Ancient Maya War And Warriors

Ritualized skirmishes evolved into large scale warfare

Rollout vase photos courtesy of Justin Kerr

Rollout vase photos courtesy of Justin Kerr

It was the custom among them to pledge what they possessed to each other; upon collection and payment they began to quarrel and attack each other.

Frey Diego de Landa

They never had peace, especially when the cultivation (of milpas) was over, and their greatest desire was to seize important men to sacrifice, because the greater the quality of the victim, the more acceptable their service to the gods.

Alfred Tozzer, Anthropologist

War was the way you got gifts for the gods and kept the universe running.

Linda Schele, Anthropologist

Purpose and Objectives

In the Early period, warfare was practiced as a confrontation between spiritual forces, primarily involving the capture and sacrifice of royal captives. Most valued were captives of high rank. The sacrifice of royal blood was the ultimate gift to the gods. Rather than “battles” between large forces, warfare initially amounted to raids and attacks to take captives. In the inscriptions, what was important was the captive’s name, title and who captured him. A large part of ceremonial warfare amounted to capturing not only a worthy sacrificial victim but also the patron banner of the polity, the ruler’s god-bundle which containing the relics of his deified ancestors, his palanquin and war paraphernalia. All of these sacred items increased the power and prestige of the victor and his lineage. It also brought economic benefits to the community that fueled the emerging elite and contributed to the massing of both commoner and slave labor for construction projects.

According to archaeologist Dr. Arthur Demarest, warfare in the Middle-to-Late Classic was about status and charisma. It helped to define who the royals and elite were and how much power they had with the gods. This was important because knowing who the gods favored provided a means for resolving dynastic succession, it opened trade routes, reinforced the status of elites by providing them with prized possessions such as quetzal, obsidian and jade and it bolstered the victor’s access to tribute labor. Dr. Demerest says, “In this period they did not ruin the enemy’s fields, or take a chance on harming its population because this brought no prestige. The necessary pact between humans and gods was sealed by the bloodletting of rulers.”

Other possible benefits included the acquisition of tribute from subject polities, boundary maintenance, the establishment of warlords which fostered elites and ranking, opportunities for public rituals and spectacles. It legitimized the ruler’s power in dealing with the gods.

Method

Early Maya warfare (Preclassic and first centuries of the Early Classic), pitted the leaders of communities, their noble followers and a reasonable complement of commoner militia against one another on well-known battlefields and on known and planned occasions. I think that Maya warfare had some clear-cut rules of conduct during this early phase of the civilization… The primary tactic was the raid or brief battle aimed at surprise attack and quick defeat rather than total conquest or subjugation.

David Freidel, Archaeologist

Maya artworks show warriors marching behind battle standards—tall poles with large shields attached to the tops, decorated and edged with bright featherwork. (Much larger than those shown here and above). The fighting itself amounted to free-for-alls where the principal lords and warriors, decked out to represent supernatural forces, engaged each other in close-order combat. The sounds of the battlefield came from conchs, rattles, wooden trumpets, wood and turtle carapace drums, whistles and frantic shouting.

Weapons

In the Preclassic period, most polities weren’t large enough to maintain standing armies, so the rulers assembled able-bodied men and boys and armed them with brine-hardened cotton armor, wooden helmets, short stabbing darts, wooden axes with obsidian blades anchored along the sides, spears, axes and slings. It wasn’t until the Postclassic that the Maya used bows and arrows.

Timing

Generally, wars were fought during the dry season, mostly because men would be available after the harvest and before the planting. Aside from agricultural needs, the rainy season with extensive flooding and muddy paths would have made it difficult, at times impossible. The Nacom (chief warlord) presided over an annual festival in the month of Pax (Mid-May). Rites were performed and he was treated as a god and he discussed military matters with the ruler and other members of the court.

A Significant Shift Occurred

According to inscriptions at a variety of sites, on January 31, 378 an emissary from Teotihuacan in Central Mexico called Siyaj K’ahk’ (Born Of Fire) arrived at El Peru/Waka’. On the same day, Tikal’s ruler, Chak Tok Ich’aak (Great Jaguar Claw) “entered the water.” He and his entire lineage were killed and replaced by a new male line drawn from the ruling house at Teotihuacan. Foremost among them was a high nobleman from Teotihuacan named Spearthrower Owl. This event marks the beginning of major changes in Maya society, among them the purpose, strategy and scale of warfare.

The shift was from the modest scale taking of royal captives for sacrifice to the creation and maintenance of city-states through the acquisition of tribute (bounty and labor) from subject polities, the expansion of trade routes, and in the case of the Snake Kings of Calakmul, the establishment of allies to encircle Tikal, their bitter enemy, through marriage alliances. From then on, the “Peten Wars” ratcheted up involving many thousands of warriors in a single battle.

After decades of the Calakmul kings building alliances, on August 3, 695 the current ruler, Yuknoom Yich’aak K’ahk’ (Fiery Claw) led his allies into an enormous battle against the Tikal king, Jasaw Chan K’awiil. In a major twist, Yich’aak K’ahk’ was defeated.

(My novel, Jaguar Wind And Waves, depicts this momentous event).

Postclassic Period (950-1539 AD)

There is evidence of constant warfare in Northern Yucatan among competing city-states throughout these years. The Spaniards reported that Maya armies were large during important campaigns, numbering in the thousands, but they were not maintained very long because they were logistically sustained through temporary appropriations of food and materials from unhappy peasant villagers. And those city-states were then governed by royal families, likely including other elites, rather than individual rulers.

The information provided here derives largely from a collection of scholarly opinions and interpretations. Warfare among the ancient Maya is one of the many cultural practices that changed over time and from place to place. The benefit of collected research and discussion is that it gives us a “taste” of what it was like. In that, we can consider the past as we shape the future.Green-band Raid on Ahktuunal, Guatemala

Excerpt from the novel, Jaguar Rising (p. 35-36 )

Across the plaza at the base of the Great Turtle temple, a similar fate had befallen the Mother of the underlord, members of his council and court including their wives, even his steward. They and the most holy jaguar prophet who speaks to the people on behalf of the ruler and prognosticates for him were also being stripped, bound and tied together. Wherever the green band raiders were from, they apparently needed slaves—probably for construction projects—and a hot-blood for their master’s altar.

Above the chain of captives, the zapote beams of the Holy House of Lord Turtle were engulfed in roaring flames. Tall, red-and-green feather standards on both sides of the doorway burst into flames sending an explosion of sparks into the smoke and fog. With the exception of the residence and the lineage house behind it—where Thunder Flute and Pech were taking cover—all the structures of the central district, the shrines, temples and other structures made of perishable materials, were going up in flames.

The Green Bands brought their looted items to the center of the plaza and dumped them into baskets and onto nets, mats, and blankets, ripping open the tied bundles and spilling out their contents for their leader to inspect. Thunder Flute signed to Pech that he wanted a count of the raiders, including those not in the plaza. In turn, Pech signed an order to an assistant at the back of the Flower House and the message was passed on. Thunder Flute signed again, saying that if the raiders all come together in the plaza, we will attack. If not, they would “target and track” them when they leave. Again, the message was passed. Thunder Flute watched a while longer, then signed again to Pech. Why are they not talking? Pech shook his head and signed back. No one was talking, not a word passed between them.

After parading his prize in front of the warriors, the Owl leader tied the underlord’s neck-cord to the great stone turtle at the base of the temple. The goods being brought into the plaza were more bountiful and precious than Thunder Flute would have thought possible. They overturned a crate filled with ceramic and carved stone turtles packed in dried pine needles. Another contained the hides of deer, peccary, and ocelot. Two of the raiders labored over a large wooden crocodile. With his foot on the back of his neck, he pried out the obsidian eyes with his knife and broke off two rows of shell that served as its teeth. The rest he left, turning his attention to a prickly armadillo goblet offered by a young warrior. When another held out a ceramic censer in the shape of a turtle, he swatted it down and it smashed against the pavement. Thunder Flute noticed that any object carrying the likeness of a turtle—painted, molded, or incised—was either rejected or destroyed.

From a heavy basket, one of the raiders dumped a number of green stones onto a blanket. Thunder Flute wanted to get a closer look so he motioned for Pech to stay where he was while he went around to the back of the residence. Crossing to the council house under the cover of streaming black smoke, he crouched behind a stairway and watched as three of the raiders examined the green stones with their leader. Thunder Flute counted six hand-sized ceremonial celts, at least ten equally long belt danglers, two jade tubes as long as a finger, four jade earflares shaped like flowers, a dark greenstone the size of a fist and scores of jade bead necklaces. When an assistant held one up with the bulbous head of the sun god at the bottom, the leader snatched it out of his hand and stuffed it into his already bulging pouch. From another warrior, he snatched a jade turtle shell the size of a fist, a magnificent piece with three red spots painted on the carapace. With great force, he hurled it down the plaza. Thunder Flute gasped as it hit the pavement and rolled into the smoke.

After dumping some thorny oyster shells, red shell beads, and shell perforators onto a blanket, a warrior with a jagged scar down one arm gathered the ends and slung it onto his back. His brother warriors gathered up the other goods and the leader followed, all the while looking to see if there would be any resistance. There was none. Along the way, he stepped onto the back of a fallen Ahktuunal guard and struck a victory pose with his axe held high. Several of his men imitated the gesture, and together they howled like coyotes.

Thunder Flute took advantage of the distraction. He ran behind the retaining wall to where Pech was watching. Beside him, an assistant pointed to the temple of the Great Turtle. Through the smoke, high on the third terrace and hiding behind a fallen censer stand, a scout was signing: god bundle burned—six guards down. Warriors gone.

Gather their weapons, Thunder Flute signed. Return to the canoes. He whispered in Pech’s ear, “I want a man on the far side of the council house—to see where they will go. The leader threw a jade turtle down the plaza, a big one. I want it.”

____________________________________________________________________________

For a brief description of The Path Of The Jaguar novels: Go to the Home Page—Novels

Links To Amazon.com for paperback books and Kindle Editions

Jaguar Rising: A novel of the Preclassic Maya

Jaguar Wind And Waves: A novel of the Early Classic Maya

Jaguar Sun: The Journey of an Ancient Maya Storyteller

The Ancient Maya Ball Game

Where the story of creation was repeated and celebrated

Ball Court: Copan, Honduras

Scholars believe that in earlier Maya times, the contest was a ritual that represented the fight of the opposing and forces of the universe—life-death, Sun-Moon, day-night, light-darkness—in order to insure balance, continuity and fertility. Some say it was a metaphor for the movements of heavenly bodies, the ball representing the journey of the Sun god passing in and out of the underworld. Because some courts have stone rings on the walls for the ball to pass through, other say it was about the Earth swallowing the sun where the losers would be sacrificed as an offering to the Sun god to insure his rebirth the next day.

In 2008 my guide on the right told how the ball game bore a strong relation to the Popol Vuh account of creation. I had my audio recorder going. The following is an abbreviated version of his account.

The ball game was a ceremony of creation. The Hero Twins, Hun Hunahpu and Xbalanque, danced here and woke up the Lords of the Underworld. The owls came and invited them to go to the Underworld. There, they defeated the bad forces and saved their father who was reborn, apotheosized as Orion in the sky. Hunahpu, Hun Hunapu’s son, was reborn and became the Sun. Xbalanque became Venus. And Xmucane, their grandmother, became the Moon. This is how the Maya universe was created.

The shaman, or specialized dancers of the ball game, were men who prepared their whole lives to fight against the bad forces—storms, earthquakes, epidemics, drought—all of which came from the Underworld. The ball represented the movement of the creators. Everything was alive. The ball bouncing up and down represented sunrise and sunset. And when it hit one of the macaw heads placed in the center and the ends of the risers, it signaled the defeat of the bad forces.

Vucub Kakich, the Principle Bird Deity, oversees the ball court from the riser. The central macaw head is below, a front view beneath a corbled vaulted hallway.

Continuing the story, Hunahpu tried to defeat Vucub Kakich—the vein god who fancied himself more powerful than the Sun—using a blowgun. Repeating that event here in the ball court, the players tried to hit a macaw head with the ball to defeat this great bird. He’s shown in the celestial realm, on the highest level of the court. When the ball hit the floor in the alleyway, it amounted to the Hero Twins knocking on the door of the underworld, a demonstration that they had the courage and power to wake the forces of evil to fight against them. When a king engaged in this enactment of good versus evil it was an opportunity for him to assume the persona of a Hero Twin and defeat death. The ancients didn’t look for winners or losers. They wanted a hero, somebody who had the courage to fight against the forces of evil.

Sacrificial Rituals

According to the inscriptions, losers were decapitated, their heads symbolic of the “sacred sun” ball. At Yaxchilan and possibly other places, the heads of war captives were thrown from the top of a long stairway, emulating the rolling of the ball. This was briefly depicted in Mel Gibson’s 2010 movie, Apocalypto.

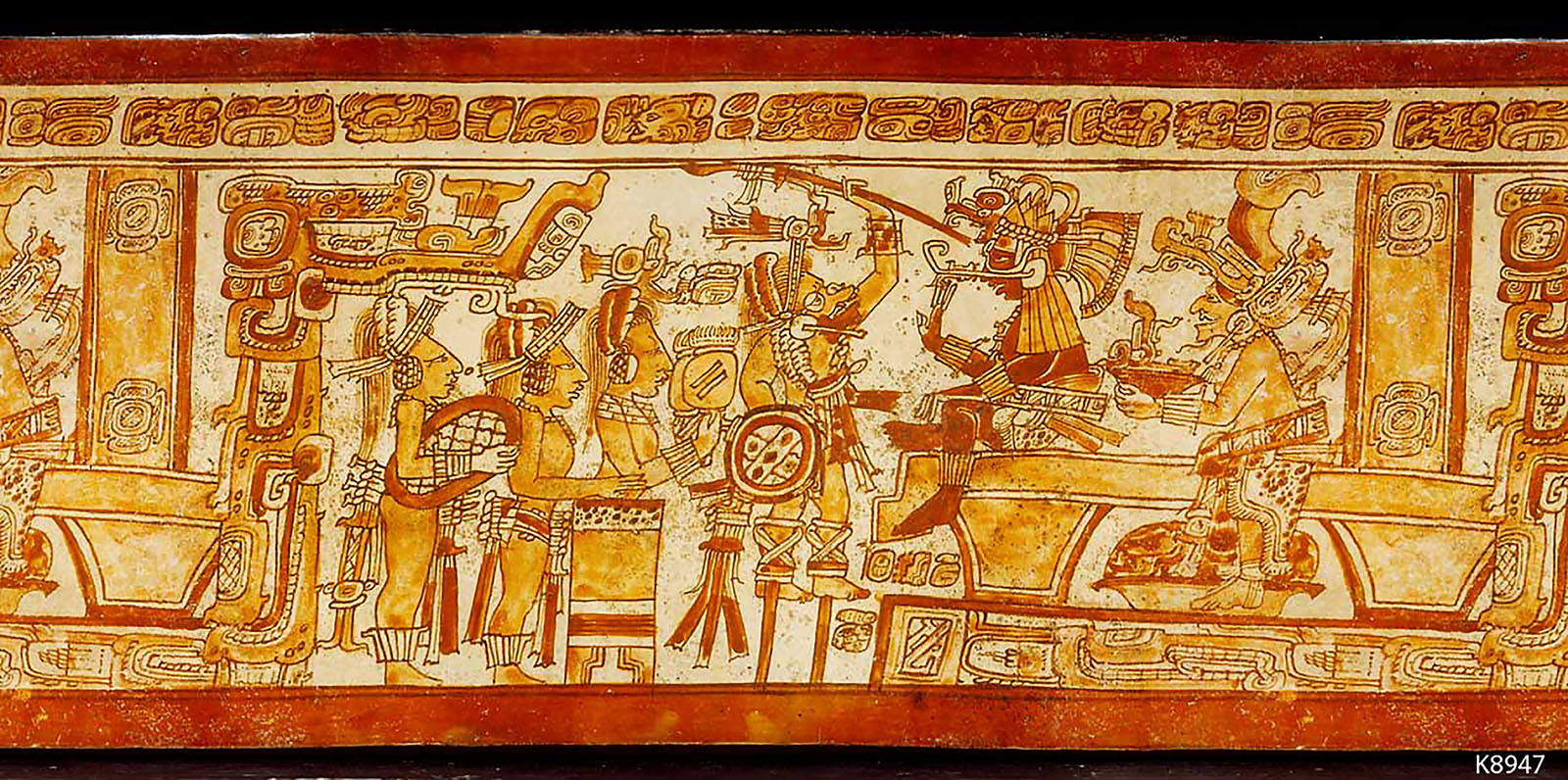

Elites engage in a ball game ritual. The ball (with a glyph inside) is about to connect with the king’s hip and chest deflectors. The horizontal lines are the ball court steps. Black body paint was often worn by warriors. Here, they are warring against the forces of evil. On the murals at Bonampak, bird headdresses were worn by winners; deer was worn by the losers. (Rollout photo courtesy of Justin Kerr)

Royal Players

It was a badge of honor for royalty to be good ball players. It’s reported that after great battles were waged, prisoners were brought back to the city of the victor where they were starved and dragged onto the ball court for a match. With depleted strength, they lost the game—and their heads—but shedding their blood on the court meant dying with honor. One writer suggests “The highest goal of Classic kings seems to have been to capture the ruler of a rival city in battle, torture and humiliate him (sometimes for years), then, following a ball game decapitate him.

Another says, “To capture an enemy and then let him be defeated in the ball game was to let him die with dignity. Royals became apotheosized—made divine—in this way. And the winner captured the loser’s power (the head was seen as the center of power).”

The Ball Itself

Ol, the Maya word for “rubber” is also the word for “heart” and “motion.” The ball was referred to as cahuchu “weaping wood” because of it was made from the sap of a tree. Inscriptions give the size of the ball, for instance, a circumference of “twelve-handspans” is indicated on a vase from Motul de San Jose in Belize. That meant it could be 12-18 inches in diameter. Spaniards also reported that the balls weighed six to eight pounds. And the juice of Morning Glory vine s were added to give them more bounce.

Later on, The Ritual Was Played As A Game

The object was to keep the ball in the air without touching it with the hands. Only shoulders, forearms, hips and knees could contact the ball. A goal was scored when the ball bounced off the wall and hit one of the stone markers—or a macaw head at Copan. If it ever went through a ring mounted on the walls—as at Chichen Itza—the person who did it won automatically. Scoring was based on faults: touching the ball with head or hands or feet; failing to connect with the ball; sending the ball out of the court. After one bounce, the other player got to serve the ball. If it bounced twice the other person scored. The first person to reach thirteen points won.

The Mesoamerican ball game provided a formalized context and ritual wherein the mystery of death and the mythology of creation could be repeated and celebrated with an eye to the future. As a contest between the forces of good and evil, arranged so the good—perceived as the Sun god—would prevail and the world would not end.

Game Played Between Brothers To Determine The Heir To The Throne

Excerpt from the novel, Jaguar Rising (p. 411)

(In the following, Fire Eyes Jaguar, the protagonist, surrenders his body to Lord K’in, the Sun god by taking a hallucinogenic drug and dawning a Sun god helmet. His brother, Flint Axe Macaw, does likewise wearing the helmet of Chaak Ek’, god of Venus. In this particular game, the winner (god representative) who has thirteen human skulls set on the wall—each representing a point—at the end of the game will replace their father as the Lord of Kaminaljuyu. “Dark Sun” is a reference to the ball).

AS HAD BEEN ESTABLISHED IN THE SKY—CHAAK EK’, GOD OF the morning star preceded Lord K’in, the sun god, along the White Flower Way— my brother danced onto the alleyway making quick turns, swinging his invisible axe and pounding the ground with his feet to taunt the lords of the Underworld. I waited for him to make a full circle, then followed behind him. Since Lord K’in was believed to prowl at night as a jaguar, I danced him as Red Paw had in Father’s courtyard the night after my presentation. I strutted, crouched and eyed Chaak Ek’ as if he were my prey.

The veil of brightness over my eyes burned even more because of the hundreds of torches that surrounded us. I poked my fingers through the eyeholes to rub them, but it didn’t remove the veil or ease the burning. Watching my brother dance, I had the feeling that I’d done this before.

Lightning flashed and a thunderclap shook the ground. I’d never heard anything so loud, not even in the House of Obsidian. I and everyone I could see had crouched. Just as suddenly, the light tapping on my helmet turned to pounding rain which quickly seeped into the eye- and mouth-holes. Oddly, the padding in my helmet was colder than the rain on my shoulders. My brother danced as if he welcomed it, running the alleyway like a freed deer, turning and leaping over the markers and darting back and forth to the end zones.

Feeling the power of the cheering, I danced jaguar staring, sprinting and pouncing but missing his prey. There came another bright flash and three breaths later a thunderclap so loud I yelled into my helmet. “Ayaahh! Huracan! First Lightning! Here we are! Do you see?” I crouched and stayed still. “Great Thunderbolt! Is this your doing? I said I would have the head of the Iguana. If Lord Tapir and the Iguana are the cloud of death, I will be the destroyer, the cloud breaker. But enough of this rain! Enough of this dancing. Father wants a ball game. Let us begin.”

Chaak Ek’ took a position on the northern side of the center marker, facing the eastern end zone with his hands on his knees. Facing him ten paces away, I took my stance. Keeper of the Ball went to the eastern marker where he held Dark Sun low, between his knees with both hands. To distract me from the pounding on my helmet, I kept repeating out loud, “Thirteen skulls, thirteen skulls, thirteen…” With my eyes trained on the menacing face of Chaak Ek’, words came into my head that shocked me. “Flint Axe, you are standing in the way of my destiny.” It was then that I knew—Lord K’in had entered my body, taken my place. I would never have had such a thought. Where Fire Eyes Jaguar had gone I did not know.

AS HAD HAPPENED IN THE MAKING OF THE WORLD ON the first day, the game began with the rising of Dark Sun from the east. Ballplayers referred to the opening volley as “Comes the dawning.” Chaak Ek’ got under the ball and deflected it off his hip. It bounced toward me. I turned and connected hard with my hip and the ball went out of his reach. It bounced once and rolled across the alleyway. I let out a yelp when the keeper of the count set a white skull on the northern wall.

As the keeper took his stance at the eastern end zone, the rain let up. He didn’t squat very low this time. The ball fell short. I deflected it off my hip and it went low. After one bounce Chaak Ek’ slid under it and connected on the underside of both wrists. I ran and connected high on my hip protector. The impact sent a sharp pain through my ribs, reminding me of Gourd Scorpion and the injury sustained in the Nine Step court. The ball bounced twice before Chaak Ek’ could get to it, so I gained another skull.

On the next round, the onlookers applauded our keeping the ball in play, back and forth without any misses. I tried to keep it high. Chaak Ek’ kept it low, apparently to take advantage of my injured leg. He made an elbow deflection and when the ball hit the ground it rolled. That put a yellow skull on his wall.

Chaak Ek’ connected with a stylish combination of a lunge and hip deflection. I returned it the same way and the onlookers applauded—even more, when he deflected with his knee and the ball rolled between my legs. Another skull for him.

The keeper squatted and turned his back to us. Chaak Ek’ went back and I stayed close. The ball fell short and I connected with both wrists. Chaak Ek’ got under it and butted the ball with his helmet, sending me running. I wasn’t even close.

Spectators in the end zone behind Chaak Ek’ were all a blur. The ball came to him and he connected with a stylish standing twist. I returned it off my hip. He deflected it back and we closed the gap between us. He turned and did a front deflection. On my return, he jumped back and connected with his knee-protector. I dove but missed.

I scored on the next round. Chaak Ek’ took the following two. He was managing better than me to either send the ball where I wasn’t or to hit it so forcefully I couldn’t get to it in time to connect. He was ahead of me by three skulls, but I was learning fast. By playing closer—which he seemed to want—and trusting the nubs on my sandals, I defeated him twice.

Hoping to slow me down, Chaak Ek’ kept deflecting the ball toward the center where the rain was pooling. I wasn’t slipping, so I played close to the marker and kept him on the sides. On a quick turn, he slipped and fell and the ball ran along the northern platform. When he slipped and missed again, I counted the skulls—Lord K’in seven, Chaak Ek’ six.

____________________________________________________________________________

For a brief description of The Path Of The Jaguar novels: Go to the Home Page—Novels

Links To Amazon.com for paperback books and Kindle Editions

Jaguar Rising: A novel of the Preclassic Maya

Jaguar Wind And Waves: A novel of the Early Classic Maya

Jaguar Sun: The Journey of an Ancient Maya Storyteller

Ancient Maya Clothing

What you wore was a sign of who you were and where you lived

Whether intended or not, clothing communicates. For example, an apron in modern society can signal that the wearer is a chef or manual laborer. It can also symbolize the wearer’s beliefs and values, as when an apron is worn by a Rabbi. The elite Maya of the Classic Period went to extremes in the latter category, investing many items of clothing with meaning.

While commoner garments were simply intended to beautify or eroticize the body, those depicted in art—ceremonial regalia, jewelry and body manipulation such as scarification, tattooing, piercing, teeth filing and cranial modification, were rich with meanings that referenced and celebrated their myths and ideology. In the Early Preclassic period, symbols were largely based on ancestor veneration. In the Classic Period, belief systems evolved to where the emphasis was on stories of creation, gods and apotheosized rulers—those who’d died and became deified.

With regard to body coverings, the materials at hand were mostly plant fibers including cotton, kapok, yucca and agave, which contains henequen and maguey fibers. Animal products such as duck and goose feathers, deer hides and feline furs were incorporated as well. A thousand years later, in Aztec Mexico, only the king could wear fine mantles of cotton. So it’s likely that cotton was also reserved for Maya elites. With regard to commoners and slaves, very little is known about their coverings, except they mostly consisted of maguey fibers. Soaking and cooking the leaves made them tender enough to scrape and shape into long soft threads that were dried in the sun and then woven into fabrics.

The principle device for weaving raw fiber into cloth was the backstrap loom, similar to the ones used today. Since the looms are not very wide, several widths of woven cloth were sewn together to create square or rectangular shaped garments. These were fitted in place with a belt or fabric tie. Weaving lent itself to the making of geometric shapes and patterns. Below, the patterns woven into the woman’s huipil and the ruler’s cape symbolize the four cardinal directions.

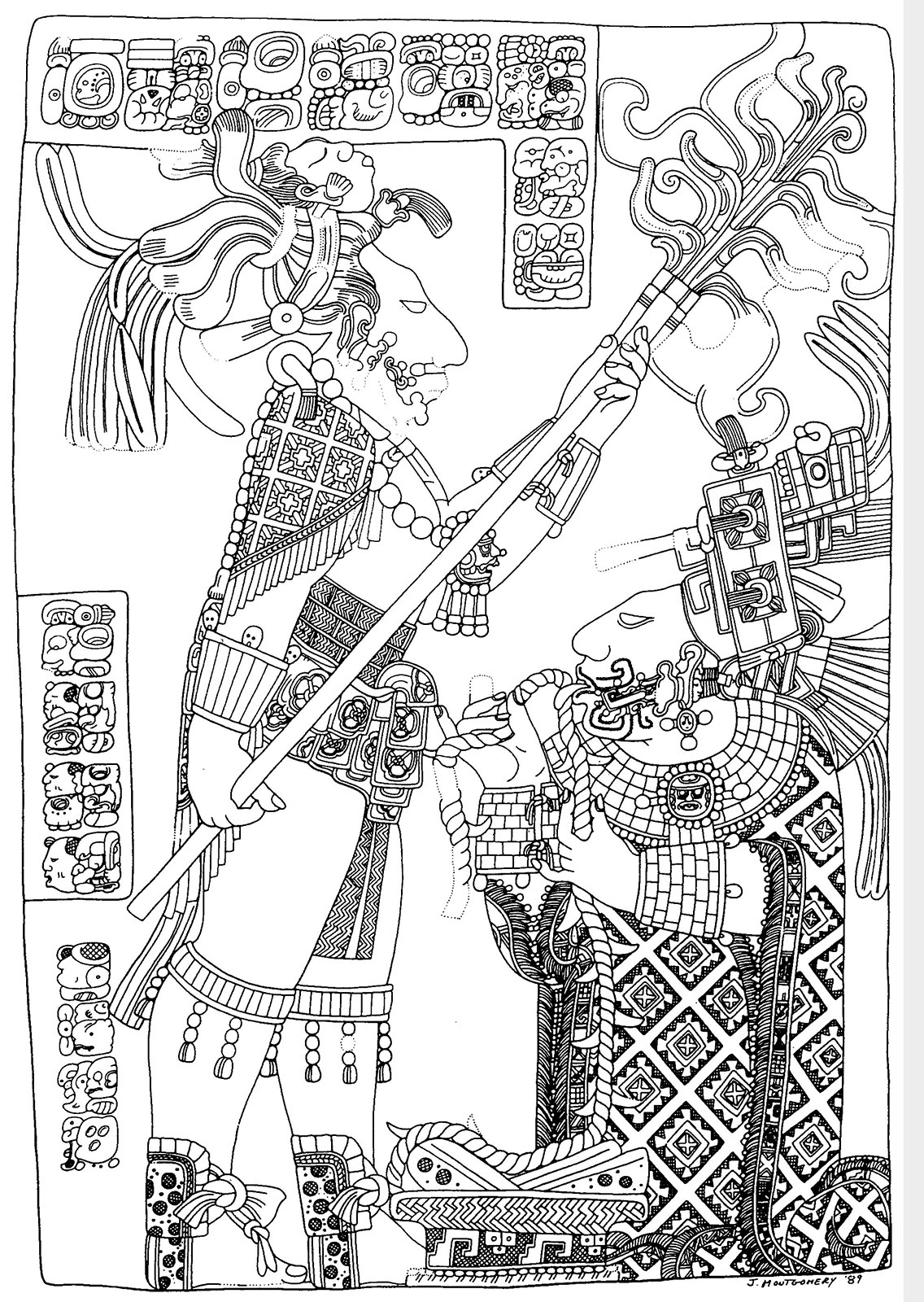

Dated approximately 709 AD, Shield Jaguar, Lord of Yaxchilan, holds a torch over his wife, Lady Xoc, who performs a bloodletting sacrifice by pulling a barbed cord through her tongue. Her huipil appears to be embroidered and trimmed with fringe and pearls, and the pectoral on her beaded collar—likely made of shell or jade plaques—depicts the sun god. The object at their feet is an offering bowl containing blood-splattered cloths to be burned along with copal incense.

Although insect, vegetable and mineral dyes were traded extensively in the Classic Period, the archaeological record indicates a strong preference for painting on cloth—clothing—using stamps and brushes. Embroidered stitching, which was an easy and quick way to embellish a woven garment with color and designs is also in evidence, worn by elite women. Though scholars are still debating gender roles and responsibilities, weaving tended to be the domain of women, and farming the responsibility of men. Attire for both men and women varied depending on the individual, status, location and time period.

In this unprovenanced panel in the Cleveland Museum of Art dated 795 AD, a royal woman holds an effigy, a “God K” or “K’awiil scepter.” The kings who displayed it proclaimed themselves masters of the “Vision Serpent,” which conferred upon him the ability to negotiate with the gods. Here, the woman is wearing a huipil, a long outer garment that covered the shoulders, chest and hips. Those worn by commoners were likely plain with little or no embellishment. Huipils of elite and royal women usually contained symbols. The four quatrefoil designs on this figure represent “portals” to the otherworlds. Also evident here is an undergarment. In hot climates, women of all ranks more often wore a sarong, a long garment tied under the arms that could more or less conceal the legs (See the figurine on the right in the first photo).

The figurine in the center wears a typical loincloth. Men of all ranks wore them, some with shorter or longer hanging ends, a long or short skirt, a short waist-length jacket and in some instances the elites wore a short cape. Because males depicted on monuments are sometimes shown wearing long skirts as seen on Copan Stela H (Schele #1011), it took the decipherment of inscriptions for scholars to realize they were men. The length of a skirt alone is no longer considered an indication of gender.

Piedras Negras Stela 8

Piedras Negras Stela 8

The jade-beaded latticework on a cape or skirt, seen here, can be long or short, worn by a man or woman. Always, it signifies maize god. Commonly, a Spondylus (spiny oyster) shell hangs from the belt with the face of a fish on it, a mythological shark the maize god defeated in the Underworld. It was worn as a sign of victory. That beaded garments are worn by both men and women, anthropologist Karen Bassie-Sweet sees them as an example of gender “complementarity.” Maize plants, and therefore the maize god, had both male and female elements.

Lavish clothing, regalia and costumes signified elite status. Fabric embellishments could include jaguar pelts, bird feathers, flowers and wood, leather or thinly painted ceramic constructions that represented fish, waterlilies, the heads of gods, underworld monsters and other mythical or symbolic creatures. At the other end of the spectrum, because nudity signaled disgrace, captives wore nothing other than strands of paper in their earlobes, another symbol of disgrace.

The elaboration of footwear was another element that distinguished the elite from commoners. Slaves went barefoot. Most everyone else wore sandals. I notice, however, the royal woman wearing the decorated huipil in the above drawing is barefoot. Most unusual. Kings always wore high-backed and probably animal hide sandals, often embellished with feathers and jewels containing symbols. On Yaxchilan Lintel 24 (above), the king’s sandals display black circles with hashing that represented little jaguar pelts.

Reference to Backstrap Looms

Excerpts from the novel, Jaguar Rising (pgs. 31 and 223)

Thunder Flute interrupted. “Of all the places we trade, none offers better embroidery. On the last trip, the exchange was better here than at Kaminaljuyu. Lord Macaw gives his son an advantage—and we take it.”

“All the women weave,” Pech said. “You will see—as soon as a flower can talk she will be sitting beside her mother at the loom. Unfortunately for us, the women at court do the best work. Most of it never reaches the marketplace. If I or one of the assistants is not nearby, do your best. Better to acquire fine work than not. You will know it when you see it.”

The steward led us across the plaza to a large house that sat on a high, white-painted platform with scarlet macaws in flight painted on both sides of a broad stairway. He told us his master was holding council, but he went in anyway to let him know that we were there. While we waited, Standing Rock led us to the corner of the platform that overlooked a patio where women were weaving with back-strap looms. Thunder Flute spoke from behind me and close to my ear. “Ladies of the court. They weave from dreams. The cotton is the finest you will see anywhere.” Voices behind us were three men in red robes coming through the doorway. They nodded to us and went down the steps.

Ruler Wears The Beaded Maize God Skirt

Excerpt from the novel, Jaguar Rising (p. 360)

Moments later, Lord Cormorant, lavishly attired in quetzal feathers and a jade-studded skirt, came down the steps with his jaguar prophet. Stopping on the first terrace, the prophet replaced the ruler’s k’atun helmet with the sak huunal. The prophet raised his arms and the drums called us to order. I judged there to be near to six hundred people there, all huddled in blankets. After several moments of silence, looking to the sky with arms outstretched, he gave the prophecy for the next twenty years.

A Gift Of Elite Sandals To A Merchant

Excerpt from the novel, Jaguar Rising (p. 315)

BLOOD SHARK HAD THE SERVANTS MOVE MY ITEMS TO THE side and he gestured for me to follow. Blue Skin stepped down from the dais and Yellow Stone admitted other servants with bundles intended for Thunder Flute as he came over. “Thunder Flute Rabbit,” the lord said gesturing, “Your compensations for teaching Blue Skin and our first spears the ways of the Tollan warriors.”

The largest bundle contained a tapir pelt and seven embroidered mantles, beautiful pieces for Thunder Flute’s wearing. Next, came an assortment of colorful feathers which Blue Skin named: turkey, eagle, toucan, duck and owl. The great white heron feathers were especially beautiful, but it was the owl feathers that Thunder Flute chose to touch with two fingers and express his gratitude. From a third bundle, he held up a pair of high-backed sandals. “The bottoms and straps are crocodile,” Blue Skin said. “The backs are doe-hide. Very soft.” Owl faces were burnt into both backs. When he put them on and walked, Thunder Flute’s face lit up like never before.

“For when you become raised and titled,” Lord Tapir explained. “The burner tried to match the tattoo on your chest.”

* All drawings courtesy of The Montgomery Drawings Collection, 2000. FAMSI Resources.

____________________________________________________________________________

For a brief description of The Path Of The Jaguar novels: Go to the Home Page—Novels

Links To Amazon.com for paperback books and Kindle Editions—

Jaguar Rising: A novel of the Preclassic Maya

K’awiil: The Ancient Maya Lightning Lord

God of fertility, abundance and royal lineage

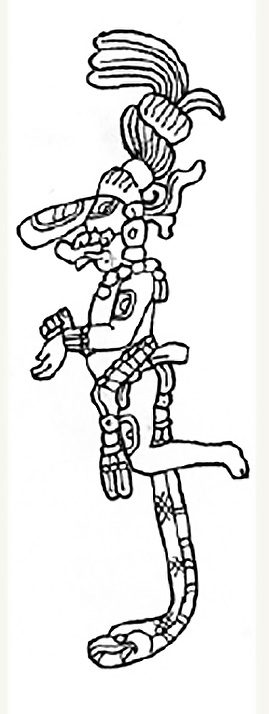

In Maya art, K’awill often appears in the form of a scepter that, when held, signifies royal lineage. Because one of his legs terminates in a serpent’s head, the Popol Vuh—the sacred book of the K’iché Maya—identifies him as Cacula Huracan, “Lightning One-Leg.”

His forehead is a mirror penetrated by a smoking axe, which references ancestors and designates him as a lightning lord. The hooks in his eyes securely identify him as a deity.

In Classic times, at accession events, when the kings displayed the K’awiil scepter they proclaimed themselves masters of the “vision serpent,” the ability to manifest benefits for this world from other world sources. The idea was that K’awiil cast down serpentine lightning to make the connection between the sky and earth, showering the divine seed of the ancestors upon his descendant, the current ruler.

The scepter was made of wood and was carried in the right hand, except when that hand was needed for scattering blood or maize kernels during rituals.

K’awiil Scepter. Drawing by Linda Schele © David Schele

Mythically K’awiil was the third born son of First Mother and First Father, the Maize God, born on the day Hun Ahaw, “One Lord.”

His brothers were the Hero Twins, and he was linked to the forces of fertility. To show his association with abundance, his upturned nose was depicted as maize foliage. In some depictions he carries sack of maize and cacao beans, further associating him with agricultural abundance.

Through him, revelations were made. And through his lightning-serpent strikes, human souls were transformed into shamans or “true men.”

There’s also speculation that he may originally have been the personification of the axe that Chahk, the rain and storm god, used to crack open the shell of Great Turtle—the earth—allowing the Maize God to ascend from the Underworld so he could deliver abundance to the world.

Drawing courtesy of Schele, Linda. Linda Schele Drawings Collection. 2000. 11-18-19. FAMSI.<http://research.famsi.org/schele_list.php?rowstart=15&search=k%27awiil&num_pages=4&title=Schele%20Drawing%20Collection&tab=schele>

The above drawing was made from four identical, wood and stucco-covered statues of K’awiil found in Burial 195 at Tikal.

Lady Jaguar Paw, Custodian Of The K’awiil Scepter

Excerpt from the novel, “Jaguar Wind and Waves” (p. 13 )

Between my sister and me, I was the fearless one, more determined than my brothers to have my way and make Father proud. It wasn’t until he sent me to Tollan in fulfillment of his alliance with the lords there, that I took the title I came to share with my husband, Spearthrower Owl. When they raised him to “Supreme Anointer, Land of the Quetzal People,” they made us both, together, custodians of K’awiil, the lightning god who conveyed the authority to rule. From then on, because it fell to me to serve as the custodian of the living K’awiil scepter, I was sometimes introduced as Lady Jaguar Paw, Custodian of K’awiil.” I didn’t know it then, but that title—and the office and rituals that came with it—gave birth to the dark clouds that would grow into the thunderhead that took me down.

Presentation Of The K’awiil Scepter

Excerpt From Jaguar Wind and Waves (p. 74-76 )

In silence but with soft drumming, Spearthrower returned to his place and Fire-born came forward. As he gave his speech, I followed Banded Snake up the steps and across the way to the shrine that housed the god bundle. He took my headdress and replaced it with a red, serpent-coil turban. Keeper of the Bundle was inside waiting for me. He had the K’awiil scepter ready, sitting on his red pillow with the serpent leg dangling over the front.

Following the ritual I was taught at Tollan, I chanted the little god’s honorifics and passed two fingers, the sign of acceptance, across the blue-painted wood, front and back to insure that everything was as it should be—the feathers securely tied and rising high in his headdress, the obsidian axe-head firmly attached to his forehead, pearl wrist cuffs and anklets in place, the beaded jade necklace centered on his chest and the belt ornaments centered between his thighs.

Last to be inspected, was the little ceramic bowl that fitted into a cavity behind and at the bottom of his skull. Spearthrower always took it out and inspected it the night before an anointing, but he left it to me to push a brush through the cavity and channels that led from the bowl to his mouth and forehead to insure they were not obstructed. With that done I stepped aside so the keeper could put in a nodule of burning coal, which I then dusted with little beads of copal incense. With the skull panel replaced, the “precious breath” came out his mouth and the slit behind the axe that rested high on his forehead.

While I waited with the breathing K’awiil, Banded Snake went down the steps and nodded to Spearthrower. He nodded to Fire-born and and he concluded his talk. “Now it falls to you!” he said. “The k’in has come for you to show the gods that we are one people, no longer Tollanos and Maya. We are Tikal!” Again, the Tollanos applauded and the Maya remained silent.

Trumpeters standing atop the steps on both sides of the plaza raised their wooden horns and sounded a loud and prolonged call to announce the coming of Lord K’awiil. Holding the little god in front of me with sweet incense coming out his mouth and forehead, made it difficult for me to see at times. Even with Banded Snake steading me to the side with his arm, I took the steps slowly. Those who were not already on their knees knelt as Spearthrower, doing his best to talk louder, introduced K’awiil as a lightning lord and patron of rulers—the sky god who authorizes rulers to speak to, and on behalf of, the Makers.

Spearthrower spoke rightly when he proclaimed that it was a day to be remembered. So many important things happened that day—he presented himself to the people of Tikal as the supreme prophet of Tollan, son and voice of the goddess, First Crocodile took the K’awiil anointing and was thereby authorized to carry the title, “Succession Lord,” K’awiil authorized Fire-born to serve as Regent until First Crocodile was ready to rule, and by having all this witnessed by the new ministers, Spearthrower established himself as the lowland kaloomte’, supreme authority. Sadly, it also marked the day when my people stopped resisting.

____________________________________________________________________________

For a brief description of The Path Of The Jaguar novels: Go to the Home Page—Novels

Links To Amazon.com for paperback books and Kindle Editions

Jaguar Rising: A novel of the Preclassic Maya

Dowsing and Divination

Are there underground forces that can be felt?

My guide at Xunantunich, Belize

My guide at Xunantunich, Belize

Dowsing is a type of divination, typically used today to locate ground water, buried metals, gemstones, oil and grave sites without the use of scientific instruments. It’s consider a pseudoscience because there’s no scientific evidence that the technique is any more effective than random chance; skeptics say the dowsing rod moves due to accidental or involuntary movements of the person using it. The entry in Wikipedia says it probably originated in Germany in the 16th century.

I never thought much about it. Then I experienced it first hand. My guide at Xunantunich told how the ancients used dowsing as well as heavenly bodies to orient their temples and palaces. Perhaps reading my doubting expression, he went to a tree, cut off a branch and shaped it into the “rod” pictured above with his pocket knife. He specified that the rod had to be cut from a green “living” branch.

Crossing back and forth over the central axis of the plaza, the rod dipped strongly at what he said was the center line of the site. When I asked if I could try it, he said “Gringos can’t do it.” He had often had non-native people try it and it never worked for them. Still, I wanted to try it.

The guide was as nonplussed as I was when it worked for me, so he gave me a test. With my eyes closed, he turned me around several times and then led me by the hand in a random course of maybe thirty yards. With my eyes still closed, I walked forward without any guidance for about twenty feet.

Suddenly, the rod pulled down. Hard. I resisted, but the only way I could get it to raise was by walking away. Back and forth I went. Even at different distances, I got the same result, always with my eyes closed. Each time, when the rod bent down I was somewhere along the invisible centerline of the plaza, aligned to the center of pyramids about a football field apart. The guide was amazed. “I never seen nothin’ like it!” he said.

He thought that might have been an anomaly, so we tried it again at another location and got the same result—the rod pointed down forcefully wherever there was an eye-line (called a “ley-line”) between distant temples and palaces.

I came away a believer—that in addition to making structural alignments relative to the position of the sun, moon and stars, the ancients may have also used dowsing rods to discover ley-lines. Because alignments maintained “as above, so below” order, they may have even located their early settlements and cities along these lines. Normally, when I toured Maya sites I wore my “science hat.” But there were instances like this when I was challenged to keep an open mind.

Dowsing At Xunantunich

Excerpt From “Jaguar Sun” (p. 247-248 )

“I told him about your apprenticeship with the K’uhuuntak. He wants to see if you have powers.”

“What kind of powers?”

My brother continued. “Some people have the gift of locating spirit forces—lines in the underworld made by the gods when they ordered the world. Have you heard of them?” I hadn’t. “He calls them ‘footprints of the gods.’ The man who he engages to find them lives three days from here, so he is always looking for someone who has that gift. He liked what you did with the chert. Just play along.”

“What do the lines look like?”

“They are felt, not seen. Xunantunich is a pilgrimage center because there are so many of them here. Everything you see, every structure here, is aligned with those footprints. ”

Knows Best stopped short of the middle of the plaza. He had me cover my eyes with both hands and then he turned me around three times. “Now,” he said. “Keep one hand over your eyes so you cannot see, and point with the other to the place where Lord K’in will make his descent.” There was no trick to it. Because of the heat on my face, it took only a moment to point west.

“Did the K’uhuuntak teach you that?”

I told him about the heat on my face, but I didn’t tell him I was in the habit of turning to face the sun as a general rule—something I learned from the K’uhuuntak. Even as an apprentice, I just naturally aligned myself with the center of things, near and far. At Dos Pilas I was most comfortable sitting in the center of the cage—except when I was sleeping or when there was a commotion.

Knows Best had me take hold of the “handles” of the branch he’d stripped so the longest part pointed away of me. “Walk out,” he said. “Point the stick straight ahead. Grip it tight.” I started to walk. “Look ahead, not at the stick.” To my right, there was the high temple with its gleaming headband. Opposite, well down the plaza was the palace. “Slowly!” Knows Best shouted.

Ayaahh, this is ridiculous.

Suddenly, I felt a tug on the end of the stick, so I pulled it up. “Hold it tighter,” the man said. Three more steps and the branch pointed to the ground so forcefully the arms of the branch twisted in my grip. I resisted, but it was difficult.

“Step back three paces,” Knows Best said. When I did, the tugging on the branch relaxed. I stepped forward again, and again it was like an invisible hand had grabbed hold of the stick and was pulling it down. “Continue on now.” Within four steps, the tugging eased and then stopped. Looking, I was standing on the north-south centerline between the temple and the palace.

Almost on a run, we followed Knows Best to the temple. On the upper terrace—apparently, following him was all the permission I needed—we walked around to the eastern side where he had me hold out the branch and walk south to north. At the mid-point of the temple, I felt the tug again and the stick pointed down—hard. At the front of the temple, Obsidian pointed to the palace in the distance. “Five hundred and twenty paces,” he said. “I walked it off.” Within a few steps of walking east to west the stick pointed down again and I couldn’t pull it up.

“I do not understand,” I said to Knows Best. “What is doing that? What does it mean?”

“It means you have a special power. We will talk later.”

Special power? That was what Sharp Tooth, the healer, had said about my being raised up. So this is my special power?

____________________________________________________________________________

For a brief description of The Path Of The Jaguar novels: Go to the Home Page—Novels

Links To Amazon.com for paperback books and Kindle Editions

Jaguar Rising: A novel of the Preclassic Maya

Kakaw (Chocolate)

A highly valued trading commodity, and an elite beverage

Kakaw trees can’t tolerate high altitudes or temperatures below 60º F. They need moisture year-round, so during prolonged dry seasons irrigation is necessary. Given these considerations, they were domesticated in the Pacific coastal plains of Guatemala and Chiapas around 1000 B.C., at the height of the Olmec civilization at San Lorenzo. The area around Izapa, a Late Formative site in Chiapas, was a particularly rich source of kakaw (cacao) because it was very hot with volcanic soil.

The variety of cacao grown in the Maya area is called theobroma bicolor—“pataxte” in Mayan. The tree’s flowers and fruits or pods grow directly on the trunk. Each fruit is around 11” long and 4” wide with an average weight of one pound. The color ranges from reddish to green, but it changes to yellowish orange as the fruit matures. The pods contain 20 to 40 beans enveloped in a sticky, white pulp. The beans are large and flat, and are sometimes eaten raw. Each tree will produce around 40 pods, yielding about 4.5 pounds of chocolate. It has been suggested that the name “chocolate” derives from the Mayan word chokola’j, “to drink cacao together.”

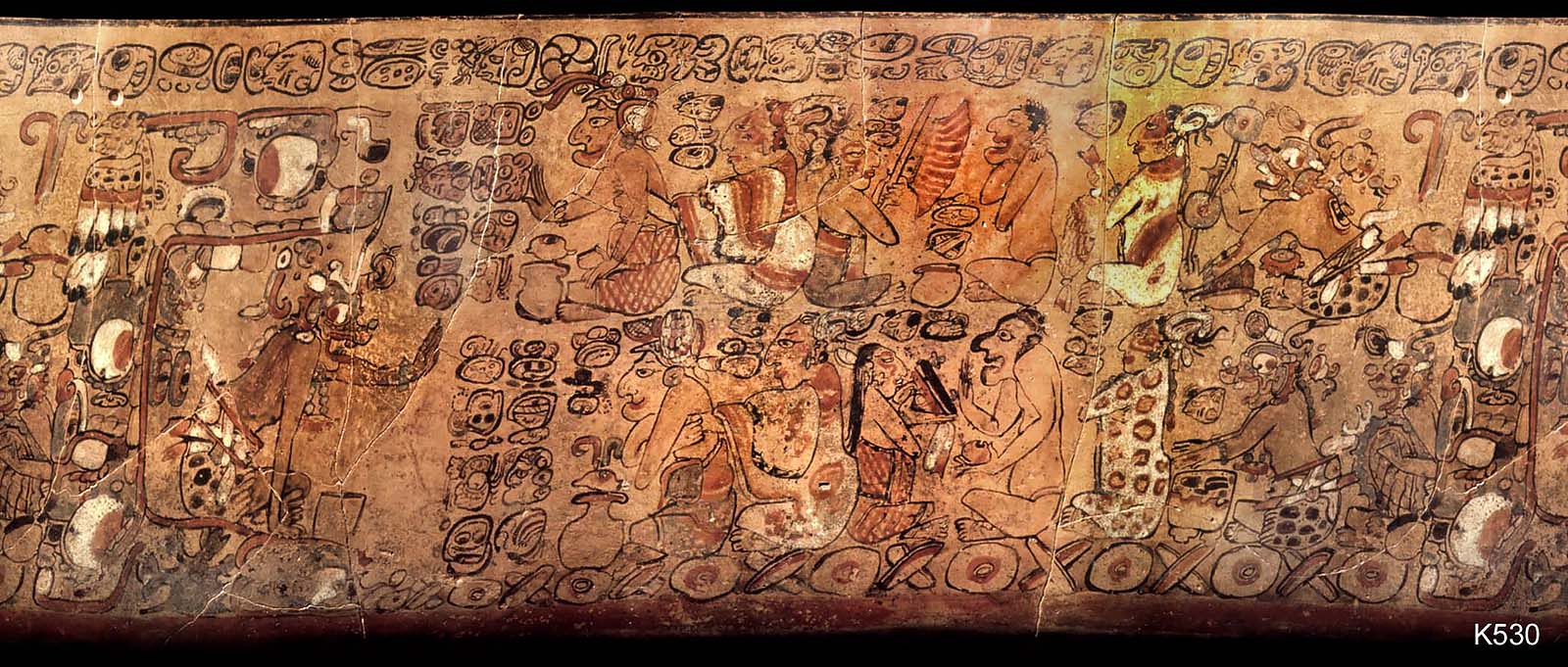

Mentioned frequently in the inscriptions as a trade good and an elite consumable, it seems kakaw was an array of beverages rather than a single drink. Beverages are described as “honeyed kakaw,” “flowered kakaw,” “bright red kakaw, “black kakaw,” “ripe kakaw,” “sweet kakaw,” and “frothy kakaw.” The ancients toasted the beans and used them to make gruels and porages. Additives could include honey, chile peppers, annatto (to make it red), fruit juices, flower blossoms and vanilla. And through fermentation, they produced a cacao flavored alcoholic beverage. Perhaps because kakaw concoctions were such an imported extravagance, some of the inscriptions specify the cities where and when they were served.

A palace scene from Dos Pilas, Guatemala shows a flower bouquet being presented to a seated lord. In front and below him is a platter of kakaw pods.

A study by Joanne Baron, published in Economic Anthropology, revealed that cacao beans, “originally valued for their use in status display, took on monetary functions within a context of expanding marketplaces among rival Maya kingdoms. These products would eventually go on to serve as universal currencies across the different Maya regions and were used to finance state activities as well as household needs. By the time the Spanish had arrived in the early 1500s, these (kakaw) products were being used to pay tribute or tax to leaders, to buy and sell goods at the marketplace or pay workers.”

The kakaw sacks shown in the Bonampak murals were labeled with the kakaw glyph surmounted by a number which David Stuart deciphered as 5 pik of forty thousand seeds. He also notes the frequent use of a 3 pik label—twenty-four thousand seeds—which coincides with a count of cacao seeds that was considered a “carga” in Postclassic highland Mexico.

At the time of the conquest, a “load” of kakaw—24,000 beans—was worth twice as much in Tenochtitlan as along the Gulf coast. A rabbit costs 10 beans, and a porter charged 20 beans for a short trip. A 1545 document written in Nahuatl states that a turkey was worth 200 cacao beans, a tamale worth one, and the daily wage of a porter at that time was 100 beans. It was also noted that dishonest traders made counterfeit beans by stripping the husks of the beans, filling them with sand, and mixing them with genuine beans. Careful customers squeezed each bean to test it.

Counting Kakaw Beans

Excerpt from Jaguar Rising (p. 205)

OUR EARLY TRAINING HAD TO DO WITH TRADING, TERRITORIES, the names of places, rulers, ministers and counting. We learned the value of goods, especially those desired by lords, noblemen and holy men. We learned hand signs, not only to trade and speak with foreigners but also to signal each other under conditions of scouting and attacking. We learned how to use vines, moss on the side of trees and the stars as directional pointers. Especially, we learned which goods would be traded in the various markets.

To learn how to show respect to power and speak in our trading partner’s favor, we put on hats and bargained with each other. Instead of using stones and sticks for counting, Pech taught us to use lucina shells for “zero,” kakaw beans for “one’s,” and flat hands for “five’s.” A hand covering our chins stood for “twenty.” In the counting trial, we had to place and call, sum and subtract numbers in orders of thousands because kakaw beans were traded in “loads”—cloth bundles of eight thousand, what one man could carry.

Kakaw Valuation

Excerpt from Jaguar Sun (p. 98)

BY THE THIRD DAY IN THE MARKETPLACE AT IXKUN, SO many warriors and farmers were coming to have me rework their cherts and flints, Eagle fixed the exchange at two, four or eight hundred kakaw beans depending on how long it took me to do the work. After another day, a line formed. I was spending nearly as much time counting kakaw and shell beads as I was shaping stone, so Eagle had one of the assistants do the counting for me. It felt good to be contributing to the expedition, but by the end of the day, the muscles in my chopping arm were chattering. And I was out of Strong Back. Darts came by several times and stopped to watch me work. Whenever I looked at him or nodded he turned away.

Checking For Counterfeit Beans

Excerpt from Jaguar Rising (p. 67)

In the days leading up to Grand Procession, the counters and court scribes examined every needle, bead, feather, hide and kakaw bean. Day and night, a band of guards walked the perimeter of the compound while others armed with spears, axes, knives and flint-tipped darts walked the patio. Two of them stationed at the stairway searched everyone who came and went, including those of us who lived on the compound.

Pouring Kakaw To Make Foam

Excerpt from Jaguar Wind and Waves (p. 67)

For the feast I had arranged for the ministers to sit on reed mats in a circle. Lime Sky and her assistants prepared maize leaf tamales, most stuffed with turkey, others with paca meat. Four of my serving women had never been to court before, so I worried that they would drop or spill something—or not understand a minister’s gesture. Along with the tamales we served roasted grubs with mashed beans and platters of cooked chayote greens topped with crumbled roasted squash seeds that she dusted with chili powder. For the beverage we served chih with lime juice and honey. The final offering, an extravagance usually reserved for lords and their ladies, was kakaw poured into tall cups from the height of the server’s breast to raise a dark brown foam.

(Photo of the palace scene courtesy of Justin Kerr “Maya Vase Database”)

____________________________________________________________________________

For a brief description of The Path Of The Jaguar novels: Go to the Home Page—Novels

Links To Amazon.com for paperback books and Kindle Editions

Jaguar Rising: A novel of the Preclassic Maya

Xibalba: The Place of Fright

The Maya underworld and the god of death

Rollout vase photo courtesy of Justin Kerr

Rollout vase photo courtesy of Justin Kerr

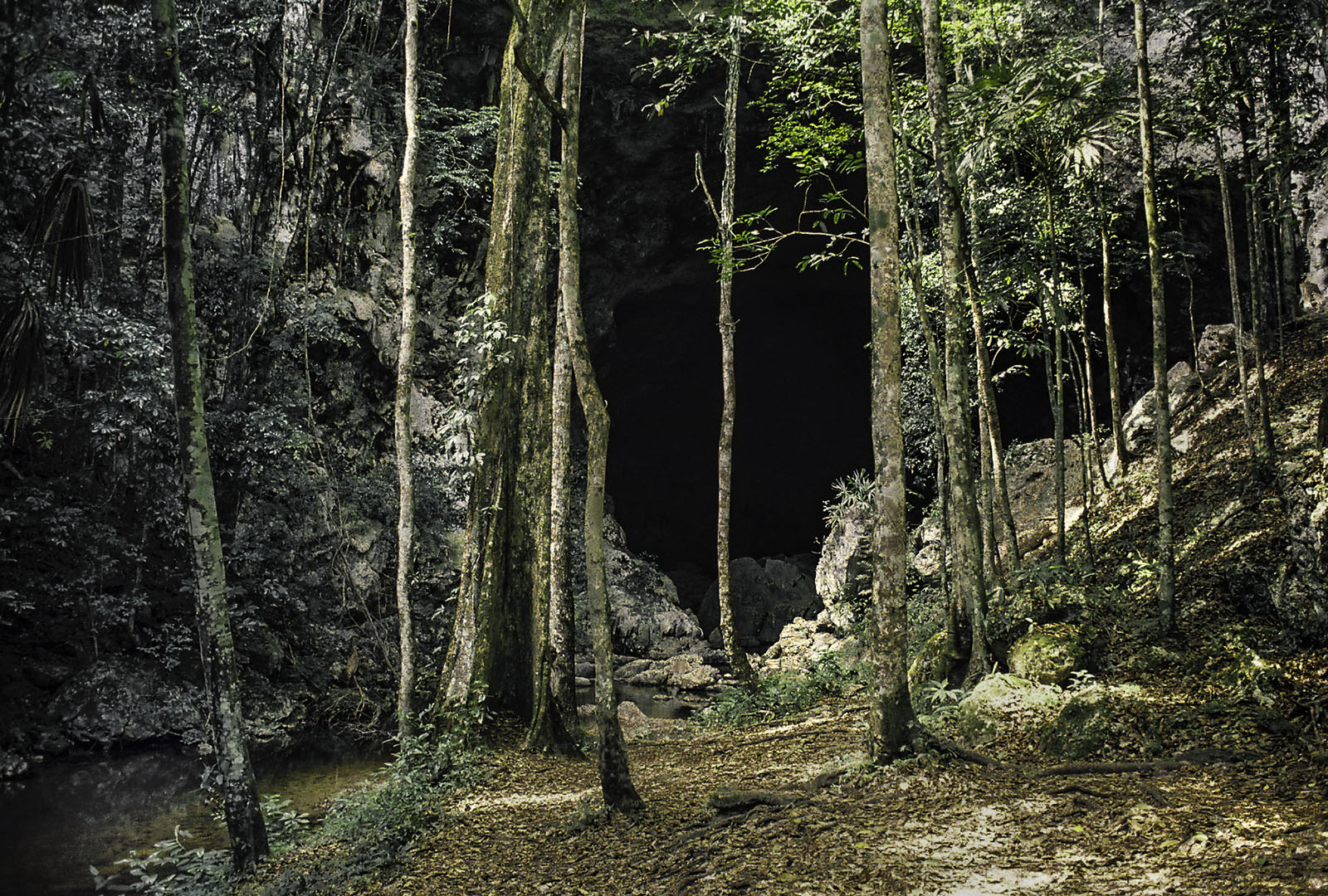

The Maya Underworld, called Xibalba (She-balba), “The Place of Fright,” was the realm beneath the surface of the Earth and under water, especially in caves. It was perceived to have nine descending levels arranged like an inverted pyramid, and was ruled by the Bolontik’u, “Nine Lords of Death” and was often depicted on vases as a giant conch or snail shell which enclosed a mysterious other reality interpreted by some to be an infinite, eternal and bloody ocean of bliss.

The Underworld was always pressing upward through portals—volcanoes, floods, and earthquakes—where the demons could emerge and work their dark magic. As entrances to the Underworld, caves were considered sacred and preferred locations for sacrificial offerings. There is no evidence to suggest that Xibalba was a kind of hell; the belief was that to die in one world was to be born into another.

The Lords Of Xibalba

According to the Popol Vuh, the K’iche’ Maya mythical “Book of Counsel,” the Lords of Xibalba possess three outstanding characteristics. In the first place, they were liars and tricksters. To trick the Hero Twins into playing a ball game, they said they admired their ability and the contest would be exciting. But it was just an enticement to kill them.

Secondly, the lords were stupid. In a second attempt to create human beings who would praise them and offer them their blood and sweat, they made them out of wood. There was nothing in these human’s equivalent to hearts or minds, and they had no memory. It was a failed attempt. Lastly, in several instances, the Underworld lords demonstrated cruelty and hardheartedness.

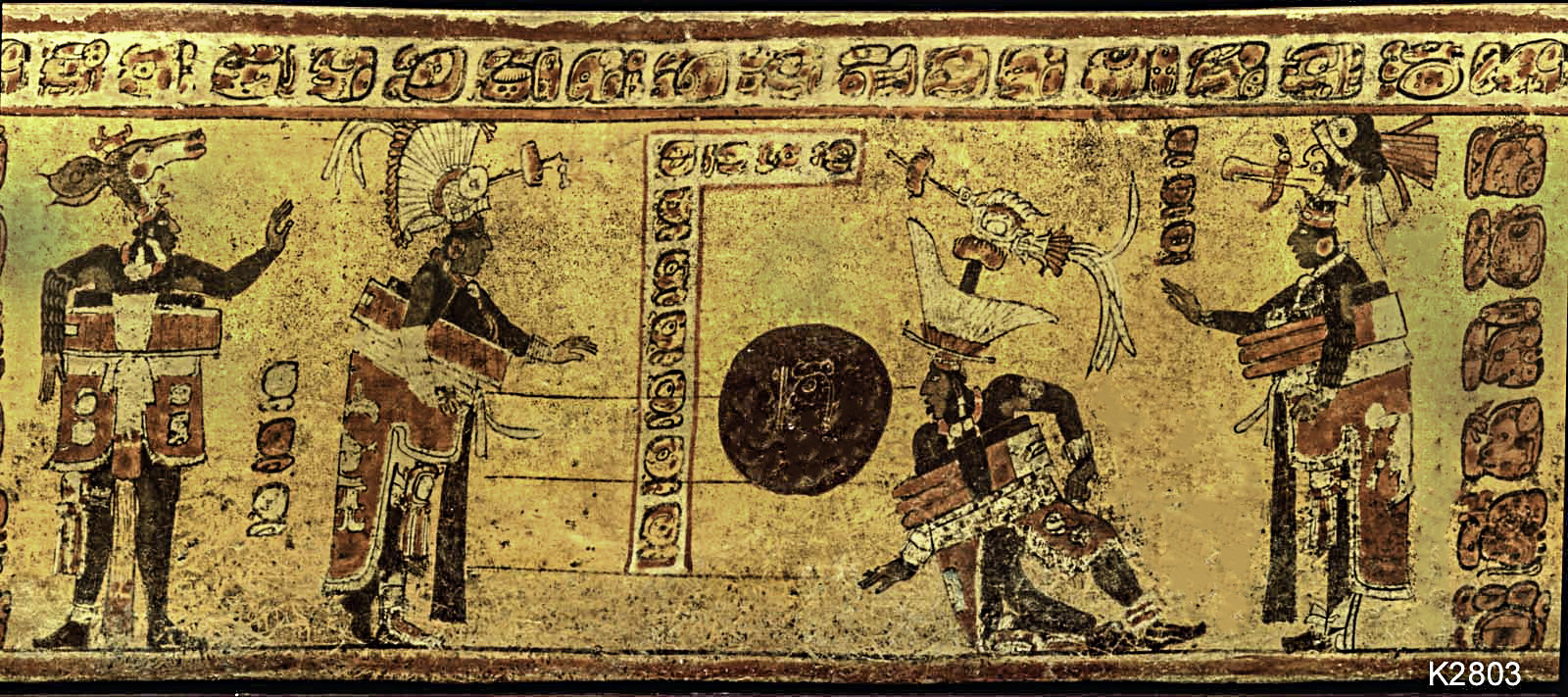

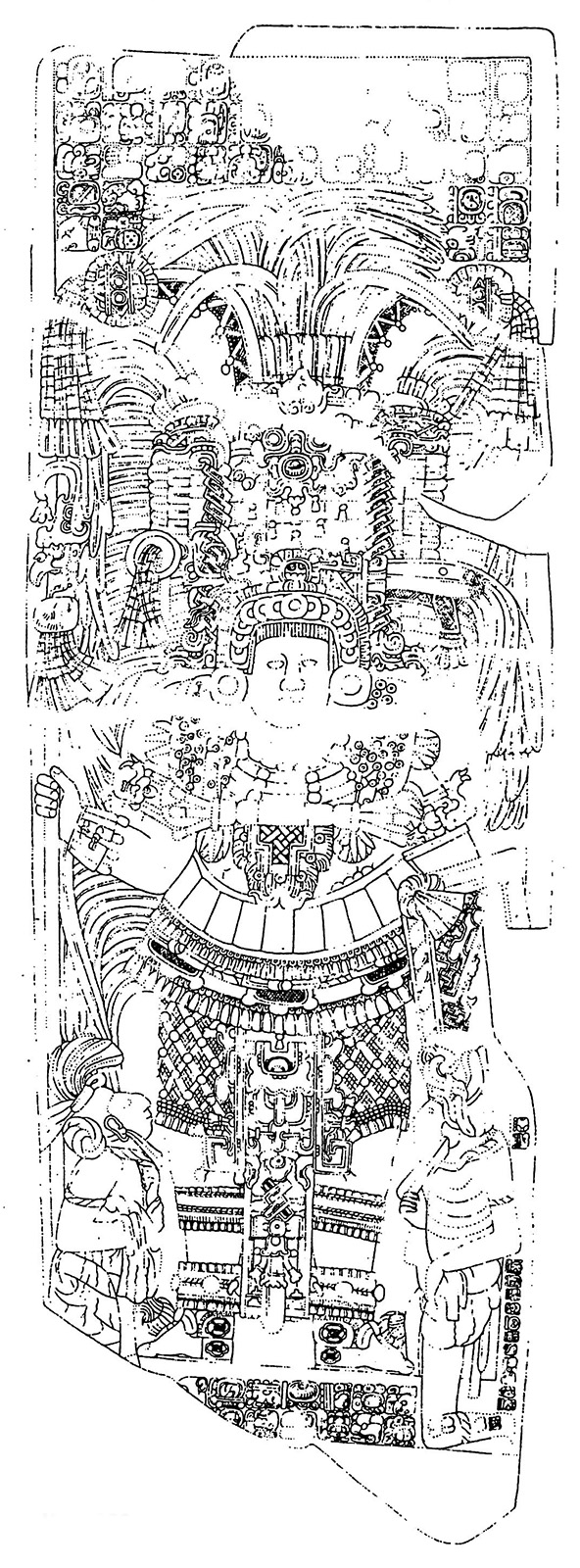

The Vase Shown Above

Above, center right, the Underworld Lord, known to scholars as “God A,” is shown dancing beside a witz “living mountain” throne, on top of which is an infant jaguar identified by its tail and paws. Art Historian Penny Janice Steinbach suggests that the infant with jaguar traits is being sacrificed as “part of a pre-accession ritual serving to endow royal heirs with the ability to conjure, which, in turn, was integral to assuming the throne.” To the right of God A is a dog, known to escort souls of the deceased across a river and into the Underworld.

Above him, is a fanciful firefly, perhaps there to illuminate the darkness of the watery world below. To the left of the spirit-spewing mountain, the rain god Chaak dances, holding aloft a hand-stone typical of those used in certain ball games and boxing matches. In his other hand, he wields an axe with which he creates lightning and thunder. Typical of Maya art, the image is filled with symbolism, glyphs and mythical references. Every element has meaning.

God A — Cizin “Farter.”

God A is a death god. He’s a skeleton figure with a distended abdomen, pronounced spinal column, truncated nose and grinning teeth. And he emits a stench, possibly that of dead bodies. He wears bell-bracelets on his hands and feet, a decapitation collar, and he has disembodied “death eyes” with the nerve stalks attached. His body is sometimes marked with “death spots,” which is a sign of decomposition. And he can be seen sitting on a throne of bones. Unlike the dance of rulers, his dance above is wild and undignified. His skeletal countenance is that of a trickster, typical for an Underworld deity.

Jaguar Rising — The Novel

The first initiation trial for One Maize to become a “man of the community” was to capture, not kill, a deer and bring it into his father’s pen alive. Here, the second of three trials is a drug-induced journey into the Underworld to see if he can hold his own with one of the Lords of Death.

Journey Into The Underworld

Excerpt From Jaguar Rising (pp. 121-123 )

Inside the temple, White Grandfather set the torch in a holder on the wall and tied back the doorway drape a little to remove the thin veil of ash that lingered in the air. Following his gesture I sat on an ocelot pelt with my back against a side wall. Painted black on the wall across from me was a medallion, a large circle with inset corners that framed the cross-eyed, shark-tooth face of Lord K’in. Taking fire from the torch with an ocoté stick, he lit some tinder in a censer. When it flamed, he added the stick and three others before setting it in front of me. He took a blue-painted calabash from under the medallion and nodded for me to take one of the many rolled-up leaves it contained. Inside the leaf was a cigar. “We wrap them with bits of copal bark,” he said, and scrapings from the backs of frogs.” It releases the ch’ulel to go through the portal.”

Sitting next to me, White Grandfather removed his headgear and re-tied the three-leaf headband so it fit snug on his forehead. After adding another stick and some copal nuggets to the censer, its sweet smoke replaced the acrid smell of burnt ash, and it wafted to a hole high in the back wall. As my eyes became accustomed to the dark, I noticed a round feather-standard leaning against the wall next to the doorway. Tied to crossed lances in front of it was a ceremonial shield with the face of a laughing falcon on it. Beside me, arranged on a reed-mat, were ceramic cups, an incense bag and an offering bowl containing strips of cotton and square leaf-packets that were tied with string and painted red. Next to my teacher was a bundle of ocoté sticks, an incense bag, a carapace drum, rattle, grinding stone and two gourds with stoppers.

White Grandfather took one of the burning sticks from the censer and lit a cigar. “This is the holy portal,” he said, puffing to get it lit. He handed it to me and told me to take several strong puffs, each time breathing it in. I’d smoked cigars with Thunder Flute and my uncles before, even inhaled, but this was very different. It was thick and tasted like a combination of tree sap and burnt thatch. The smoke stung my nose and bit my tongue. White Grandfather set the drum, rattle and incense bag in front of him. “Keep breathing it in, grandson.” I did, but I kept coughing. “Blow some smoke to the medallion,” he said pointing. “That is the place of entry, the doorway.” I noticed that it was shaped like the bottom part of a turtle shell, rounded except for inset corners. And it seemed to have been painted blue. “Fix your eyes on it,” he said, tapping the little drum with a thin white bone. Tap, tap, tap. Pause. Tap, tap, tap. On and on, always three taps and a pause. “Breathe it in, grandson…”

My teacher chanted in a whispery voice, words having to do with good sight, good happenings and good remembering. I passed him the cigar but he shook his head. “We remain behind—to guide you. Do what we ask, answer our questions as you journey along. All will become clear. There is nothing to fear.” He chanted again, louder, adding some rattle sounds in the pauses between taps on the drum. This went on so long, twice he bumped his knee against mine—hard, probably to keep me from dozing off.

“The MEDALLION IS QUIVERING, GRANDFATHER.”

“Fix your gaze on the dark center, grandson. Relax and allow yourself to go through.” The tapping stopped and I felt a damp cloth, first on my brow and then on the back of my neck. “Close your eyes now.” As I did, he tied the cloth over my eyes. Amazingly, faintly, I could still see the quivering medallion, only now it was definitely blue turning purple with blackness growing in the center. “Keep puffing, grandson. Breathe in the smoke.” More and more of the medallion was becoming black. Suddenly, I felt something in my hand. Wood. “What do you see, grandson?”

Suddenly I saw my Little Owl. “My canoe, Grandfather!” The loudness of my voice startled me. After that, I whispered. “I see Little Owl—clearly as when I painted her feathers.”

“Look around. Where are you?”

White Grandfather’s voice seemed to be coming from inside me, the sound filling me like a hollow jar. “In the canoe, in Little Owl.” What I said is not right. I am not in the canoe, I feel like I am the canoe.

“What is happening?”

“Floating—smooth—on a black river. Waterlilies all around. Maybe sky wanderers.”

Encountering Cizin Ku (The god of stench)

Excerpt From Jaguar Rising (pp. 137-138 )

Looking down from the steps and trying to clear the burning in my nose and eyes, I saw a crouched figure in the ring turning this way and that. As the smoke thinned and the water in my eyes cleared, I saw a tall, menacing skeleton with a bulbous head, crooked front teeth and a distended belly. “Cizin Ku!” I whispered. What my teacher hadn’t told me about this lord of the underworld was that the thunder farter’s presence alone was so powerful I had to tighten every muscle in my body to contain my fright. Turning his gourd-like head side-to-side, he listened and sniffed one way and another, looking for something. Or someone. Commoners on their knees backed close to the wall. In front of him, the animal companion spirits cowered and glanced up timidly. With a jerk the lord of death turned and farted a smaller thunderclap side to side, leaving them writhing in clouds of stench.

When Cizin Ku turned and looked up I stood back.

“Grandson, did you say Cizin Ku?”

His bony feet clanked on the steps and within a few terrifying heartbeats, I could smell him standing over me, his feet wreaking with sludge. Following his command, I turned to face him and backed up until I felt the cold obsidian wall of the pyramid at my back. Besides the huge and ominous eyes above his nose, he had two more eyes on the top of his head. As he turned I saw a string of them, all bloodshot and gazing at me, running down his back. He stared at me and then directed his gaze to my hand. I’d forgotten that I was holding the brush. Because it had touched the terrace, the floor was turning from black to red. His square and cavernous eye sockets had lightning cords in them, shining painfully bright.

“Go to your knees, Grandson. Bow to him. All he wants is your respect.”

I couldn’t reply, but I did what he said. The stench from the excrement on the lord’s bony feet made me gag. Bending down to face me, the mirror medallion around his neck clanked against his ribs and putrid steam issued from a slit in his bulbous, pouch-like belly. Following his command, I handed him the brush and he pressed it against his knee bone. When nothing happened, the lightning in his eyes went dark and more steam came from his belly. He drew the brush along a leg bone. Nothing. He tried again without success. A growl rumbled from within him. With the eyes on the top of his head holding my gaze and his other eyes dangling, looking around, he snapped the brush in two and hurled the pieces over his shoulder, down to the ring without turning to look.

White Grandfather kept asking me questions but I was too stunned to say anything. Also, if Cizin Ku could command me without speaking, he was probably hearing my thoughts as well. Frustrated by not making a color, he straightened to the height of two men. I saw it coming, so I covered my ears as he doubled over and expelled another deafening thunderclap. Again, it shook the chamber. High above the shiny pyramid, dust and chunks of rock broke from the ceiling and apparently fell onto the cauldron sending sparks and flakes of obsidian tinkling down the terraces and steps. Through the smoke came the sounds of agony and the odor of vomit.

I couldn’t see him, so I whispered to White Grandfather that he broke my brush. “He is angry. What should I do?”

“Offer him another one, Grandson—in your headband.”

Cizin Ku heard! As soon as I felt the cool handle slide against my scalp. He took it and pointed the bristles at my face. “Rise!” His voice bellowed inside me. I stood but kept my back to the cold wall. “Come!” He went up the steps and I followed. The lord on the fifth terrace backed away from his throne as Cizin Ku approached. The lord of death turned and said, “Make color.” I touched the brush to the seat of the throne. Red appeared and spread. He went over and pointed to the quetzal plumage streaming from the ruler’s headdress. I touched the brush to a single shaft and the blue-green color spread down and up until the entire spray became vibrant.

On the sixth terrace, the brush made the ruler’s headband white and the macaw feathers yellow and blue. On the seventh, something changed. Cizin Ku pointed to the pavement beneath his feet. When I touched my brush to it, there came a red dot but it didn’t spread. I tried to paint a circle around it and still, the color didn’t spread. I was confused, but what happened next confused me even more.

The skeleton lord stomped his foot on the dot and the color spread. The big eyes above his nose kept looking down at the color while the eyes on top of his head, worn like a headband, held my gaze. He stomped again and the color stopped spreading. Another stomp and the red spread faster than before. Much faster. Across the terrace, up and down the steps, across the other terraces. As the black pyramid was turning red the chamber fell quiet.

“Grandson, repeat our words—I am returning to the sweat lodge…” I couldn’t. I dared not to even think of it as the bony lord came close. The lightning in his eyes dimmed again. With his face close to mine, he held my gaze and asked what I had to say about his turning the pyramid red.

“With respect,” I whispered, “I must return to the sweat lodge. My teacher is calling for me.”

Cizin Ku turned and stepped away, but the long strip of eyeballs down his spine stayed fixed on me. He stomped his foot again and the colors disappeared. The pyramid, the lords, what they wore and their thrones were all drab again. The onlookers whispered their disappointment. The lord’s eyes began to brighten and he stood tall again, apparently satisfied with his display of power. Dangling Eyes, the little blue dwarf, stomped his feet and rubbed his bony arms trying to make the red come back again, but it didn’t. Inside me, I heard, tap, tap, tap.

White Grandfather’s voice became urgent, insisting that I repeat his words.

____________________________________________________________________________

For a brief description of The Path Of The Jaguar novels: Go to the Home Page—Novels

Links To Amazon.com for paperback books and Kindle Editions

Jaguar Rising: A novel of the Preclassic Maya

May the Holidays and the New Year Bring You Peace and Joy

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.

My little horse must think it queer

To stop without a farmhouse near

Between the woods and frozen lake

The darkest evening of the year.

He gives his harness bells a shake

To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound’s the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.

The woods are lovely, dark and deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

Robert Frost, Woods on a Snowy Evening

Thank you for subscribing to Ancient Maya Cultural Traits

David L. Smith

Rio Frio Cave, Belize

Rio Frio Cave, Belize