” White Grandfather walked closer to the shelter’s roof. “Already, we have raised temples that reach the clouds. Now, if we stand tall—like a forest around our Great Tree—offering our sweat and patience to the gods, the abundance will come.”

A young warrior raised his feathered spear and called from the middle of the crowd. “With respect, did the prophecy come from the Cloud ancestors—or from the gods?”

“Our ancestors gave the prophecy that we might understand what the gods want,” the old man said.

“What do they want?” An older warrior standing beside him asked.

Rather than answer, White Grandfather removed his three-leaf headdress and held it out. Mother whispered in my ear. “Remember what tell—about Those Born First?”

“How they wore three maize leaves in their headdresses?” I answered.

She nodded. “Tipped with jade beads.

“I forget what they were for.”

“Listen,” she said, pointing to White Grandfather.

“This is what they want,” he said. He pointed to the leaves and named them in turn: “Beauty—Respect—Gratitude. To your eyes, they look like maize leaves painted white. To our eyes, they are the seeds that, when sown in the hearts of men, flower into the coming abundance. When we make beauty in our houses and fields, when we show respect for the gods, ancestors, Our Bounty, our brothers and sisters of the caah—all that lives, when we have gratitude in our hearts for what we have been given, the gods will be satisfied. When they see the seeds of beauty, respect and gratitude growing in each of us and in the caah, they will be eager to sustain us, continue the world for another round and bring the promised abundance.”

____________________________________________________________________________

For a brief description of The Path Of The Jaguar novels: Go to the Home Page—Novels

Links To Amazon.com for paperback books and Kindle Editions

Jaguar Rising: A novel of the Preclassic Maya

Sacred Spaces

For the ancients, there was no separation between the secular and the sacred. Everything of the Earth was sacred, ensouled with a vital source that comes from the sun. Outside it was chaotic space, peopled by ghosts, demons, spirits and “foreigners” who were considered demons. Because human beings couldn’t live in chaos, life and living was all about maintaining order. And the model for it was (and remains) nature and the cosmos. In both, they and we observe constancy, beauty, pattern and cyclical motion, apparent features of absolute reality. Modeling these in architectural forms, they created sacred spaces, distinct from the “wilds” of chaotic fields and forests. In a way, using dimensions and forms found in nature, they consecrated a space by making is a universe.

For the ancient Maya, the parts of a house were correlated with parts of the human body and the cosmos. The floor was “feet,” the door a “mouth,” the thatched roof a “head of hair,” the walls the “bones,” and the four corners a replica of the cosmos. Houses were mostly for sleeping; the activities of daily life took place outside. Functional structures, such as kitchens, storehouses and workshops were generally separate from the house because it was not only sacred, it was a living entity. Doorways were open, without doors, to show hospitality. And for privacy, a fabric was pulled across the opening and tied to wooden pegs inserted into the walls.

Making a new structure a “home” a living entity required an Och K’ahk’ “Enters the Fire” ceremony where fire was drilled between three large hearthstones. (On a clear night a “cloud” in the center of three bright stars in Orion is visible—Alnitak, Saiph, Rigel. We know that cloud of gas, dust and stars as nebula M42). By investing the space with life—heat and light—the home reflected health and vitality. At the same ceremony, the shaman offered a blood sacrifice, usually a bird, to entice a spirit—often a deceased ancestor—to take up residence in the house as a protector.

Tikal Temple II

Temples, which were an extension of the Maya home, were considered the dwelling places of the gods. They also replicated caves, places where underworld supernaturals resided. When the temple curtain covered the doorway, the god was asleep in his resting place. At many sites, the inscriptions speak of three hearthstones being places in the sky as one of the founding acts of creation. The hearth in the temple was an essential conduit between it and the cosmic hearth planted by the Maize God. Ceibal, a medium-sized city in northern Peten, Guatemala may have been called “Three-Stone Place” anciently because there was a cache of three jade boulders under a stela in the center of a temple.

In his study of architectural dimensions, archaeologist Christopher Powell found that “the width of most Maya houses in Yucatan consisted of units called uinics ‘humans,’ which are measured by stretching a cord from fingertip to fingertip, with arms outstretched and perpendicular to the body. One uinic was virtually equal to the height of the person who was doing the measuring. Thus, a human being with arms outstretched and perpendicular to the body may be inscribed by a square.” This is seen in many temple doorways that are square. It calls to mind the drawing of the Vitrucian Man by Leonardo da Vinci.

Besides the human form, Dr. Powell also found that the ancients incorporated the shapes of flowers and shells which display Phi, nature’s most common proportion. Flowers have five petals or multiples of five petals. Projected onto the Maya world, there were four directions and a center. “The shapes of houses, milpas, and temples and their works of art all share the proportions inherent in three simple geometric forms: the equilateral triangle, square and pentagon. These three regular polygons, with their square root of two, square root of three, and phi rectangular expressions, provide an underlying structure that unites the Maya cosmos… Pentagonal arrangements of seeds in the cross-sections of fruit are common. The phi equiangular spiral is observed in seashells and snail shells and in the growth spirals of various plants. The Yucatec Maya word for belly button, “tzuk,” or division place, divides the human form by the phi proportion.

In the Popol Vuh, the sacred book of the Quiché Maya, there’s a passage that, according to Dr. Powell, may be viewed as a concise formula for measuring a phi rectangle with a cord.

It took a long performance and account to complete the emergence of all the sky-earth: the fourfold siding, the fourfold cornering, measuring, fourfold staking, halving the cord, stretching the cord, in the sky, on the earth, the four sides, the four corners, as is said, by the Maker, Modeler, Mother-Father of life, of human kind…

Christopher Powell

The ancients used cords (intertwined vines) of different lengths with knots along them to lay out the location and length of walls. To lay out a floor, for instance, a cord was dowsed with white lime powder (pulverized limestone), stretched taught at the specified location and then snapped to leave a white impression, along which the builders would lay their stones to build a wall. The cords were equivalent to today’s measuring tapes, providing a means to create and reproduce lines with consistency over time and place. In this way, they replicated the proportions found in nature and the cosmos.

Geometry and numbers are sacred because they codify the hidden order behind creation.

Stephen Skinner

Ensouling A House

Excerpt From Jaguar Rising (p. 74 )

When Grandfather Rabbit died, Thunder Flute decided that, rather than repair our house, which was next to his and badly in need of fixing, he would follow the common practice by terminating both houses and build a larger one over his father’s bones. Grandmother would move in with us.

Once the masonry platform was built, the house went up quickly. But before we could move in, its skin and bones had to be ensouled with a guardian spirit. Otherwise terrible things could happen. Somehow, within the seven days of the Fire Entering rites that invited a spirit to take up residence in the house, I needed to find a way to be alone with White Grandfather. I didn’t know what I was going to say, but with Thunder Flute being more willing to answer my questions now, I hoped I might learn something before then that would help.

I got my chance when he took me to an old quarry down by the New River. With the ensouling rites just two days away, he needed hearthstones to establish the heart of the house, the place where a spirit would enter. The three stones had to be a certain size and shape for cooking, so we used long-handled axes with wide flats to pull back the weeds, dig out the soil and expose a long section of white stone. The day was hot. Before we began to chop the stone itself, we sat on a ledge, wiped the sweat off our faces and took our keyem—a gruel made by stirring balls of maize dough in water. Mother spiced the dough with honey and chili powder, so I was eager for it.

“You can say your gratitude if you like,” Father said. He knew that Mother had gotten my sister, brother and me into the habit of offering a gratitude for everything we took from the earth, field, forest or water. I was embarrassed to say it in front of him, but he was allowing it. I took off my hat, put my hands flat on the stone and bowed my head.

With respect Earth Lord,

I stand before you—Seven Maize Rabbit.

I speak for myself and for Thunder Flute Rabbit.

In this place of beauty, we offer you our gratitude.

Forgive us for uncovering your face here,

For chopping your white beauty.

We need three of your little ones for our hearth.

We will honor them at the Fire Entering rites.

We will honor them as the heart of our house.

With respect Earth Lord, receive our praise and gratitude.

Thunder Flute scratched some lines in the exposed stone. Following them, he cut grooves with his chisel and hammerstone while I cut into the stone from below. It took all morning, aching muscles and buckets of sweat, but finally, we had a ledge. By stomping on it we broke off three large blocks and rolled them to a pool of water where we could sit in the shade and wash them off as we shaped them.

Using Measuring Cords (At Xunantunich, Belize)

Excerpt from Jaguar Sun (p. 246)

Approaching the broad steps of the temple, I saw again, high up, the beautifully stuccoed figures of men and gods that I’d seen from a distance. The deeply sculpted, brilliant red frieze wrapped around the temple like a headband. At the foot of the steps, Obsidian explained that he and the other workers were the only ones permitted to be up there, so I waited and watched while he and his brother-in-law took the cords to several men who were pacing on the floor above the sculpted band.

It was fascinating to watch my brother moving the measuring cords back and forth and dusting them with lime powder. I couldn’t see when they stooped down, but I knew a firm snap of the cord would leave a white line to show the placement of the walls and doorways so another worker could chisel small holes to mark them permanently for the stone setters.

____________________________________________________________________________

For a brief description of The Path Of The Jaguar novels: Go to the Home Page—Novels

Links To Amazon.com for paperback books and Kindle Editions

Jaguar Rising: A novel of the Preclassic Maya